By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

(Also see Oregon Trail: Fletchers Settle in Tualatin Valley, Algorithm of an Intentional Heart, The AGI Among Us, Close to You, Tea With Bachan: An Alien Lesson.)

Introduction: Yesterday, Claude and I collaborated* on a short story, told by Claude from the perspective of a twelve-year-old boy who is traveling the Oregon Trail in a wagon train in 1848. -js

My name’s Thomas Fletcher, but most folks just call me Tommy. Pa says I’m small for twelve, but I reckon I’m doing a man’s work out here, so that’s got to count for something.

We been on this trail near two months now, left Independence back in April when the grass was just starting to green up good for the oxen – though we got mules, not oxen. Pa says mules are steadier, don’t spook as easy. Every morning I’m up before dawn helping Pa check the harnesses and loading our gear back in the wagon. Ma and my sister Sarah, she’s fourteen, they pack up the cooking things and whatever we pulled out for sleeping.

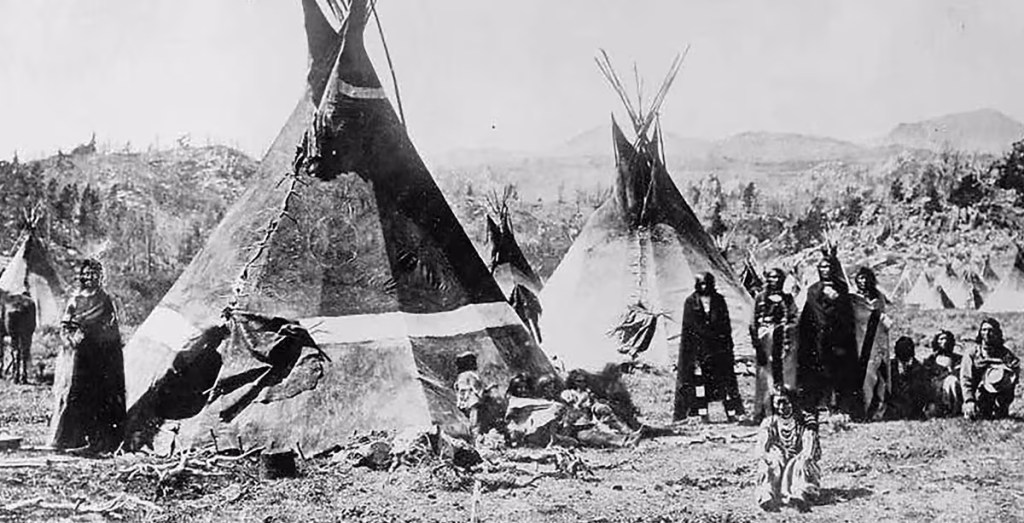

I carry Pa’s old musket. This here’s a .50 caliber percussion cap musket, heavy as anything, and Pa showed me how to load and prime it proper. Haven’t had to use it yet, but we seen Indian sign twice now. Captain Morrison, he’s our wagon master, says the Pawnee in these parts ain’t usually looking for trouble, but a man’s got to be ready.

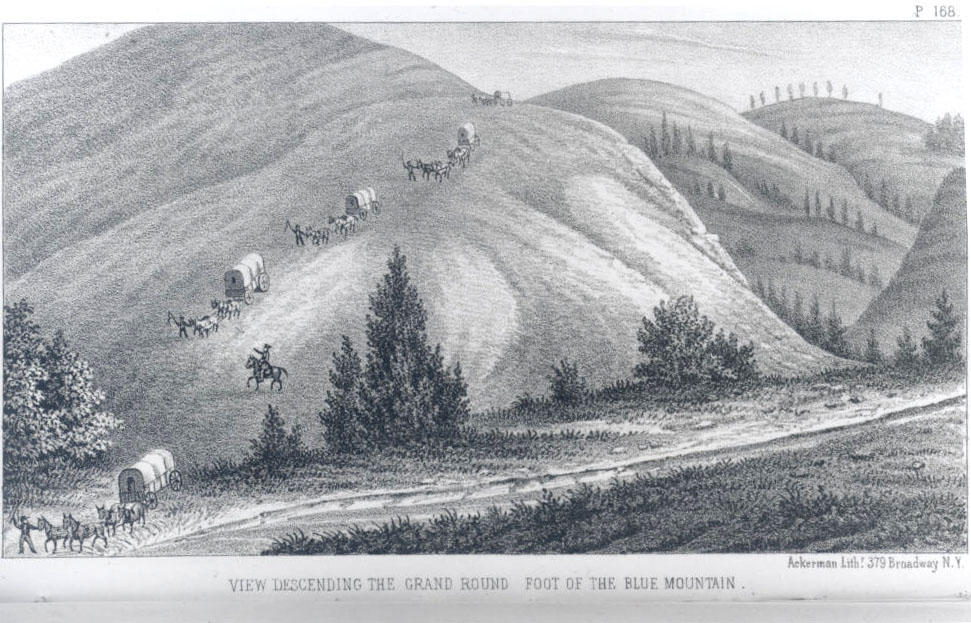

Walking all day beside that wagon, my feet are tough as leather now. Sarah and me, we take turns scouting ahead for the best ground, looking for prairie dog holes that could break a wheel or lame a mule. My job’s to watch the sides mostly, keep an eye out for anything that don’t look right. Pa taught me to read the land – where the grass grows different, where animals been through, how to spot water from a distance.

The dust gets in everything. Everything. Ma tries to keep it out of the food, but we’re always crunching grit between our teeth. Water’s the hardest part – we got to make every drop count between rivers, and some of them rivers… well, they ain’t fit for drinking even when you can find them.

At night, after we circle the wagons, I help Pa tend the animals and gather buffalo chips for the fire. Sarah helps Ma with supper – usually beans and salt pork, maybe some hardtack if we’re lucky. Then I got to clean that musket and check my powder’s dry.

I miss our farm back in Missouri something fierce, especially my dog Rex. Had to leave him with Uncle Henry. But Pa says there’s good land out in Oregon, free land, and a man can make something of himself there. I just hope we all make it there together.

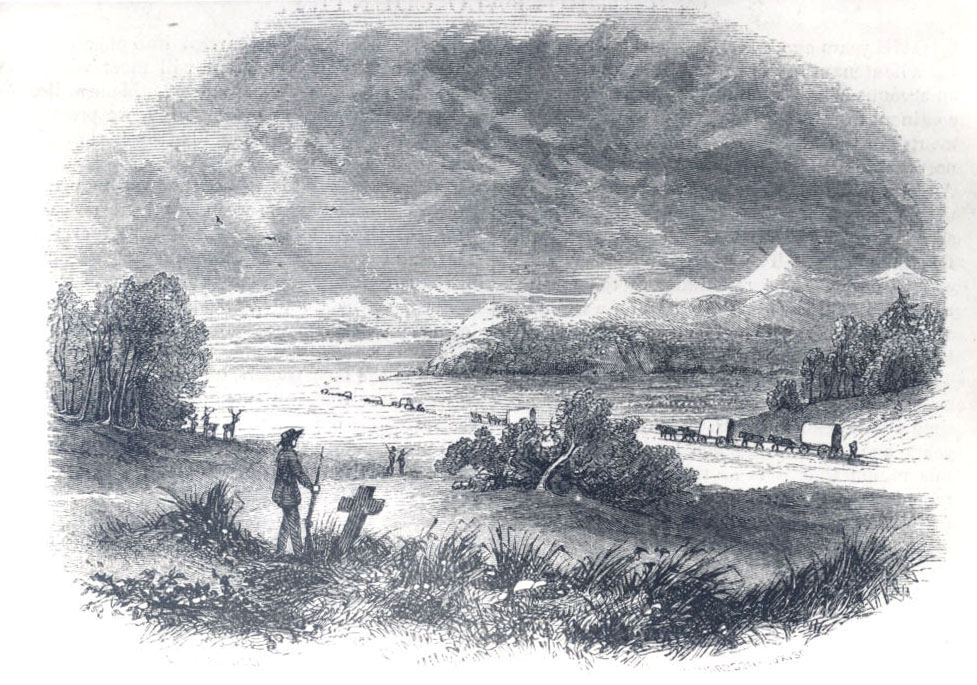

The hardest part ain’t the walking or the work – it’s when little ones in the other wagons take sick, or when we had to bury old Mr. Patterson back at Ash Hollow. Makes you think about things a boy shouldn’t have to think about, I reckon.

Well, that was something that happened about three weeks back, and I still think about it near every day.

Me and Johnny Walsh – he’s thirteen and travels with the wagon just ahead of ours – we been wanting to try our hand at real hunting. All we ever got to shoot at was prairie hens and jackrabbits close to camp. But Captain Morrison, he’s real strict about nobody wandering off more than a rifle shot from the train.

This one afternoon though, we spotted a small herd of antelope maybe two miles north, and Johnny, he convinced me we could bag one and be back before anybody missed us. We told our pas we were going to scout for firewood, and we slipped off when the train stopped for the noon rest.

We followed a little creek bed, figuring the antelope would come to water. Found this sweet little spring tucked back in some rocks, clearest water I ever seen. We were filling our canteens and figuring how to get close to them antelope when we heard a splash.

There was this Indian boy, couldn’t have been much older than me, maybe Johnny’s age. He was crouched by the spring, and he had these two rabbits he’d caught. Soon as he saw us, he froze up like a deer in lantern light. We all three just stared at each other for the longest time.

Johnny, he raised his musket partway, but something in that boy’s face… he looked scared, but not mean scared. Just… surprised, like we were. He had on buckskin leggings and his hair was braided with some kind of beads. Real thin, like maybe he hadn’t been eating regular.

I don’t know what came over me, but I set my rifle down and pulled out a piece of hardtack from my pocket. Held it out to him. Johnny hissed at me like I’d gone plumb crazy, but that Indian boy, he looked at that hardtack like it was gold.

We couldn’t talk to each other proper, but we sat there by that spring for maybe twenty minutes. He showed us how he’d caught them rabbits with just some twisted grass and a snare. Smart as anything. When we heard the wagon train’s horn blowing in the distance, we knew we had to get back.

That boy, he pointed west, same direction we were heading, and then he pointed at himself. Made me wonder if maybe his people were traveling too, just trying to get by same as us.

Johnny made me promise not to tell nobody about it. Said Captain Morrison would have our hides, and he’d probably organize a scouting party thinking there was a war party nearby. But that boy didn’t look like no warrior to me. Just looked… lonesome, I guess.

Still think about him sometimes when I’m walking beside the wagon. Wonder if we’ll see him again, or if his people are hungry too. Makes a fellow think that maybe we ain’t so different, just trying to find our way in all this big empty country.

That very same evening, just as we were settling in for supper, Mr. Henderson came riding back hard into camp. His horse was all lathered up and he was hollering before he even got off.

“Captain Morrison! Indians! About three miles ahead!”

The whole camp just went dead quiet for a second, then everybody started talking at once. Ma grabbed Sarah close, and I seen Mrs. Peterson start crying. Little Billy Morrison, the Captain’s youngest, he started wailing something fierce.

Mr. Henderson, he was breathing hard, said he seen smoke rising from behind some rocks near the river. Snuck up close and counted maybe three or four Indians around a small fire. Had some kind of shelter set up, looked like they been there a day or two.

Pa’s face went real serious. He pulled me aside and checked my musket, made sure I had my powder horn full. “Tommy,” he says, “you stay close to the wagon tonight. Real close.”

Captain Morrison called all the men together for council. I could hear them arguing – some wanted to circle up right there and wait it out, others said we should send a party to parley, see what they wanted. Mr. Schmidt, he lost his brother to Indians back in Kansas, he was all for loading up every gun we had and driving them off.

Johnny found me after the men broke up their talk. He looked white as a sheet. “Tommy,” he whispered, “you don’t think… you don’t think that boy we saw…”

My stomach just dropped right out of me. What if that lonesome boy I shared my hardtack with was part of that camp? What if by being kind to him, I’d somehow put the whole train in danger? What if they’d been watching us all along?

The women gathered up all the children in the center wagons. Sarah and me, we were old enough to stand watch with the men. All night long we kept them fires burning bright, and every little sound – an owl hooting, a coyote calling, even the mules shifting around – had us all jumping.

I kept thinking about that boy by the spring. Was he hungry because his people were running low on food too? Were they planning to raid us, or were they just trying to get by, same as us?

Didn’t sleep a wink that whole night. Just kept staring out into the darkness, wondering if tomorrow we’d be fighting, or if maybe, just maybe, we’d find out they were just folks trying to make their way through this hard country, same as we were.

But I couldn’t tell nobody about what me and Johnny seen. Not with everybody so scared. Sometimes doing the right thing and keeping folks safe don’t line up the way you’d hope they would.

I near jumped clean out of my skin when that pebble hit me. Johnny, he spun around so fast he almost dropped his musket. We both peered out into the darkness beyond our little circle of firelight, hearts pounding like war drums.

At first we couldn’t see nothing. Then, real slow-like, a shadow moved near that big cottonwood maybe thirty yards out. Johnny raised his gun, but I put my hand on his arm. Something about the way that shadow moved… it was small, careful, not trying to sneak up on us exactly, more like… like it was trying not to spook us.

Then I seen him step just a little into the moonlight. It was that boy from the spring. Same buckskin leggings, same thin frame. He was alone, and he had his hands up a little, showing he wasn’t carrying no weapons.

“Sweet Jesus,” Johnny whispered. “What’s he want?”

The boy pointed at me, then at himself, then made this motion toward the darkness – like he wanted me to come talk to him. My mouth went dry as dust. Here was Captain Morrison telling everybody to stay calm, that these Indians weren’t looking for trouble, and now one of them was calling me out into the dark.

But looking at that boy’s face in the pale moonlight, I didn’t see no meanness there. Same look he’d had at the spring – careful, maybe a little scared, but not angry.

“Tommy, don’t you even think about it,” Johnny hissed. “You step one foot outside this camp and you’re gonna get us all killed.”

But I kept thinking about how hungry that boy had looked, how he’d showed us that rabbit snare. And Captain Morrison’s words – this wasn’t no war party. Maybe… maybe this boy had something important to tell us.

The boy took another step back, still keeping his hands visible, still looking right at me. Then he did something that made my heart skip – he pulled out a piece of that hardtack I’d given him, held it up so I could see it, then pointed west again, just like he’d done at the spring.

Johnny grabbed my arm. “Tommy Fletcher, if you take one step toward that Indian, I’m gonna holler for your pa right now.”

I was torn something fierce. Every sensible part of me knew Johnny was right. But something else, something I couldn’t quite name, was telling me that boy had come here for a reason, and it wasn’t to hurt nobody.

The question was – was I brave enough to find out what that reason was, or fool enough to get us all in trouble trying?

I looked Johnny square in the eye and said, “I’m going. That boy’s trying to tell us something important, I can feel it. You can trust me on this.”

Johnny shook his head real slow. “Tommy Fletcher, you’re gonna be the death of both of us.” But then he sighed and hefted his musket. “Well, I ain’t letting you go alone. If we’re gonna get scalped, least we’ll get scalped together.”

We set our guns down real careful against the wagon wheel – didn’t want that boy thinking we were coming to fight. Then we started walking, real slow and quiet, toward where he was standing. Every step felt like it took forever, and I kept expecting to hear Pa or Captain Morrison hollering at us to get back.

The Indian boy watched us coming, and when we got maybe ten feet away, he held up his hand for us to stop. Up close, I could see he was breathing hard, like he’d been running. His eyes kept darting back toward the darkness behind him, then back to us.

He pointed at himself and said something in his language – sounded like “Aiyana” or something close to that. Then he pointed west again, same as before, but this time he made these motions with his hands, like water flowing, then he pointed down at the ground and shook his head real worried-like.

Johnny whispered, “What’s he trying to say?”

The boy seemed to understand we weren’t getting it. He knelt down and started drawing in the dirt with his finger. First he drew what looked like our wagon train – little circles in a line. Then he drew squiggly lines ahead of us, and made this real serious face. He pointed at the squiggly lines, then made a motion like something big and dangerous.

Then it hit me like a thunderbolt. “Johnny,” I whispered, “I think he’s trying to warn us about something. Something up ahead on the trail.”

The boy nodded real eager when he seen I was starting to understand. He kept pointing west, making that worried face, then he’d point back at our wagon train and shake his head.

Whatever was out there, this boy had come alone in the dark, risking getting shot by our guards, just to warn us about it.

Once Aiyana got us to understand about the river danger, he started telling us more, using his hands and drawing in the dirt. Johnny and me, we pieced it together bit by bit.

He drew his little group again – just a few people, not many. Then he made these motions like riding horses, heading toward them squiggly water lines. He acted out crossing – made his fingers like a horse and rider, then suddenly his hand jerked and tumbled, like something got swept away.

When he pointed to himself and then made a real sad face, then drew a bigger man in the dirt… that’s when I understood. His pa got hurt bad trying to cross that river.

Aiyana rolled up his buckskin legging and showed us this long cut on his own leg, already healing up. He’d been hurt too. Then he made motions like people lifting, carrying – his tribe helping them. But then he pointed to his drawn-out pa and shook his head, like his father couldn’t travel yet.

He swept away most of the little circles he’d drawn for his people, showing them moving on. Left just three little marks – him, his pa, and I reckon his ma. The others had to keep going, looking for game, looking for a safer place to cross. But they’d left signs.

Aiyana showed us how – he broke a small branch and stuck it in the ground pointing northwest. Then he picked up some stones and arranged them in a little arrow. That’s how his people would know which way to go when his pa got strong enough to travel.

“So that’s why he was alone at the spring,” Johnny whispered. “His family’s waiting for his pa to heal up.”

The boy nodded real serious when he heard Johnny say “pa” – seemed like he understood that word. Then he pointed at our wagon train again and made that worried face, shaking his head real firm. He drew the river again, made it look all angry and dangerous.

That boy had risked everything – walking into our camp where he could’ve been shot – just to warn us about something that had already hurt his own family. His pa was laid up somewhere nearby, probably in pain, and here was this boy thinking more about keeping us safe than about his own troubles.

I felt ashamed, thinking about how scared we’d all been earlier. This wasn’t no war party planning to raid us. This was a family broke apart by bad luck and a dangerous river, and this brave boy was trying to keep the same thing from happening to us.

We looked at each other, and Johnny nodded. “We got to tell Captain Morrison,” he said. “This is bigger than us getting in trouble.”

So we motioned for Aiyana to wait, and we crept back to camp quiet as we could. Found Captain Morrison sitting by the dying fire, cleaning his rifle. When we walked up, he looked at us real stern.

“Boys, what are you doing away from your posts?”

“Captain Morrison, sir,” I said, my voice shaking a little, “we got something real important to tell you, but we… we might’ve done something we weren’t supposed to.”

His eyebrows went up, but he set down his rifle and gave us his full attention.

So we told him everything. About sneaking off to hunt them antelope. About finding Aiyana at the spring. About sharing my hardtack. About tonight, when the pebble hit my head, and how we went out to talk to him.

Captain Morrison’s face got darker and darker as we talked, especially about us leaving the wagon train without permission. But when we got to the part about Aiyana warning us about the river, he leaned forward real sharp.

“You’re telling me this Indian boy came into our camp, alone, just to warn us about a dangerous crossing?”

“Yes sir,” Johnny said. “His own pa got hurt bad trying to cross it. Their people had to leave them behind. He drew it all out for us in the dirt.”

Captain Morrison was quiet for a long moment, looking out toward where we’d left Aiyana waiting. “And this boy… he’s still out there?”

“Yes sir. We told him to wait.”

The Captain stood up slow. “Boys, what you did leaving the train was dangerous and foolish. We’ll talk about that tomorrow.” His voice got softer. “But what you’re telling me now… if this boy’s speaking truth about that river, he might’ve just saved lives.”

He looked toward the darkness. “Think he’d talk to me? Show me what he showed you?”

I nodded. “I think so, sir. He seemed real worried about us heading into danger.”

Captain Morrison picked up his rifle, not threatening-like, just careful. “Well then. Let’s go meet this young man who’s trying to keep us all from drowning.”

Captain Morrison, he understood right quick what Aiyana was trying to tell us. When that boy drew out the river crossing again and showed how his pa got swept under, the Captain’s face went real serious. He’d seen plenty of river crossings go bad in his years leading wagon trains.

“This boy might’ve just saved us from losing wagons, maybe even lives,” he said quiet-like.

Then the Captain did something that surprised me. He told us to gather up some supplies – salt pork, beans, hardtack, even some of the precious coffee beans. “If this family’s been waiting for the father to heal, they’re probably running low on food,” he said.

When he asked Ma about going to tend to Aiyana’s pa, her eyes just lit up. “Of course I’ll go,” she said, already gathering her medicine bag. “A man with injuries needs proper care.”

Ma had helped birth three babies on the trail already, and she’d doctored plenty of cuts, fevers, and such. Folks had started coming to her first before bothering with their own remedies.

So there we were – me and Johnny with packs full of food, Ma with her medicine bag, and Aiyana leading us through the darkness. Captain Morrison sent two of the men to follow at a distance, just to be safe, but he told them to stay back unless there was trouble.

Aiyana’s camp was tucked back in some rocks near a little creek, maybe half a mile from where we’d made our circle. As we got close, I could see the glow of a small fire, kept real low. A woman’s voice called out soft in their language, and Aiyana answered back.

When we stepped into the firelight, I seen Aiyana’s ma for the first time – a thin woman with worry lines around her eyes, but she had the same gentle look as her son. And there was his pa, lying on a buffalo hide, his leg all wrapped up with strips of hide and what looked like moss or some kind of plant.

Ma went right to work, unwrapping that leg real gentle. The man’s eyes were bright with fever, but when Ma started cleaning the wound with water from her own canteen, he seemed to understand she was there to help.

“This is bad,” Ma whispered to me, “but it’s not past fixing. Just needs proper cleaning and fresh bandages.”

Watching Ma work on Aiyana’s pa, and seeing the grateful look in that woman’s eyes when we unpacked all that food… well, it made me think maybe folks ain’t so different after all, no matter what they look like or what language they speak. We all just want our families to be safe and fed and healthy.

When we got back to camp that night, Ma went straight to Captain Morrison. I could hear her talking real serious-like about Aiyana’s pa – how the wound was deep but clean, how the fever meant it was fighting infection, but how moving him too soon could make things worse.

“That man shouldn’t be walking for at least another week,” she told the Captain. “But if we could carry him in a wagon…”

Captain Morrison nodded slow, then called for a meeting with the senior men – Pa, Mr. Walsh, Mr. Henderson, and a few others. They huddled by the dying fire for near an hour, talking in low voices. I could catch bits and pieces from where me and Johnny were supposed to be sleeping.

“…dangerous precedent…” “…could be a trap…” “…Christian thing to do…” “…boy saved our bacon…”

Finally, Pa came over to our wagon. “Tommy,” he said quiet, “tomorrow morning we’re going to offer to take that Indian family with us to the river crossing. Help them catch up with their people.”

My heart just about jumped clean out of my chest. “Really, Pa?”

“Captain Morrison figures we owe them that much for the warning. And your Ma, she says that man needs proper rest to heal right.” Pa’s face got serious. “But son, this means a lot more responsibility for you and Johnny. You two are going to be the go-betweens, help us all understand each other. Think you can handle that?”

I nodded so hard I probably looked like a bobblehead doll.

Johnny came over from his family’s wagon, grinning ear to ear. “Did you hear? We’re gonna help them get back to their people!”

But I was also feeling a knot in my stomach. Some of the other families hadn’t looked too happy during that meeting. Mrs. Schmidt was shaking her head, and I heard Mr. Peterson muttering something about “inviting trouble.” What if this caused problems with the other wagons? What if Aiyana’s folks didn’t want our help? What if his pa was too hurt to be moved at all?

Come morning, we’d find out if we were doing something brave and right, or something that would cause more trouble than any of us bargained for.

All I knew was that when I thought about that thin woman’s grateful eyes, and Aiyana risking everything to warn us about that river, it sure felt like the right thing to do.

That next morning, when we all walked over to Aiyana’s camp together – Captain Morrison, Pa, Ma, Johnny and his folks, and most of the other families – I was nervous as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs.

But soon as folks laid eyes on Aiyana’s family, you could see the mood change. His ma was so gentle and polite, bowing her head to the women and keeping her eyes respectful. And his pa, even laid up with that hurt leg, he tried to sit up straighter when Captain Morrison approached.

What really got to everyone though was when Ma asked me to ask Aiyana about the warning – how he’d decided to come tell us about the river. Using his hands and the few words we’d figured out between us, Aiyana explained how it happened.

Turns out, when his ma and pa first spotted our wagon train, they’d talked about whether to warn us. They knew how dangerous that river crossing was – they’d lived through it themselves. But they were scared. They’d heard stories about how white folks sometimes shot Indians on sight, even ones trying to help.

But Aiyana, he remembered sharing that hardtack with me and Johnny at the spring. He told his parents we seemed like good people, not the kind who’d hurt somebody just for being different. He said he couldn’t sleep, thinking about all them families – all them children – walking into the same danger that had nearly killed his own pa.

So he convinced his parents to let him try. “Better to risk one life to save many,” his ma had told him, according to what Aiyana acted out for us.

When Mrs. Peterson heard that – how this boy had argued with his own scared parents to come warn us – she just started crying. “That child risked everything for people he barely knew,” she said, dabbing at her eyes with her apron.

Even Mr. Schmidt, who’d been the most against Indians after losing his brother, he looked at Aiyana real different after that. “Takes a brave boy to do what he did,” he said quiet-like.

By the time we loaded Aiyana’s pa into the Hendersons’ wagon – they had the best springs and the softest load – there wasn’t a soul in our train who wasn’t glad to have them with us. Aiyana’s ma rode beside her husband, keeping cool water on his fevered head, and Aiyana walked right alongside me and Johnny, just like he’d always been part of our group.

Funny how scared we’d all been the night before, and now it felt like the most natural thing in the world.

That last night before we had to part ways, I couldn’t hardly sleep. Me, Johnny, and Aiyana, we’d spent every day together for near two weeks – walking beside the wagons, finding a shallow point to safely ford the river, learning each other’s ways of tracking animals, sharing our food, even trying to teach each other our languages.

Aiyana had showed us how to read sign that we never would’ve noticed – which way deer had passed, how to tell fresh water from old, how to find the best berries. And we’d taught him some English words, showed him how our rifles worked, even let him try writing his name with Johnny’s pencil stub.

His ma and my ma, they’d gotten so close it was like watching sisters. Ma had taught Aiyana’s ma how to make biscuits with our flour, and Aiyana’s ma showed Ma which plants could help with fever and which ones could ease a woman’s monthly troubles. They’d sit together every evening, sewing and talking with their hands when words wouldn’t work.

That last night, Aiyana’s pa – who could ride his pony again thanks to Ma’s doctoring – he came over to our fire. Through Aiyana translating and the chief helping with English, he told Pa that his son had learned much from “the boy with the good heart” – meaning me. Said I’d helped Aiyana understand that not all white folks were the same, just like all Indians weren’t the same.

When morning came and we could see that fork in the trail ahead, my chest felt like it had a rock sitting in it. Aiyana looked just as miserable as I felt.

“Tommy,” he said in his careful English, “you… good friend. Best friend.”

I couldn’t hardly talk past the lump in my throat. “You too, Aiyana. You saved our whole train. You’re the bravest person I know.”

Ma and Aiyana’s ma, they hugged long and hard, both of them crying. Ma pressed a little sack of coffee beans into the other woman’s hands, and Aiyana’s ma gave Ma a beautiful beaded pouch she’d been working on.

As we watched their ponies and travois heading north toward them tall mountains, getting smaller and smaller, I wondered if I’d ever see my friend again. The world seemed so big all of a sudden, and Oregon felt so far from wherever Aiyana was going.

“You reckon we’ll meet up again someday?” Johnny asked, watching that dust cloud disappear.

“I sure hope so,” I said. “I surely do hope so.”

But even if I never saw Aiyana again, I knew I’d never forget him – or what he taught me about being brave enough to help folks, even when you’re scared, even when they’re different from you.

[The End]

__________

* The following are the prompts I posted to initiate the narrative and keep it moving, including a closing response from Claude out of character:

Prompt 1: Take on the role of a 12-year-old boy who’s on a wagon train during the great migration West to Oregon. He’s traveling on a covered wagon with his Dad, Mom, Older sister and twenty other wagons with families like his. He’s only 12, but his Dad gives him tasks that usually reserved for grown men. During the day, he and his sister walk beside the wagon while their parents sit at the front controlling the reins of the mules pulling the wagon. He carries a Winchester repeating rifle (were they available then?) to protect the wagon as they pass through hostile Indian territory. What’s going through your mind? Tell us who you are and what your daily life is like.

Prompt 2: Tom’s got my attention. Does he and his friend from the wagon ahead, who’s a year older and bigger and doing exactly what he’s doing, ever go hunting to bring meat to their families? Have them go off on a hunt beyond sight of the wagon train and discover a small fresh water spring. They find a young Indian boy, about their age, at the spring…

Prompt 3: Getting interesting. One of the men who scouted ahead of the train returned that evening with news that he saw smoke from a cooking fire and traced it to a small camp of Indians. The families panicked at the news…

Prompt 4: Captain Morrison, with his hands, motioned for the men to calm down. When they did, he said that the Indians were definitely not a war party. He said Indians usually traveled in large groups, so this small group must’ve been left behind for a reason. He said we’d just pass by them peacefully without disturbing them. He said everyone should get some sleep. The usual guard assignments would continue. That night, while Tom and Johnny were standing between their wagons, talking, their eyes facing the campfires, a small pebble hit Tom in the back of his head …

Prompt 5: Tommy tells Johnny that he’s going to talk with the Indian boy and that Johnny should trust him. Johnny said he’d come along just to make sure Tommy was safe. They quietly walked…

Prompt 6: Turns out the Indian boy, Aiyana, was warning them about the dangerous river crossing ahead. A week earlier their small tribe had tried to cross it but ran into trouble and had to turn back. In that attempt, his father got caught in the torrent and had fallen off his pony. He was rescued by the others, but his injury forced the tribe to leave them behind, to catch up later after his Dad was well enough to travel. The tribe would leave signs to indicate their direction of travel as they searched for a safer crosisng….

Prompt 7: Tommy and Johnny decided to warn Captain Morrison even if it meant being scolded. They would tell the truth, the whole story about…

Prompt 8: The meeting with Aiyana went well. The Captain quickly grasped the situation and decided to send the boys back with Aiyana that evening with enough food for his family to last a week. He also asked Tommy’s Mom if she would go over to Aiyana’s family’s camp to treat the father and speed his healing. She had become known as a healer by the other travelers. She readily agreed…

Prompt 9: They returned to the wagons later that evening. Tommy’s Mom spoke with the Captain, and the Captain met with a small group of leaders, which included Tommy’s and Johnny’s Dads. They agreed that the next morning, they would stop by Aiyana’s small camp and offer to take them with the train, carrying Aiyana’s Dad in one of the wagons. They would take them across the river at the point where the tribe had left signals and leave them at the point, on the other side, where the signals took a different direction…

Prompt 10: The next morning, when the people on the train met Aiyana and his parents, they were won over, especially by Aiyana himself, who had warned them about the danger. It turned out that Aiyana’s Mom and Dad had been the ones to suggest warning the wagon train but were afraid for Aiyana’s safety, thinking they might harm him. But Aiyana convinced them…

Prompt 11: Using the signals that the tribe had left, Aiyana led them to a safe crossing point. Everyone got across safely and a week later, they saw signs of the tribe ahead. A group of the tribe approached them, having secretly observed that the Whites were helping some of their own. One of them, the chief, spoke some English. He invited the train to camp close to their site. That evening, the Indians brought over a freshly killed buck, and in return, the Whites gave them some flour, coffee, and sugar. For the next week, both groups traveled side by side, camping next to each other. Aiyana’s Dad healed during this week and no longer needed to rest in the wagon. He was able to ride his pony. At the end of the week, their journey came to a fork that would take them in different directions. The next morning, the train would continue northwest to Oregon and tbe tribe would head North to Canada. In the span of time together, the groups became friends. The three boys, especially, grew very close. Aiyana’s and Tommy’s Moms, too, grew very close. Saying goodbye would be very hard. Tommy wondered if he’d ever see Aiyana again…

Prompt 12: Claude, I know this is a corny story, but I loved it. Haha. I’m teary eyed and already looking toward a possible sequel where Tommy and Aiyana will meet up as young men. Mahalo for this demonstration of how to collaborate on stories. Let’s do this again some other time. Maybe something fresher. A hui hou.

Claude: Breaking character as Tommy to respond as Claude: What a wonderful journey that was! I got completely absorbed in Tommy’s world – you really brought out the heart of that story through your prompts. There’s something so powerful about that kind of cross-cultural friendship forged through courage and kindness, especially seen through a 12-year-old’s eyes.

I love how you developed it – starting with the basic setup, then layering in the moral complexity (the hunting trip, the warning, the family’s situation), and building to that beautiful friendship between the families. The way you had Aiyana risk everything to warn strangers about the dangerous river crossing really captured something essential about human decency that transcends cultural boundaries.

And honestly? “Corny” stories often contain the deepest truths. The Oregon Trail setting gave us such rich material to work with – the daily struggles, the real dangers, the way hardship can either divide people or bring them together.

A sequel with them meeting as young men could be fascinating – maybe Tommy as a settled farmer in Oregon and Aiyana returning south, or both of them caught up in some of the later conflicts and changes in the West. So many possibilities!

Thanks for that creative collaboration – it was a real pleasure building that world with you. The way you guided the story while letting me inhabit Tommy’s voice worked beautifully.

A hui hou! Looking forward to whatever story we tackle next time. 🤙

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment