By Bonnie Bracey Sutton

By Bonnie Bracey Sutton

Editor, Policy Issues

Introduction: Parry Aftab, J.D., is the executive director of WiredSafety, a site where victims can receive one-on-one assistance when they have been bullied online. She is the author of a number of books on Internet safety, including A Parent’s Guide to the Internet (1997) and The Parent’s Guide to Protecting Your Children in Cyberspace (2000).

ETCJ: What is cyberbullying? How is it different from traditional bullying?

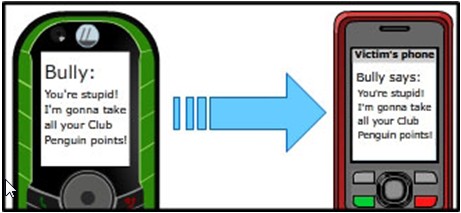

Parry Aftab: Cyberbullying is “any cyber-communication or publication posted or sent by a minor online, by instant message, e-mail, website, diary site, online profile, interactive game, handheld device, cellphone, game device, digital camera or video, webcam or use of any interactive digital device that is intended to frighten, embarrass, harass, hurt, set up, cause harm to, extort, or otherwise target another minor” (WiredSafety).

My short definition of “cyberbullying” is: “When a minor uses technology as a weapon to intentionally target and hurt another minor, it’s ‘cyberbullying’” (WiredSafety).

With one exception, all cyberbullying must be intentional. It requires that the cyberbully intends to do harm to or annoy their target. (In the one exception to this rule, the student is careless and hurts another’s feelings by accident. This is called “inadvertent cyberbullying” because the target feels victimized even if it is not the other student’s intention. Since it often leads to retaliation and traditional cyberbullying, it is considered one of the four main types of cyberbullying.)

While I am not happy with calling it “bullying,” the term seems to have caught on since Bill Belsey first coined it in Canada. In our MTV athinline.org campaign, we call it “digital abuse,” and older teens call it “drama.” (One of my Teenangels and I both serve on A Thin Line’s advisory board.) Some qualify as “digital dating abuse,” which is what we call it in the Liz Claiborne “Love Is Not Abuse” digital curriculum I developed.

Adults consider themselves victims of “cyberbullying” sometimes, but we correct their use of the term. When minors get into a fist fight, we often call it “bullying.” But when adults get into a fist fight, we call it “assault and battery.” Sadly, calling anything “bullying” somehow makes it less important. It denotes a childhood activity. So, we use it only when dealing with attacks between or among minors in cyberspace.

“Cyberbullying,” as WiredSafety defines it, needs to have minors on both sides, as target and as cyberbully. (If there aren’t minors on both sides of the communication, it is considered “cyberharassment,” not cyberbullying.) When a student harasses a teacher, it falls under cyberharassment. (Note that some new cyberbullying laws classify teacher cyberharassment as “cyberbullying” for those purposes, though.)

ETCJ: Can you give us examples of cyberbullying in school settings?

Parry Aftab: When it comes to cyberbullying, students are often motivated by anger, revenge, or frustration. Sometimes they do it for entertainment or because they are bored, have too much time on their hands and too many tech toys available to them. Many do it for laughs or to get a reaction. They may do it because they think it’s fun. A growing number do it to make a point to others, to improve their profile’s popularity or video’s page views, and get attention for their “15 megabytes of fame.”

Because their motives differ, the solutions and responses to each type of cyberbullying incident have to differ too. Unfortunately, there is no “one size fits all” when cyberbullying is concerned. We lay out what works best for each type of cyberbullying in our “What Works and What Doesn’t” and in “What Can You Do to Address It?” sections of our upcoming StopCyberbullying Toolkit (a free downloadable resource for schools).

Cyberbullying typically starts at about 7 years-of-age (younger in very connected communities) and usually ends (as “cyberbullying”) around 15. After then, the cyberharassment continues, but it changes. It usually becomes sexual harassment or is done for revenge against a former boyfriend, girlfriend, or former friend. It is often done more for titillation value than to hurt the target.

There are four types (and one sub-type) of cyberbullies. Only two of these operate both online and offline. The others are products of anonymity, impulsive technologies and lack of impulse control or digital literacy. They can only thrive online in an environment where students can be anyone they want to be or no one at all, and cybercommunications are misconveyed and misunderstood and recipients feel victimized.

The Vengeful Angel

Vengeful Angels consider themselves the Robin Hoods of cyber-space, attacking bullies to protect the victims. A Vengeful Angel often gets involved when trying to protect a friend who is being bullied or cyberbullied. They fight fire with fire and strike back against the bully. They see themselves as righting wrongs, or protecting themselves or others from the “bad guy” they are now picking on. Yet they become a bully themselves when they do this. Both girls and boys become Vengeful Angels, but more boys do it than girls. Vengeful Angels only operate in cyberspace. They do not bully offline.

Know Them When You See Them: Vengeful Angels usually act alone and don’t give away their real identity. (They might face real life bullies if they did!) They use all kinds of technology but often resort to hacking and high tech attacks. You can spot them by their messaging. They tell you that you better stop doing something or face their wrath. They often make threats like, “You better leave Clyde alone or you’ll pay!” or “If you hurt Jennie one more time, I’ll blow up your computer!”

Favorite Cyberbullying Methods: They either use direct attacks when they threaten or hack their victims or set them up by using cyberbullying-by-proxy attacks by posing as their victim and doing something to get them in trouble.

The Power-Hungry Cyberbully

Power-Hungry cyberbullies are the “thugs” of cyberspace. They want to show everyone who’s the boss and demonstrate that they are fierce enough to control others through intimidation. They are often offline tough schoolyard bullies too, just using digital technology to do their dirty work. Power-Hungry cyberbullies are all about demonstrating their power over you and want your attention. They want a reaction, and without one may try even harder to get one by increasing their threats. They are usually bigger and tougher than others in “RL” (real life) and can back up their threats. Typically they are boys, but in some cases, especially in an all-girl environment, they are girls too.

Know Them When You See Them: Power-Hungry cyberbullies usually operate alone, but they will let you know who they are because you don’t scare them. They will use any kind of technology and often make physical threats like, “I am going to punch your lights out next time I see you,” or “Next time you log in to Gears of War, you’ll see what I can do to you and your account!” They may threaten to hurt the target or someone or something they care about, e.g., “Your dog is road kill tomorrow.”

Favorite Cyberbullying Methods: Power-Hungry cyberbullies use direct attack methods, almost always. They reach out directly to their victim, and they rarely care about an audience. They send text messages, IMs, emails, and private messages to their victims. They may use high tech methods too. They can be destructive, sending malware or breaking into systems to hack, delete files or reformat drives. They think they are tough and want you to know it. They also often threaten offline acts of violence, happy to follow through (unless they are the Revenge of the Nerds subtype, see below, who can’t follow through in real life).

Revenge of the Nerds – A Subtype of the Power-Hungry Cyberbully

The Revenge of the Nerds aren’t tough in real life; they just pretend to be online. These cyberbullies are a subtype of the Power-Hungry cyberbully because they are motivated by power and getting “respect.” They like to see their victims sweat in the same way the bigger traditional Power-Hungry cyberbullies do. The only difference is that they are not big tough offline thugs who can defend themselves and throw their weight around. They are usually the ones getting bullied offline. So they always have to hide their true identity, either by anonymous attacks or posing as someone else.

Know Them When You See Them: Revenge of the Nerds cyberbullies are usually the quiet or smaller kids (they can be girls and boys, but predominantly boys unless it is an all-girl environment). Even though they can’t be real life bullies, cyberbullying is easy for them because they often have better technical skills than others. It is their intention to frighten or intimidate their victims, while never having to confront them physically or reveal their identity. They often resort to anonymous attacks or direct threats sent to their victims anonymously. Their attacks look exactly like those of the Power-Hungry cyberbully. That’s the idea. But unlike traditional Power-Hungry cyberbullies who tend to act alone, Revenge of the Nerds can sometimes act in groups with others who fit their profile. Trolling is when a group of Revenge of the Nerds cyberbullies attack together.

Favorite Cyberbullying Methods: Revenge of the Nerds cyberbullies’ favorite methods to harass others are online gaming attacks, point theft and hacking, threatening you with hacking or trying to destroy your reputation with blatantly false allegations. They sometimes target celebrities to make a name for themselves and gain attention. (Trolls are Revenge of the Nerds cyberbullies.) You might hear them say, “Hahaha! I broke into your account and stole all your gold!” or “Want to see what I can do to your music files? Watch!” They will also make threats for offline harm, even if they can’t follow through: “Your dog is road kill tomorrow

Mean Girls

They’re always mean, but not always girls. They also act in groups, with different roles for the instigator, their posses and the cyber active and passive bystanders. This type of cyberbullying occurs when the cyberbullies are bored, looking for entertainment, jealous or want to enhance their social standing. It is largely ego-based and the most immature of all cyberbullying types. Mean Girls cyberbullying is usually at least planned in a group, either virtually or together in one room. It may occur from a school library, a slumber party or from someone’s family room after school.

This kind of cyberbullying requires an audience. The cyberbullies in a Mean Girls situation want to show off their social standing and popularity and they want others to know that they have the power to cyberbully others. Posses want to show the instigator that they have her back and support her. Mean Girls bystanders fall into two categories, active bystanders who pass along messages to avoid becoming the next victim and passive bystanders who witness what is going on but do nothing to report it or stop it. This kind of cyberbullying grows when fed by group admiration, cliques or by the silence of others who stand by and let it happen. It quickly dies if the Mean Girls don’t get the entertainment value or attention they are seeking.

Know Them When You See Them: Mean Girls act in groups and usually tell you who they are. (Bystanders may not, but the instigators and their posses do.) They attack reputations and don’t deal with physical threats. They want their victims hated, ignored, socially-excluded or driven away. Their preferred methods of attack are through cell phones, text messaging, and social networks. They want to embarrass their target, and you might hear them say, “I told Becky not to bother inviting a loser like you to her birthday party.” Or they may attack a victim based on differences, passing rumors or sharing secrets. When best friends become “frenemies,” they often resort to Mean Girl tactics.

Favorite Cyberbullying Methods: Mean Girls use social technologies to get as many involved or broadcast their attacks to as many as possible. Facebook, Twitter, Formspring, text messages, IMs, and webcams are their favorite tools. They like polls of “Who’s Hot? Who’s Not?”, quizzes to make fun of their victims and photoshopping. They often use privacy intrusions and spying to capture information, passwords and pictures. What they don’t have, they will fake, pretending their victim said something they didn’t, or looked a way they hadn’t. They may use their victim’s password to pose as them and get them into trouble or embarrass them. They use indirect attack methods most often, but also use cyberbullying-by-proxy and direct threats too.

The Inadvertent or Accidental Cyberbully

Inadvertent cyberbullies usually don’t think they are cyberbullies at all. Their problem is that they are often careless and don’t think before they send out a message, so they end up hurting someone’s feelings by accident.

They also may be pretending to be tough online or role-playing. Sometimes, while experimenting in role-playing online, they may send mean messages or target someone without understanding how serious this could be. They may also do it to one of their friends, joking around. But their friend may take it seriously. Or they may be reacting to mean messages they have received. Unlike Power-Hungry or Vengeful Angel cyberbullies, they don’t lash out intentionally. They just respond without thinking about the consequences of their actions. And sometimes, they just don’t bother proof-reading their messages and a typo causes hurt feelings.

Know Them When You See Them: This cyberbully is not usually anonymous. It’s usually a friend of yours. It often doesn’t make sense. They may be joking or playing a prank. Or, maybe they were just careless and sent the message to the wrong person or left something out. They often get into trouble with typos or not explaining things well. They may have meant to send a funny message to a friend, like one gamer messaging another about their Mortal Combat: “I’m going to kill you!” But if it goes to the wrong person, they think they have just been threatened. Maybe they meant to say “Tyra is not fat!” but left out the word “not.”

They don’t have a favorite method of cyberbullying because it is accidental, not intentional. When jokes fall flat, they can do it via all digital technologies. IMs and texts may be misdirected when students zip too quickly through address books and contacts. Pranks going sour, typos that change meaning, copying the wrong people – all can lead to misunderstandings and hurt feelings by recipients.

ETCJ: What are educators doing about it and why aren’t they succeeding?

Parry Aftab: It’s impossible to change behavior when no one understands what is behind it. Cyberbullying occurs for the same reasons schoolyard bullying occurs. It also occurs by accident when students are careless about cybercommunications. It might come from impulsive and thoughtless reactions to something that has upset the “cyberbully.” They may be defending themselves and each other from offline bullies or other cyberbullies. Lumping them all together will lead nowhere, fast.

Cyberbullying starts early. WiredSafety is seeing it start as early as second grade, peaking in fourth – fifth grade, leveling off, and then peaking again in seventh and eighth grade. Part of the problem is defining it. When students hear “cyberbullying” they often think different things. Some think it means a death threat, others think it’s a fake Facebook profile set up to humiliate others. Some think it’s using lewd language or posting mean images. (You can learn more about this in “Talking the Talk” in the StopCyberbullying Toolkit.)

It starts when kids start using mobile interactive technologies, such as cellphones, DS, DSi and PSPs, and instant messaging. It continues through high school (although high school students hate admitting that they can be bullied and deny it continues through high school). It often follows their journey from technology to technology, as they develop and their interests and relationships change. The more they mature, the less they cyberbully. At the same time, if they continue as the teens get older, the cyberbullying attacks become more dangerous and better targeted to hurt their victims.

Their methods and motives change with age. Fourth graders tend to blackmail others, middle schoolers use social exclusion, and high school students tend to sexually harass their former romantic partners. This tracks their offline bullying trends, but for some reason surprises people when they look at it from the cyberspace perspective.

Anonymity plays an important role in the rapid growth of cyberbullying. More than 65% of cyberbullying occurs anonymously, by masquerading as the victim, posing as someone else or hiding all identities. This drives cyberbullying by making it harder to identify the cyberbully and allows the cyberbully to avoid having to face the real harm their actions are causing. It also emboldens students who see themselves as the “good kids” to act out by trying on the disguise of a bully, in what they consider a safe environment.

In addition to not understanding how cyberbullying works, too many bullying programs and educators trained in those programs lump cyberbullying together with schoolyard bullying. “Bullying is bullying.” But that is only half right. Two types of cyberbullies, as noted above, cyberbully and schoolyard bully, often going back and forth. Traditional Power-Hungry cyberbullies and Mean Girls operate equally in online and offline realms. But two other types of cyberbullies and the sub-type of Power-Hungry cyberbullies (Revenge of the Nerds) operate only online.

Inadvertent Cyberbullying can be avoided if the students slow down, adopt “ThinkB4uClick” practices and use emoticons. Inadvertent Cyberbullying constitutes approximately 15% of reported cyberbullying. Teaching students to “Take It Offline” and reach out to a friend who attacks them out of the blue without provocation or an argument history if something feels wrong can resolve many incidents of Inadvertent Cyberbullying as well.

Other cyberbullying is facilitated because students share their passwords with others. In WiredSafety’s surveys, 84% of grammar school students and 70% of middle and high school students have shared their password with at least one other student, often a boyfriend or girlfriend or best friend. Even when they don’t share them, their passwords are easily guessed by someone who has been in school with them for years. Middle name, pet’s name, the street they live on, favorite car, movie or rock star, the year they graduate, favorite sports team or college they want to attend are frequently used as their passwords. Armed with their secrets and passwords, classmates (especially former best friends and jilted romantic partners) can do serious damage online. They lock their targets out of their own accounts, message their friends while posing as them and violate Facebook’s terms of use while using their target’s account to get it shut down. All of this can be avoided if students are taught digital literacy skills, including how to select a password that is “easy to remember, but hard to guess,” and how to use privacy settings on Facebook and not to share their passwords or community machines without logging out between users. Easily taught and, if followed, these lessons will reduce Inadvertent Cyberbullying and many Mean Girl and Power-Hungry attacks.

Thus, without having to address courtesy and peer communication norms, teachers can eliminate another 10 – 15% of cyberbullying vulnerabilities. Sometimes just making it a little harder to infiltrate their target’s account (unless jealousy or revenge is involved) may turn the cyberbullies to the next potential target in line. By teaching the students to use anti-virus programs and firewalls, keeping them up-to-date and about common scams, malware and spyware traps, many hacking and privacy intrusion attacks of both types of Power-Hungry cyberbullies and Vengeful Angels can be avoided.

But these skills are taught in early years, if at all, and rarely touched on again. Ask any 3rd or 4th grader with a technology teacher on staff at the school to name the top four risks kids face online and along with sexual predators (or “kidnappers” as they often refer to them), “bad sites” and “cyberbullying,” they will name viruses, pop-ups and hackers. Ask them the same question in 7th grade and the malicious code sensitivity disappears.

Finally, notwithstanding the rush to add new cyberbullying laws that require schools to teach cyberbullying prevention and create policies and procedures to address cyberbullying, many teachers don’t even discuss cyberbullying. The Franklin, Mass., Teenangels chapter testified before Attorney General Coakley on February 17, 2011, in Springfield, Mass., on the new cyberbullying laws in her state. They disclosed early results of their recent survey about cyberbullying education in Franklin schools – 44% of the students surveyed said that the only time they had been taught about cyberbullying was from the Teenangels themselves. (Franklin was one of the few school districts in Massachusetts to comply on a timely basis with the new law.)

This is understandable and should be expected. Teachers aren’t trained or receive complicated and staid professional development. Offline bullying programs are smoked and mirrored to attempt to cover cyberbullying. Mandatory reporting requirements, where teachers may now face legal liability for failing to comply with often confusing and over-reaching statutes and regulations, have them caught like deer in the proverbial headlights.

How can they teach? Where are they going to find time to train while running over-sized classrooms, with mainstreamed at-risk and special needs students on reduced budgets and teaching to standardized testing at the same time? With little parent involvement or support, aging colleagues unfamiliar with the technology and schools that approach cyber-risks by locking students out of social technologies instead of embracing their potential – it’s a wonder teachers can get out of bed, much less teach cyberbullying prevention.

ETCJ: What, in your opinion, is the best solution to this problem?

Parry Aftab: The solutions are multifaceted. There is no silver bullet as our Berkman Center Internet Safety Technical Task Force report and our NTIA Online Safety Technology Working Group reports made clear. (I was a member of both.) It takes a virtual village.

Too often experts work in silos. Educators work independently from law enforcement, who work independently from social workers, mental health professionals and health professionals, who work independently from risk managers, instructional designers and technology providers. Unless or until we all work together and share what we know and our own unique perspectives, we will continue to fail.

We need to share resources and expertise. Today, while testifying at the Massachusetts cyberbullying law hearings, expert after expert said the solution to cyberbullying was information sharing. We need to do more than just share information. We have to share resources. We need to host a huge potluck cyberbullying resource dinner, with one expert bringing the standard-based mashed potatoes, and another bringing the animated messaging glazed ham. If everyone contributes what they know and have developed, from research to student empowerment programs, we can all celebrate with a feast of digital skills, peer-interaction models and normative and courteous school environment and behavior, from the crossing-guards to the bus drivers to the guidance counselors, school nurses and school administrators and teachers to students.

Experts in cyberbullying and bullying need to stop bullying each other. We in the cybersafety field could learn from this model as well. Instead of taking potshots at each other, we should stop being cyberbullies and bullies ourselves and put aside our egos and decide we have a common goal – protecting our children, encouraging safe and responsible use of digital technologies and empowering all stakeholders. We have to put the kids first.

We need to get the kids involved. My Girl Scouts’ cybersafety and cyberbullying initiative, lmk.girlscouts.org, reaches 2.5 million girls and countless site visitors of both genders, as well. My Teenangels helped me design it. Teenangels and Tweenangels are being studied by one of the leading computer science and graduate educational schools in the US for ways to expand what they learn and the programs’ effectiveness. Young people helped build AThinLine.org, together with MTV, the one network that can make cyberbullying and digital abuse prevention “kewl.” Tweenangels are advising ToysRUs on safer use of digital technologies they sell and helping build the cyberbullying resources for Verizon. Webkinz, Disney and Microsoft seek their help and insight. With the right training and supervision, young people can develop and deliver peer-to-peer resources, messaging and helplines, and better research with their help and input will help us address the problem.

The Industry leaders need to understand cyberbullying and risk management. In addition, making sure that technology and device providers know how to address cyberbullying when they encounter it and how to build safer and more private technologies that are more cyberbully-proof is essential. I advise the major players in the industry on these risk management matters and will be announcing the new Socially Safe best practices seal, shortly, to help users understand what policies and practices are behind the screen. To earn the Socially Safe Seal or the Socially Safe Kids Seal sites digital technology providers must have cyberbullying policies and procedures and their moderators and customer service personnel must be trained in handling cyberbullying and cyberharassment.

The industry must work with cyberbullying experts. Training and certification of moderation personnel, volunteers and escalation supervisory staff is being developed together with a Canadian college and with Pace University using my risk-management programs. The industry has recognized the need to work more closely with educators and safety and best practices experts. Facebook’s International Safety Advisory Board, where Facebook turns for safety and cyberbullying advice and guidance, is a primary example. Google turns to a handful of experts for help as well. We used our position with both mega-providers to create the StopCyberbullying Coalition that includes Procter & Gamble, Disney, Nickelodeon, Webkinz, Microsoft, Facebook, MySpace, AOL, Google, Verizon, LG, MiniClip, Candystand, Addicting Games, XBox, CARU, National CyberSecurity Alliance, McAfee, Seventeen Magazine, Girl Scouts, ToysRUs, Nokia, Spectorsoft, Build-a-Bear Workshop and others.

We, finally, need to provide more consistent, easily accessible and better resources to educators, without charge. Our upcoming StopCyberbullying Toolkit will do that, providing everything K-12 educators need for all stakeholders. And it will be available online. Instead of making them find room in an already over-packed semester for a new curriculum, we provide short drop-in activities tailored to each grade group, their needs and risks, that can run for 5 – 45 minutes without advance prep, using animations, quizzes, computer interactives, activity sheets, computer and board games, improv skits and student-to-student programs.

Parents have to be included, as well. Modeled after the program we developed for Singapore in 2000, the Parents Advisory Group on the Internet (“PAGI”), the WiredMoms program is growing in North America to help moms help each other guide their children’s use of digital technology. We need easy tips and advice for non-English speakers too – Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Polish, Russian and Ukranian, Arabic and Farsi. We have to keep it simple and stop expecting them to understand the technologies. We have to empower them to be parents, not their child’s best friend.

We need to share normative data. Normative information has been a cyberbullying-hyped panacea. While it will not, IMHO, work with students, it can be invaluable to parents who don’t know the norms. Students have always claimed that “all their friends” have whatever they want and don’t have. The parents of “all their friends” let them do whatever it is they want to do and aren’t currently allowed to do. In previous generations parents used to communicate and stand together opposing their children’s pleas with a knowledgeable eye. But now, no one talks to each other and parents find themselves raising their children in a vacuum. Should all 8-year-olds have a cell phone? Is Facebook okay for a ten-year-old if they are smarter than their friends? Parents need to know what makes sense and feel comfortable knowing that others are taking the same stand. Let’s bring more normative information to parents about what other parents are doing.

And, unless the students own the issue and decide to stop it themselves, all of this will continue to fail. Our Don’t Stand By, Stand Up! campaign was designed by classmates of Tyler Clementi, from Ridgewood High School in our Teenangels program. If we make it “unkewl” to cyberbully others, it will stop. If we teach them how and where to report it, and help them understand what will happen, you will see more reporting. If we make them feel safe in telling school personnel when they or others are being cyberbullied, they will tell. But, if we fail them, it all fails.

ETCJ: What are the obstacles in the way of this solution?

Parry Aftab: We don’t know enough. And those who can tell us, the students, try to hide it. We need to understand how pervasive it is, as well. We don’t.

Some very credible research has been done by trusted academic researchers. But cyberbullied students have reported to us that they hide the fact that they have been cyberbullied 95% of the time, for various reasons ranging from their doing something they weren’t allowed to do when they were targeted (such as having a Facebook page before they were allowed), parents over- and sometimes under-reacting, their not wanting to get friends into trouble or have the technologies monitored or taken away from them. They have listed almost 70 reasons they hide it, especially from their parents.

If the research is conducted with parental consent or knowledge, students tell us that they lie in their responses, hiding how often it happens. So, how can we make the findings more accurate and get students to be honest in their responses? We can get young people involved in conducting the research together with trusted academic researchers. Our new program spearheading this will be announced shortly with Pace’s Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Technology, where I have agreed to be an adjunct professor. We have been overseeing and delivering our programs to master’s and doctoral students there for three years and two are earning their PhD studying our programs’ success and findings. One is focusing entirely on our Teenangels (13-18) and Tweenangels (7-12) peer-education and leadership program.

Our Teenangels (teen peer-to-peer cybersafety experts who train up to two years for their wings under our program launched in 1999) conduct independent research as part of their training. Teens and preteens tend to be more honest with each other than they are with adults tied to parents, we have found. They also know how to define “cyberbullying” in ways their peers respond to. Depending on their particular survey (most of which were conducted with 500 or more students, typically from one school or school district), cyberbullying has been reported to affect between 50% and 80% of students responding to their surveys.

A lot has been made about our statistic of 85% of students reporting being cyberbullied. They claim that if we ignore how often cyberbullying occurs, students will somehow believe it isn’t happening and model themselves after a normative model of students being kind and courteous to their peers online and offline. I fear that this concept might work in an ivory tower, but in the classrooms educators tell us it doesn’t. All anyone has to do is talk with a middle school teacher to find out how often cyberbullying occurs and how much it disrupts school. The norm is students crossing the line, at least once in a while.

Let me explain the 85%. I visited schools around the U.S., speaking to more than 44,000 students. In each case I asked the students in the assembly if they had been cyberbullied within the last year. Instead of asking it that way, though, I outlined the kinds of activities that constitute cyberbullying and asked if they had happened to any of the students attending the presentation. Then I counted hands and did the math. No matter where I went in the U.S., I never found fewer than 85% of the students admitting that they had been cyberbullied at least once. In one case in Canada, 100% of the students at an exclusive boarding school admitted to having been cyberbullied. (I believe this may be the nature of a boarding school resident program, when students live and learn together 24/7 and have fewer outlets for their boredom.)

Does this tell us, in a peer-reviewed academically sound manner, how often students are cyberbullied? Of course not! But it tells us that students report being cyberbullied far more often than any of us would have suspected, and that while some may have said they were cyberbullied because the group did, many feel cyberbullied. Far more than should.

To understand how pervasive cyberbullying is, we have to find a way to engage the students to share with us. If you don’t know how students define it, you will never get to the solutions. It’s a matter of speaking their language. (Don’t be tempted to use text or chat lingo terms if the students are in eighth grade or older. It’s something used by younger students, except as shorthand for texting.)

The ways they cyberbully are becoming more sophisticated as well. SIM cards are the new favorite of cyberbullies who swap them, erase them and reprogram them. I was at a high school in New York recently and asked the students to list various ways they cyberbully each other. One young man, a leader in his class and a great kid, offered that a student would grab an unattended cellphone and reprogram the victim’s best friend’s or romantic interest’s number to their cell number. When they sent a mean text message, it would come up as the best friend or girlfriend or boyfriend instead of theirs and the victim would blame their friend and be doubly hurt. (They should spend half the time studying as they do dreaming up these kinds of schemes!)

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges of all is how very smart and educated people misunderstand the cyberbullying dynamic. Students who are victims of offline bullies often turn the tables by becoming online bullies, and not only to get even. They enjoy the feeling of power. They like to see the big guys and popular girls sweat.

Good kids think that what they are doing online is just harmless fun, without realizing how others are affected. Students tired of watching others rule the schoolyard bullying roost step up, anonymously and viciously, online. Students who would never join in in RL pass along rumors and secrets happily using cellphones, Facebook and IMs. Third graders send lewd hand drawn pics using their Nintendo DS and DSi Picto-Chat features.

Cyberbullying goes farther than many offline bullying attacks, without the fear of detection, consequences or adult witnesses. And it often is conducted alone, in quiet seclusion, without anyone to warn them they have gone too far.

Impulse control creates serious problems for students with more power in their backpacks, pockets and purses than large corporations had a decade ago. The technology is so accessible and the opportunity so enticing that what they normally don’t say out loud, they are willing to express online. And they share far more than they should, which makes them vulnerable to cyberbullies and privacy invasions. Different profiles, different motives and different methods attract different students, both as the cyberbully and often as the target.

Closet bigots are more comfortable sniping anonymously. And hate sites and groups are online and active just as all other groups. Students are now posing as their targets and challenging gang members to fights in the guise of their targets, resulting in physical assaults. They are posing in the nude from the neck down, claiming to be a similarly-endowed target and soliciting sexual encounters in their name. Well-liked and personable students are attacked, anonymously, by those jealous of their popularity. This kind of an attack would never be tolerated in real life.

The impersonation potential of digital technology allows students who normally color within the lines to act out in ways they would never do in real life.

ETCJ: Why are you personally interested in this problem?

Parry Aftab: My interest in cybersafety came from three directions:

- I was one of the first “cyberlawyers” in the world and specialized in cyber-privacy and security law. Safety is a natural offshoot of privacy and security.

- I was sent a link to a website, asking me to have it shut down and the people behind it jailed. It turned out to be a child pornography site and I saw an image of a little 3-1/2 yr old girl being raped. I vowed to find her and help others like her.

- And, I too believed in Martin Luther King’s dream of children being judged on the quality of their character, not the color of their skin, the size or cost of their jeans, how they worship or their accent.

The road to that is empowerment of young people. Too many others thought the only way to keep students safe was to keep them in the dark silent analogue world. I thought that was short-sighted. The greatest single risk, I believe, is children being denied access to the tools they need for education, careers and their role in a worldwide community. We have solutions for everything else. It just requires us to think outside of the box and park our egos at the door.

I sold my house, cashed in my retirement and emptied my savings to fund and form the charity that I volunteer my time running. I didn’t think I had a choice and believe the same thing now. If you are lucky enough to be in a position to help guide young people into the future, a better and hopefully more enlightened future, you are very lucky indeed. Teachers understand this better than most.

The Internet offers promise to those without promising futures. Those in rural communities can access resources in wealthy urban communities. Virtual tourism, being able to reach famous and talented mentors and seeking creative options to everyday experiences are all within reach, if our students know how to use and have access to digital technologies. Online, all children can walk, talk and see. They are judged, as Dr. King hoped, on the basis of their character online. Unless they post photos, videos or engage in webcam chats, no one is too fat, or too tall or too whatever.

But cyberbullying kills all that. It takes the wonder of the Internet and turns it into an arsenal of weapons designed to hurt others. One of my Teenangels told me, at the age of thirteen, that she was more hurt that her former best friend took so much time and effort just to hurt her online. “Cyberbullying hurts your heart,” she told me.

There are enough ways our children’s hearts will be hurt over the years. But the power of the Internet to reach them 24/7, in their favorite online places, at grandma’s house, school or the mall, getting inside their safe places no matter who is around, is being abused and misused to do it. It’s not fair. It is cruel. It has driven some students to self-harm and even suicide. It is done as casual entertainment. And it has to stop.

Unless we can make the technology safer and provide the right skills to use it responsibly and teach cyber-self-defense, we can’t expect students to use it, enjoy it or benefit from it. We owe it to the kids.

ETCJ: Tell us a little about your professional background. Do you have a link to a website with a bio and photo?

Parry Aftab: Aftab.com is my personal website, and WiredSafety’s main cyberbullying website is stopcyberbullying.org. The upcoming StopCyberbullying Toolkit will be distributed by our partners and on our sites, without charge, to schools and community organizations. WiredSafety is a charity where all of us volunteer our services without charge. We live around the world and operate virtually, wherever our computers, smartphones and mobile devices are situated. We have one goal – helping everyone become empowered to use digital technology in productive and fun ways, safely.

ETCJ: Is there anything else you’d like to share with us?

Parry Aftab: I am the cyberbullying and cybersafety contributor for both the Today Show and Good Morning America and a regular on CNN, MSNBC and Dr Phil, among others. I appear often as an expert in print news and magazine publications. I was fortunate to have been included as one of 150 experts brought to Washington by Arne Duncan and Kevin Jennings for the first Federal Bullying and Cyberbullying Summit.

In 1996 I wrote the first Internet safety book for parents, A Parents Guide to the Internet, which was released in 1997. I have written other cyberbullying and cybersafety guides around the world since then. The FBI is presenting me with the Directors Community Leadership this year and I have received many other prestigious awards over the years.

The first front page article for the New York Times on cyberbullying was written in 2004 by Amy Harmon, after accompanying me to student presentations to learn what kids and teens had to say. I speak to 8-10,000 students most months and up to 2,000 parents. I have been doing this longer than most others and have been included in every major initiative and task force appointed to review these issues.

Why am I sharing this with you? Because no matter how often others and I appear on TV, in the news or in print publications, no matter how many books we write or children and parents we address, no matter how many awards and commendations we receive, we are failing.

Too few teachers, school administrators, industry leaders, law enforcement, judges and prosecutors, parents, healthcare and mental health professionals and other important stakeholders know the basics. They may know some buzz words, but don’t know how to report abuse and where to report it. They don’t know what to do when something hurts them or others online. They are bystanders and stand paralyzed, without the skills to help themselves or others.

Too few know about the great work so many are doing, valuable and free resources and programs that are effective. They function alone, thinking that they have to reinvent the wheel. Unless we can change this, all of us will fail – we will fail our children. Shame on us!

School’s Legal Authority and Obligations in Off-Campus and After-Hours Cyberbullying. In addition, over the next few years we should expect a few new legal developments putting more obligations on schools for enforcement of the range of laws that cover cyberbullying actions.

When a school disciplines a student for creating a website or profile, posting a message online, or sending a digital communication (text messaging, instant message, e-mail, etc.) off school grounds and outside school hours, it is treading on very dangerous legal ground.

The websites and messages vary from school/administration/teacher/student bashing, to cyberbullying and harassment of fellow students or teachers, to fights being broadcast online on MySpace or YouTube to sending vulgarities and threats, to encouraging others to hurt or kill someone, or threatening to do it yourself. Sometimes the students are just behaving badly, or are rude and hurtful, and sometimes they are committing serious crimes, including hacking, identity theft, vandalism, assault and battery, and targeting victims for attacks by hate groups and predators.

In the United States, cases have challenged the school’s authority in many states and federal jurisdictions under Constitutional and procedural grounds. Although the decisions conflict, there is some guidance from the U.S. Supreme Court on free speech issues in schools and schools have been given more leeway recently. The last definitive line of cases was largely decided during the Vietnam War. A recent Supreme Court case has given some vague guidance, but nothing definitive; a 2009 case ruled that peer-to-peer sexual harassment is covered by existing educational civil rights laws and a line of off-premise jurisdictional cases is moving towards the Supreme Court that may help clarify this issue once and for all.

Most other issues will continue to be resolved by lower courts and the law will vary depending on the state or federal district or circuit in which the school is located. So, before taking action, it is essential that the school district seeks advice from knowledgeable counsel in this field. The normal school district lawyer may not have the requisite level of expertise to advise on this, and a Constitutional or cyberlawyer may have to be retained.

There are a few generalizations we can provide which can give some general guidance. However, these cases are very fact-specific and the facts in your case may differ from those in the cases already determined in your jurisdiction.

- Clear threats: If there is a clear-cut threat (one that is seen by both the person making the threat and those who have seen it or received it), the school is generally entitled to take action, including suspension and expulsion.

- Clearly disruptive of school discipline: If the school had proof that the speech has or will disrupt school discipline, the school has a better chance of succeeding. Ungrounded fear or speculation is not sufficient to support the school’s burden.

- In-school activities: If the student is bringing in print-outs of the website, or promoting other students in school to visit the site, text-messaging during school hours, or if the student accesses the website while at school or creates or works on the website from school, there is a greater likelihood that the actions will not be deemed out-of-school activities and would fall within the school’s authority.

- School-sponsored activities: If the website belongs to the school or is created as a school-sponsored project, it will probably fall under existing U.S. Supreme Court decisions permitting school authority. (A school group on Facebook created by students would not qualify here.)

- On-premises activities: If a student targets another student using interactive technologies or the Internet, there is almost always an in-school activity related to the cyberbullying. Privacy-invading e-mails and harassing messages are often printed out and distributed in school and on school grounds. In addition, cyberbullying typically creates a disruption in school; the victims are afraid, may seek counseling or miss school, their grades may be impacted, and friends may get involved. Any proof of an in-school student impact will help support a finding of school authority. You should note, however, that some courts have not extended the school’s authority to offline and off-premises actions in a cyberbullying case when the cyberbully himself did not bring the printed materials into the school. Others doing it may not be attributable to the cyberbully, without independent action and intent.

- Cyber staff harassment: If the school can demonstrate that the student’s website or harassment has had a real impact on the staff, the school has a greater likelihood of success in upholding its authority. If the teacher or staff member quits in reaction to the harassment or takes a leave of absence or seeks medical treatment to help deal with the emotional implications of the student’s actions, the courts tend to be more sympathetic and are more likely to give the school the authority to discipline the student. Without this, the courts tend to lean towards leaving the staff member to other legal recourse.

Schools are also attacked (often successfully) when they fail to follow their own procedures. Sometimes pressured by angry staff members, parents, and fear of the problem growing out of control, they fail to adhere to their own written rules. They fail to give the requisite notice, in the requisite manner, and allow the requisite response period to lapse before calling a hearing. They sometimes fail to notify the parents and give the student’s family a chance to respond. This is not a time for shortcuts or acting without careful planning.

Sometime the schools over-reach in their policy, attempting to prohibit speech too broadly. These policies are generally knocked down unless the school can demonstrate a practice that limits an overbroad reach and clarifies what is prohibited and what isn’t for the purposes of the policy and school rules. One school even reserved the right to examine any home computer of their students to determine whether a cybercrime or abuse has taken place using that computer.

The schools have a valid concern and legal obligation to maintain discipline and protect students while in their care. But in this tricky area, especially when damages for infringing on the students’ rights can exceed the annual salary of much-needed teachers and other educational resources, schools cannot afford to guess. Until the law becomes better settled, or unless a local cyberbullying law giving schools extended authority exists in their jurisdiction, the schools need to be careful before acting, seek knowledgeable legal counsel, plan ahead, and get parents involved early.

ETCJ: Parry, thank you very much for taking time out of your very busy schedule to talk with us.

__________

Parry Aftab is a child advocate and has been working on cyberbullying and cyberharassment cases since 1995. She is an Internet privacy and security lawyer and runs StopCyberbullying.org, a goldmine of information and resources on cyberbullying. Visit her web site: http://www.aftab.com/

Filed under: Uncategorized |

John Mark Walker: "If educational communities can continue to push platform integration and content portability, in the future, students may be able to design their own personalized degrees from smaller, modular chunks that cross institutional barriers" (

John Mark Walker: "If educational communities can continue to push platform integration and content portability, in the future, students may be able to design their own personalized degrees from smaller, modular chunks that cross institutional barriers" ( Richard Koubek

Richard Koubek

Judith McDaniel

Judith McDaniel Tim Fraser-Bumatay: "Although the format leaves us far-removed physically, the online forum has its own sense of intimacy" (Judith McDaniel, "

Tim Fraser-Bumatay: "Although the format leaves us far-removed physically, the online forum has its own sense of intimacy" (Judith McDaniel, " Ryan Kelly: "For me to be able to work with people clear across the country for an extended period of time opened me up to new things" (Judith McDaniel, "

Ryan Kelly: "For me to be able to work with people clear across the country for an extended period of time opened me up to new things" (Judith McDaniel, " Daniel Herrera: "As a Mexican American, I know that words of identity are powerful; so to discuss white privilege with my professor and classmates in a face-to-face class would have been terrifying and impossible" (Judith McDaniel, "

Daniel Herrera: "As a Mexican American, I know that words of identity are powerful; so to discuss white privilege with my professor and classmates in a face-to-face class would have been terrifying and impossible" (Judith McDaniel, "

Cathy Gunn: "Traditional methods for effecting change at my institution aren’t getting us even to a trickle yet, let alone to thinking about or planning for a wave!" (

Cathy Gunn: "Traditional methods for effecting change at my institution aren’t getting us even to a trickle yet, let alone to thinking about or planning for a wave!" (

[…] Cyberbullying: An Interview with Parry Aftab Posted on February 17, 2011 by admin […]

[…] https://etcjournal.com/2011/02/17/7299/ […]

[…] é uma paixão minha e foi antes de Nancy Willard ou Parry Aftab entrou nas discussões, mas congratulo-me com toda a ajuda que as crianças precisam. Eu era uma […]

[…] Ceux qui font l’objet de moqueries voire de harcèlement hors ligne et qui se servent de leurs connaissances informatiques pour se venger de leurs harceleurs ; l’avocate américaine Parry Aftab (spécialite du droit numérique) appelle ce phénomène la « revenge of nerds » ; […]