By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Gemini)

Editor

Introduction: In this follow-up to Oregon Trail: Where Two Cultures Collaborate, I worked with Gemini* to detail how the Fletchers (a fictional family) settled in Tualatin Valley, which is in the Willamette Valley, Oregon. -js

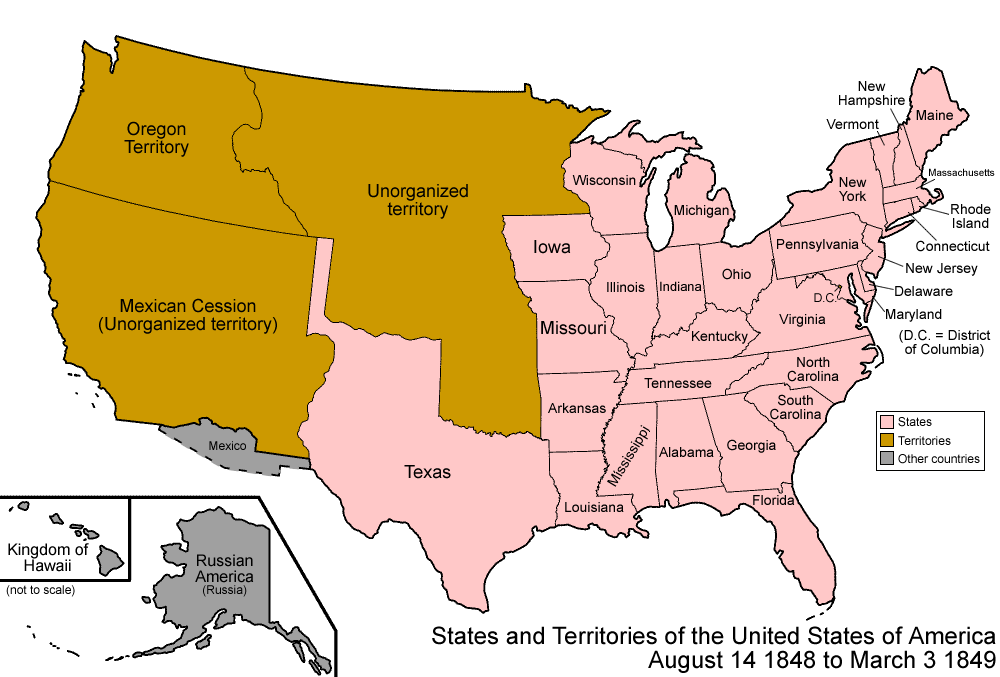

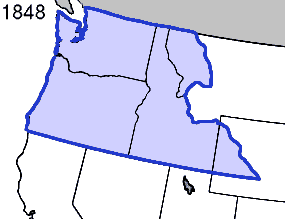

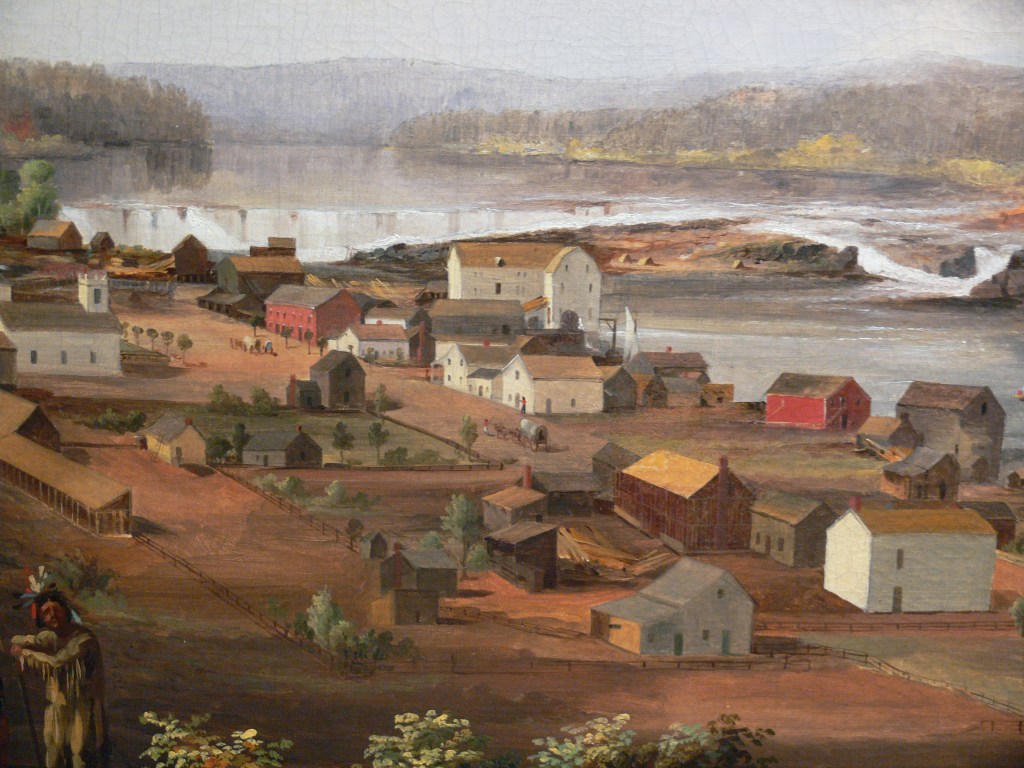

Traveling approximately 15 miles per day on average, the Fletchers’ 2,000-mile journey from Independence, Missouri, took approximately five months to complete. When they finally reached Oregon, their primary destination was the Willamette Valley.1 In 1850, the Oregon Territory comprised the entirety of the modern states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho as well as portions of present-day Montana and Wyoming that lie west of the Continental Divide. The official end of the trail was Oregon City, located at the northern end of the valley, and many people initially gathered there.2

From Oregon City, settlers dispersed throughout the Willamette Valley and other parts of the Oregon Territory.3 They were drawn by the fertile land and the promise of a new life.4 In 1850, the U.S. Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Act, which offered free land to white male or half-Indian settlers and their wives, further encouraging them to claim and settle on their own parcels of land.5 This act was a major factor in the settlement of the area.6

While Oregon City was the hub, settlers fanned out to establish farms and communities in various locations across the valley and beyond.7 In the Willamette Valley, an especially attractive area that may still have had available land was the Tualatin Valley. The advantages of this area included:

- Fertile land: The Tualatin Valley was known for its highly productive agricultural land, which was a major draw for settlers looking to establish farms. The land’s suitability for farming was in part due to the Atfalati people’s historical practice of controlled burning, which cleared and maintained large, open areas.

- Water sources: The valley was located in the drainage basin of the Tualatin River, a tributary of the Willamette River, and had numerous other streams and springs. Having a reliable water source was critical for farming.

- Access to Portland: While it was not an all-weather road at the time, a plank road (later known as Canyon Road) was built to connect the Tualatin Valley to the emerging port city of Portland. This provided farmers with a crucial link for transporting their agricultural goods to market.

To claim land in the Tualatin Valley, the Fletchers went through a rigorous and methodical process, shaped by the newly enacted Oregon Donation Land Act.

Claiming the Land

- Finding and Marking the Claim: The Fletchers’ first step was to locate a suitable piece of unclaimed land. In 1850, much of the most desirable land in the Willamette Valley had already been claimed under the provisional government, but the Tualatin Valley still had opportunities. The family found a parcel with good soil, a stream, and an accessible timber supply. After choosing the site, they “squatted” on the land and marked the corners of their claim.

- Registering the Claim: The family then traveled to the federal land office in Oregon City. The Donation Land Act of 1850 governed this process. The father, a U.S. citizen, claimed 320 acres, with an additional 320 acres for his wife, totaling a generous 640 acres. This was an unprecedented opportunity for a family to own such a large tract of land. The father would file the necessary paperwork, a formal declaration of his intention to reside on and cultivate the land.

- Residency and Cultivation: To secure legal title, the family was required to live on and make improvements to the land for four consecutive years. This meant they couldn’t just claim the land and leave it; they had to actively settle and farm it. The entire family would have been essential for this.

Settling the Land

The process of building a home and establishing a farm was a collective effort, with each family member playing a vital role.

- Building a Home: The family’s first priority was to construct a shelter before the rainy Oregon winter. With only basic tools and the help of their mules, they relied on the readily available timber to build a simple log cabin. Mr. Fletcher and Tommy fell trees, while Mrs. Fletcher and Sarah stripped bark and helped with chinking — filling the gaps between the logs with mud and moss. Building a home was a community affair, and the family received assistance from neighbors — including his friend Johnny Walsh, his family, and many other families from their wagon train — in a “cabin raising,” in exchange for their help on a future project. Their wagon served as a temporary home, with the mules’ canvas cover providing additional shelter.

- Clearing the Land: Once the cabin was built, the Fletchers’ next major task was clearing the land for farming. This was backbreaking work. The father and son fell trees and removed stumps. The mules were invaluable for this, pulling logs and clearing debris. Sarah and Tom were instrumental, helping to gather brush and rocks, and doing whatever they could to prepare the ground for planting.

- Starting the Farm: The family’s mules and wagon were their most important assets, as they could be used for plowing and transporting materials. A simple walking plow and other hand tools like hoes and a scythe were necessary to break ground and plant their first crops. They started with quick-growing, staple crops like corn and potatoes. In their first growing season, the Fletchers were able to clear and farm approximately 30 acres of their land. Considering the 640-acre size of their claim, this was only 5% of their land. The mother and Sarah were responsible for planting, tending a garden for vegetables, and preserving food for the winter. Tommy assisted his father with the heavy labor of farming, including planting, weeding, and eventually, harvesting.

- Daily Life and Community: Life was a constant cycle of work. The mother’s responsibilities included all domestic duties — cooking, cleaning, mending clothes, and providing healthcare for the family. The children, though young, were expected to contribute fully to the farm and household. The family’s success depended on their ability to work together and to forge relationships with their neighbors, as they relied on each other for assistance, community, and trade. Their isolation was profound, but the promise of land ownership was the driving force behind their labor.

Their Neighbors

It was very common for settlers like the Fletchers and Walshes to claim land in the same area as their friends, family, and neighbors from their wagon train. The long journey on the Oregon Trail forged strong bonds of mutual assistance and trust. These relationships, which were essential for survival on the trail, often extended into their new lives in Oregon.

Arriving in a new, unfamiliar territory, settlers had a natural inclination to stay near the people they knew and trusted. Settling near friends provided a crucial support system. They relied on each other for help with the monumental tasks of clearing land, building cabins, and planting crops. This cooperative effort, sometimes called a “cabin raising,” was a key part of early frontier life.

Furthermore, a group of friends or family members settling in the same vicinity formed the nucleus of a new community. They worked together to establish schools, churches, and other institutions, recreating a sense of the community they had left behind. The wagon train was not just a means of transportation; it was a temporary community that often became the foundation for permanent settlements in the West.

So, while the lure of free, fertile land was the primary motivation, the decision of where to claim that land was heavily influenced by social ties, with many settlers choosing to live near their trail companions.

Building a home and harvesting their first crop would have been a matter of survival for the family of four. With help from their neighbors, the process would have been challenging but achievable within a year.

Timeframe for Establishing the Farm

Building a simple log cabin with neighbors’ help, the Fletchers’ cabin took two weeks of intensive labor. The cabin provided basic shelter before the winter rains set in.

After the cabin was finished, the family’s clearing and preparation of the land for planting was an ongoing effort. Since the family arrived in the spring of 1850, they planted their first crops of corn and potatoes that season.

- Corn and Potatoes: These staple crops were chosen because they grew relatively quickly and provided a high caloric yield. Potatoes, planted in early spring, could be harvested in 3-4 months. Corn, planted around the same time, would mature in 4-5 months. The first harvest would likely have been in late summer or early fall of 1850.

- Other Foods: In addition to corn and potatoes, the family relied on a small garden for other vegetables like beans, squash, and pumpkins. They also hunted wild game, fished, and foraged for berries and other wild edibles to supplement their diet.

Selling the First Crop and Earnings

Selling their first crop was challenging due to limited infrastructure. The family had to transport their surplus produce by wagon to the nearest settlement with a market, likely Oregon City or the emerging town of Portland. They sold their goods to merchants, other settlers, or to the growing number of new arrivals.

The earnings from their first harvest depended on the size of their crop and market prices, which fluctuated wildly. To understand the value of their earnings, consider the following:

- Buying Power: In the early 1850s, a laborer’s daily wage was roughly $1 to $1.50. The price of a bushel of potatoes might have been around $0.50 to $1.00, and a bushel of corn could have sold for a similar price.

- Economic Context: A family’s primary goal in the first year was self-sufficiency. Any earnings from their crops would not have been a source of significant wealth but would have been used to purchase essential goods they could not produce themselves, such as:

- Tools and implements: A better plow or scythe.

- Livestock: Chickens or a pig.

- Supplies: Coffee, sugar, salt, and flour, which were considered luxuries.

- Clothing and household items.

Education in the Tualatin Valley

By 1850, the Tualatin Valley had a small but growing population, and the importance of education was recognized by the settlers. While a formal public school system was still in its infancy, several community-based schools had been established.

- Early Schools: The first schools in the area were often run out of private homes or a simple log cabin built by the community. They were funded by parents who paid a small fee, and the teacher’s salary was often paid in goods or services rather than cash.

- Curriculum: Instruction was basic, focusing on reading, writing, and arithmetic. The school year was short, and attendance depended on the family’s need for their children’s labor on the farm.

- Example: The first school in the Tualatin Valley was established as early as 1845. By 1850, other communities were following suit, meaning the Fletchers’ children had access to some form of education.

In Oregon’s Willamette Valley, preparing for winter was a critical and relentless effort, primarily handled by the women and children. The winter season, characterized by cold temperatures and persistent rain, typically lasted from November to March or April.

Food Preparation and Storage

The preservation of food was essential for surviving the long, lean winter months. Mrs. Fletcher and Sarah, like other women, employed several methods:

- Drying: Fruits (apples, pears, prunes) and some vegetables (corn, beans) were sliced and dried in the sun or by a fire. Strips of wild game or butchered meat was also dried into jerky.

- Salting and Smoking: Meat was heavily salted to draw out moisture and then smoked to preserve it. Fish from local rivers was also salted.

- Pickling: Vegetables, such as cucumbers and cabbage (for sauerkraut), were pickled in brine or vinegar.

- Root Cellars: A family dug a pit or a small, enclosed space into the side of a hill to create a root cellar. Lined with straw or wood, this cool, dark, and humid environment was perfect for storing root vegetables like potatoes, carrots, and turnips throughout the winter.

- Rendering Fat: Lard from butchered pigs was rendered and stored in crocks. It was used for cooking, baking, and making soap.

- Canning: While early forms of canning existed, the technology for hermetically sealed jars was not widespread until later in the 19th century. Early settlers might have used glass jars with wax seals, but this was a less reliable method.

Daily Life in Winter

Winter days were a dramatic change from the demanding outdoor labor of spring, summer, and fall.

- Indoor Chores: With outdoor work severely limited, the family’s focus shifted to indoor tasks. Mrs. Fletcher and Sarah spent their days mending and making clothes, weaving, spinning wool, churning butter, and preparing meals. The fireplace was the center of the home, providing heat for warmth and cooking.

- Education and Reading: This was a time for reading by firelight. The family’s few books, often the Bible and a small collection of readers, would have been reread many times.

- Repairs: Mr. Fletcher and Tommy spent time repairing tools, making new handles for implements, and preparing for the next farming season. They also chopped and hauled firewood to keep the home warm.

- Community: Winter was a time for more social interaction. Neighbors visited, a rare luxury during the busy seasons.

Bartering and Food

Bartering was the primary form of economic exchange in the early settlements. Foodstuffs were the most common items of trade. If one family had a surplus of corn, they might trade it for another family’s potatoes, salt, or smoked meat. This community reliance was essential, as no single family could produce everything they needed.

Typical Meals

A family’s diet was based on what they could grow, raise, or hunt.

- Breakfast: Often a hearty meal to start the day. Cornmeal mush or “hoecake” (a type of flatbread), with milk, might be served. If they had a pig, they might have salt pork. Coffee was a luxury and often a highly valued trade item.

- Lunch: A midday meal would be simple. Leftovers from the night before, perhaps some bread, cheese, or pickled vegetables.

- Dinner: The main meal of the day, usually served in the late afternoon. It would feature a stew or a pot of boiled meat and potatoes, often with whatever vegetables were available. Baked goods, like biscuits or a pie made from dried fruit, would be a welcome treat.

Water Sources

- Likelihood of a Stream: Given the Tualatin Valley’s geography, it’s highly likely that a settler family would have tried to claim land with a stream or spring on it. The Fletchers had a stream that was a natural water source. It provided water for drinking, cooking, bathing, and, crucially, for livestock.

- Digging a Well: If a natural water source wasn’t available, digging a well was a necessity. This was a difficult and time-consuming task, often done by hand. It would have been a priority, as a reliable water source was non-negotiable for survival.

Outhouses and Sanitation

An outhouse, or privy, was a standard feature of any settler’s homestead. It was a simple structure — a small, wooden shack built over a deep pit. The father and son would have built it from spare timber, and it would have had a simple bench with one or two holes for use. It was located a safe distance from the cabin and the well to prevent contamination.

Indoor Lighting

Indoor lighting was minimal and precious.

- Firelight: The fireplace was the main source of light and warmth.

- Candles: Candles were a luxury. They could be made from animal fat (tallow) or beeswax, but this was a time-consuming process. The family would have rationed their use, reserving them for essential tasks.

- Oil Lamps: Simple lamps, burning animal fat or oil, would have also been used.

Building a Barn

- Necessity: Building a barn was a high priority, though not as immediate as building the family’s home. A barn was essential for sheltering livestock (mules, any chickens or pigs they acquired), and for storing hay, grain, and tools.

- Timeline: Building a barn would likely have happened within the first year or two. The Fletchers’ basic log barn had been built in three weeks with the help of neighbors, similar to the cabin-raising. It was a more primitive structure than later barns, but sufficient for their immediate needs. The family then continuously improved their barn and other structures as they settled into life on their claim.

Hunting and Fishing on Their Own Land

Hunting and fishing were not just a hobby for settlers; they were a vital and reliable source of protein, especially during the early years before livestock could be raised.

- On-Property Resources: The running stream and forested area on the Fletchers’ property provided an excellent opportunity for hunting and fishing. The Willamette Valley was rich with game and fish, and settlers prioritized land with these resources.

- Open Hunting Areas: While they could hunt on their own land, they also joined neighbors to hunt in larger, nearby forested areas, or in the Coast Range mountains. Fishing in the larger rivers, such as the Tualatin or the Willamette, was a communal activity as well.

Typical Game and Fish

The Willamette Valley was abundant with a variety of game.

- Game:

- Deer: Both black-tailed and mule deer were common and a primary source of meat.

- Elk: Herds of Roosevelt elk could be found in the more heavily forested areas.

- Small Game: Rabbits, squirrels, and various wildfowl such as ducks, geese, and wild turkeys were also hunted.

- Bears and Cougars: While less common, these animals were a potential threat and also a source of meat and hides.

- Fish:

- Salmon and Steelhead: The rivers of the Willamette Valley were teeming with salmon and steelhead runs, which were a cornerstone of the Native American diet and a crucial resource for settlers.

- Trout: Various species of trout were plentiful in the smaller streams and rivers.

- Other Fish: Fish such as bass and sturgeon were also be found in the larger rivers.

Rifle of Choice

The settlers who traveled the Oregon Trail were, by and large, self-sufficient individuals who brought with them the tools and weapons they knew best. Their rifle was a trusted and essential tool for both hunting and defense.

Typical Rifle: The most common rifle was a percussion-lock rifle, often of the “plains rifle” or “long rifle” style. These were single-shot firearms, valued for their accuracy and power. Tommy’s percussion cap system, which had largely replaced the older flintlock system by 1850, was more reliable in wet weather, a key advantage in Oregon’s climate.

Make and Model: While there wasn’t a single “make and model” like we have today, these rifles were often made by various gunsmiths. One of the most famous and widely respected makers of these rifles was the Hawken brothers (Jacob and Samuel Hawken) of St. Louis. Their “Hawken rifle,” a heavy, powerful, and accurate percussion rifle, was a favorite among mountain men and was carried by many settlers on the Oregon Trail. While a true Hawken rifle was expensive, many settlers owned similar rifles made by other gunsmiths, often called “Hawken-style” rifles. These were known for their rugged construction and reliability, making them the ideal choice for a frontier family.

A Deer Kill

In this early Oregon settlement, a deer was a significant and celebrated event, providing a wealth of food and resources. The entire family was involved in the process, from getting the deer home to preparing it for a year’s worth of meals.

Once Mr. Fletcher and Tommy shot a deer on their property, they had to get it back to the cabin. For a buck, which could weigh over 200 pounds, this was a difficult task. The two mules were invaluable here. The family used a sledge or a simple travois made from poles to drag the deer back to the cabin. The father and son worked together to hoist it onto a mule for a shorter distance.

Divvying and Preservation

Once back at the cabin, the deer would have been quickly processed to prevent spoilage. This would be a family affair, with each person having a job.

- Butchering: The father and son would be responsible for butchering the deer, a skilled task they learned out of necessity. They would have used their knives to skin and quarter the carcass.

- Immediate Meals: The best cuts of meat, such as the loin and hindquarters, would be set aside for immediate meals. The mother and daughter would cook venison steaks or roasts over the fire. Nothing would go to waste; the organ meats (liver, heart, kidneys) would be eaten first, as they were the most perishable.

- Preserving and Storing: The remaining meat would be preserved.

- Salting and Curing: The meat would be heavily salted to draw out moisture and act as a preservative.

- Drying: Strips of venison would be hung on racks near the fire or in the smokehouse (if they had one yet) to dry and become jerky. This was a crucial method for long-term storage, as jerky could last for months.

- Rendering: The fat (tallow) from the deer would be rendered down for cooking and other uses.

Prepping the Skin

The deer skin, or hide, was far too valuable to waste.

- Tanning: The most common method of tanning the hide would have been brain-tanning, a process passed down from Native American traditions. The hide would be scraped clean of all flesh and hair, then soaked in a mixture of water and the deer’s own brains (which contain an emulsifying oil). This made the hide soft and pliable.

- Future Use: The tanned hide could be used for a variety of purposes:

- Clothing: For making durable pants, jackets, or moccasins.

- Bedding: As a warm and soft sleeping mat.

- Leather: For making straps, bags, or other items.

Hunting and Fishing in Winter

Hunting and fishing were absolutely necessary in winter.

- Winter Hunting: While the fall was the prime hunting season, settlers would still hunt in winter. Deer and elk were harder to find, but smaller game like rabbits, squirrels, and wildfowl would have been pursued.

- Ice Fishing: If a pond or a slow-moving part of the river froze over, the family could have engaged in ice fishing.

- Trapping: Trapping small game was a common way to supplement the larder.

Danger of Being Attacked by Bears

They were in very real danger of being attacked by bears, though it was not a daily threat.

- Black Bears and Grizzlies: Both black bears and grizzly bears inhabited the region. Black bears were more common, and while typically not aggressive toward humans, they could be a threat, especially if they were cornered, surprised, or protecting cubs. Grizzlies, however, were much larger and more dangerous.

- Threats: The bears were a danger not only to the family but also to their livestock. A bear could kill a pig, a mule, or raid their food stores.

- Defense: The family’s rifle was their primary defense against a bear attack, but their best protection was simply to be vigilant and make a lot of noise while walking through the woods to avoid surprising a bear.

Tommy’s rifle was certainly capable of taking down a bear, but it was a dangerous and difficult undertaking. The Hawken-style percussion rifles were powerful, often firing a heavy lead ball of .50 caliber or greater. Such a rifle, in the hands of a skilled marksman, could be lethal to a bear, but it was not a guaranteed one-shot kill. A wounded and enraged bear, particularly a grizzly, was a formidable and deadly opponent. The rifle was their best defense, but also a weapon that required an understanding of its limitations and the immense power of the animal.

Settlers did not actively hunt bears for meat in the same way they hunted deer or elk. While bear meat was edible and was certainly consumed, especially in self-defense kills, it was not the preferred game. Bear meat was often considered greasy and less palatable than venison or other game. A bear hide, however, was a valuable resource for a rug, bedding, or trade.

Most bear kills were a result of either a perceived threat or a direct attack. A bear could be killed for:

- Self-Defense: If the family was directly threatened.

- Protecting Livestock: Bears, especially grizzlies, were a major threat to a family’s mules, chickens, or pigs.

- Raiding Food Stores: A bear raiding a root cellar or a smokehouse could destroy a winter’s worth of food, and would be killed as a necessity.

- Opportunistic Hunting: If a bear was spotted and presented a safe shot, the settler might have taken it, but it was considered a much riskier hunt than a deer.

Dating and Meet-Ups

Young men and women on the Oregon frontier did date and have meet-ups, but it was much different from modern dating. The social life of young people was closely tied to community gatherings.

Dating was less about one-on-one outings and more about group activities and community events. Young people typically met and courted at social gatherings.1

- Church gatherings were a primary meeting place, as religion was a central part of settler life.

- Dances were popular, often held in a neighbor’s large cabin or a community hall. These were lively events with music from fiddles and other instruments.

- “Singing schools” and other educational or social groups provided more structured ways for young people to interact.

- Work bees, where neighbors came together for tasks like barn-raisings or harvests, also offered opportunities for young men and women to get to know each other.

There was a strong emphasis on chaperoned activities, as young men and women were rarely left alone together. Their social interactions were carefully monitored by the community and their families.

Age for Dating and Marriage

While there wasn’t a strict “dating age,” young people typically started attending these social gatherings and showing interest in courtship around 15 or 16 years old.

Marriage happened at a young age compared to today.2 The average age for women to marry was around 18 to 20, while men were often a couple of years older, marrying in their early 20s.

Requirements for Tommy to Marry

For young men like Tommy and Johnny to marry, the primary requirement was financial stability and the ability to support a family. This was a practical necessity on the frontier.

- Securing Land: A young man was expected to have already claimed his own land, likely through the Donation Land Act, and begun the process of making it a working farm.

- Building a Home: He needed to have built or be in the process of building a log cabin for his future family.

- Proving Self-Sufficiency: He had to demonstrate that he could provide for a wife and future children, which included having the tools, livestock, and skills necessary to be a successful farmer.

In this society, a marriage was not just a romantic union but a new economic partnership. A young man’s ability to secure land and build a home was the clearest signal that he was ready to take on the responsibilities of a husband and father.

How Tommy Would Claim Land

By his late teens or early 20s, when Tommy decides to claim his own land to marry, he would follow a similar process to his father but with a slightly different set of rules, as he would be arriving after the initial deadline.

- Reaching the Age of Majority: He would have to wait until he was at least 18 years old.

- Finding Available Land: He would need to find a suitable, unclaimed parcel of land. As the best land in the Tualatin Valley was claimed in the early 1850s, he might have to look further afield, perhaps into the foothills or other less-traveled parts of the valley.

- Claiming the Land: He would have to physically “squat” on the land, marking his claim and making it his residence.

- Registering the Claim: He would then travel to the federal land office in Oregon City (the main land office for the territory) and file a formal claim. Because he would have arrived after the 1850 deadline, the amount of land he could claim would be less generous:

- If he was unmarried: He would be eligible for 160 acres.

- If he was married: He and his wife would be eligible for a combined 320 acres.

- Meeting the Requirements: He would be required to live on the land and make improvements for four years to receive the final title.

The family’s best strategy for Tommy would be to find a claim adjacent to or very near their original farm. This would keep the family close, allowing the father and son to work together, share tools and knowledge, and support each other’s claims. This was a common practice, as families often worked to secure land for their children and extend their holdings as a family unit.

Tommy’s parents would have several options for acquiring land for their son, with their choices depending on the timing and circumstances.

Pre-Claiming Land

The most straightforward way for Tommy’s parents to help him would be to secure the land for him in advance. Under the Donation Land Act of 1850, a family could stake a claim larger than their immediate needs, with the intention of giving a portion to their children when they came of age. While the act was designed to grant land to individuals, a family could lay claim to a large parcel, and later, the son could take over a section of it.

For example, if Tommy’s parents claimed 640 acres as a married couple, they could ensure that a section of that land, perhaps 160 acres, was situated next to a good water source or timber. They could work to clear and improve this portion, making it a more attractive and ready-to-farm plot for Tommy. Tommy could then live on and improve this land, and when he came of age and was ready to marry, he could formally register his own claim to it.

Assisting with the Son’s Claim

If Tommy’s parents could not pre-claim the land for their son, they would provide critical assistance for him to stake his own claim when he came of age.

- Financial Support: Tommy’s parents would provide him with the tools, livestock, and supplies he needed to get started, such as a plow, seeds, and a mule. This was a crucial first step, as Tommy would have little capital on his own.

- Labor: The family would work together to help Tommy clear his land and build his cabin. This collaborative effort was a cornerstone of frontier life, and without it, a young man would have found it nearly impossible to establish his own homestead.

- Guidance: Tommy’s parents would also provide him with guidance and knowledge, teaching him how to farm the land, hunt, and navigate the bureaucratic process of the land office.

The Fletcher family’s goal would be to find an unclaimed parcel of land adjacent to their own. This would create a consolidated family farm, allowing for shared resources, mutual protection, and a stronger social and economic unit. If adjacent land wasn’t available, they would seek a nearby unclaimed parcel. The availability of desirable land diminished over time, so Tommy would have to take whatever was available.

[The End]

__________

* Prompts used in my collaboration with Gemini:

Prompt 1: Hi, Gemini.In 1850, where did settlers from the Oregon Trail settle when they reached Oregon?

Prompt 2: Where in Oregon would these 1850 settlers most likely settle after their long trek? Select a specific farming area that might’ve been especially attractive to them and was still available? What were the advantages of this area?

Prompt 3: The Tualatin Valley seems like a wonderful choice. How would a family of four — Dad, Mom, 13-year-old daughter and 12-year-old son — claim their land and begin settling it? They had two mules that pulled their wagon to Oregon and their wagon and some basic tools.

Prompt 4: Did these settlers often claim land in the same area as their friends from the wagon train they arrived in?

Prompt 5: How long would our family of four, with help from their wagon train neighbors, have taken to build a home and harvest their first crop? The crop would consist of corn and potatoes? Other foods? How would they sell the crop? How much would they have earned, translated into buying power at the time and place? Were there schools in the Tualatin Valley?

Prompt 6: How did they (the women?) prepare food for storage for Oregon’s winter months! How did they spend their days in the winter? How long was winter? Did they barter foodstuff with neighbors? What would a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner be like? Would it be likely that a stream passed through their property? A river alongside their property? If not, would they be able to dig a well? Did they build outhouses? How? What did they do for indoor lighting? Was building a barn a necessity? How long would that have taken?

Prompt 7: Was hunting and fishing a reliable source of meat? Would they be able to do it on their own land if they had a stream running through it and ample forests? Or would they have to travel to open hunting/fishing areas close by? What kind of game and fish did they bring home? What was there typical rifle of choice? Make and model?

Prompt 8: How would the father and son of our family of four have gotten a deer shot on their land, home? How would they divvy it up for preservation and immediate meals? How did they dry, preserve, and store the meat? How did they prep the skin for future use? Did they hunt and fish during the winter? Were they in danger of being attacked by bears?

Prompt 9: Was their rifle capable of taking down a bear? Did they actively hunt bear for meat or did they kill and eat them in self-defense?

Prompt 10: Did young men and women date or have meet-ups? At what age did they start dating? Get married? What did a young man require to get married…

Prompt 11: How would the young man in our family of four go about using the Donation Land Act to claim land, preferably in the same area or close by?

Prompt 12: How would the parents in our family of four go about acquiring land adjacent to or close to theirs for their son!

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment