By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

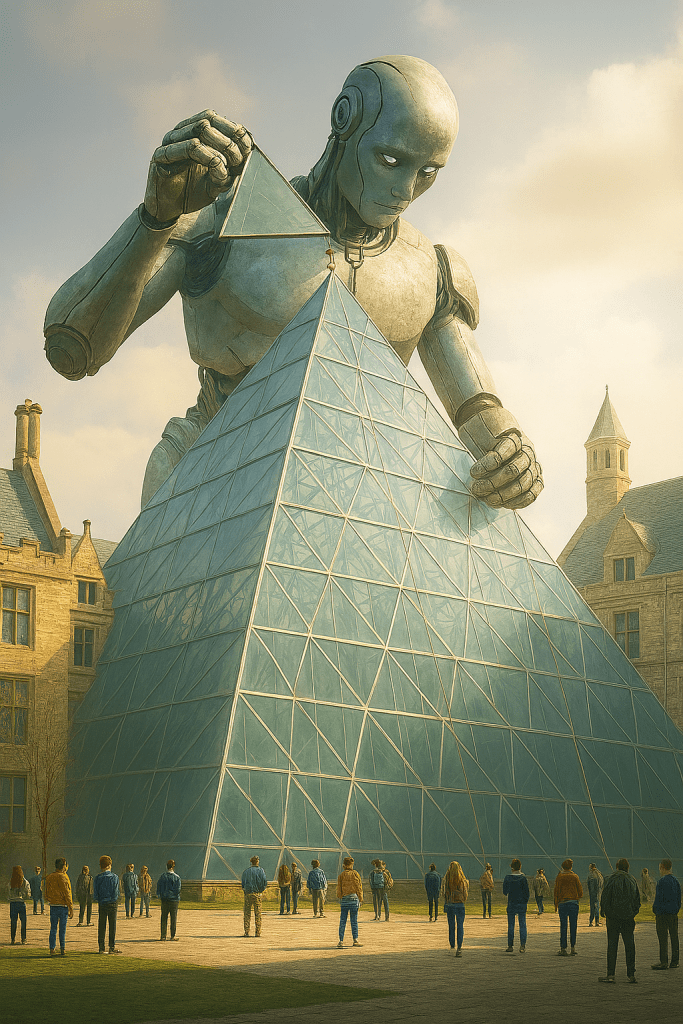

Claude: The integration of artificial intelligence into education represents far more than a technological upgrade to existing systems. It constitutes a fundamental challenge to the paradigms that have structured formal learning for over a century. The current educational model, rooted in industrial-era assumptions about knowledge transmission, standardization, and credentialing, is encountering anomalies that its framework cannot adequately address. These disruptions signal not merely the need for incremental reform but rather a paradigmatic shift in how we conceive of learning, teaching, and intellectual development itself.

The Current Paradigm and Its Foundations

To understand how AI disrupts education, we must first articulate the paradigm it challenges. The dominant educational model in most developed nations emerged from nineteenth and early twentieth-century industrialization. This system rests on several interconnected assumptions: that knowledge exists as a relatively stable body of information to be transmitted from expert teachers to novice students; that learning progresses through standardized, age-based sequences; that educational quality can be measured through uniform assessments; that schools and universities serve as gatekeepers to knowledge and credentials; and that the teacher’s primary role involves delivering content and evaluating student mastery.

This paradigm has proven remarkably resilient, surviving numerous reform movements and technological introductions. Textbooks, calculators, computers, and the internet were all absorbed into existing structures without fundamentally altering the basic relationship between teacher, student, and knowledge. The classroom lecture, the homework assignment, the examination, and the degree credential have remained largely intact as the organizing features of educational experience.

The Anomalies AI Introduces

AI systems, particularly large language models and adaptive learning platforms, introduce several profound anomalies that strain this traditional framework to its breaking point.

The Democratization and Personalization of Expertise

Perhaps the most significant anomaly concerns access to expertise itself. Traditional education operates on a scarcity model where expert knowledge is valuable precisely because it is difficult to access outside formal institutional channels. A student needs a teacher, a professor, or at minimum a well-curated textbook to access sophisticated explanations of complex topics. AI fundamentally disrupts this scarcity. A student with internet access can now engage with an AI system capable of providing expert-level explanations, tailored to their specific level of understanding, available instantly and at virtually no marginal cost.

This creates an anomaly because the traditional justification for educational institutions—that they provide access to expertise—becomes less compelling. When a high school student in rural Montana can receive a detailed, personalized explanation of quantum mechanics or post-colonial literary theory at three in the morning, the institutional monopoly on knowledge transmission begins to erode. The paradigm assumed that access to expertise required physical proximity to experts or at least expensive published materials. AI makes expertise ambient and ubiquitous.

The Collapse of Assessment Validity

A second critical anomaly emerges in assessment. The current paradigm relies heavily on written assignments, problem sets, and examinations to evaluate student learning. These assessments rest on the assumption that the work product reflects the student’s own understanding and capabilities. AI systems capable of generating essays, solving mathematical problems, writing code, and even conducting research fundamentally undermine this assumption.

Educational institutions initially responded to this challenge by attempting to detect AI-generated work or by prohibiting AI use entirely. However, this approach reveals the paradigm’s inadequacy. Detection methods remain imperfect and create an adversarial relationship between students and institutions. More fundamentally, prohibiting tools that students will inevitably use in their professional lives seems pedagogically incoherent. If a lawyer, engineer, or analyst will routinely use AI assistance in their work, what exactly are we measuring when we insist students complete assignments without such tools?

The anomaly runs deeper than mere cheating concerns. Traditional assessments assume that demonstrating individual mastery of content represents the primary learning goal. But if AI can perform these tasks competently, what should education actually develop? The current paradigm lacks a framework for answering this question because it assumes that knowledge acquisition and demonstration are themselves the endpoints of education.

The Transformation of Information Literacy

A third anomaly concerns the nature of information literacy itself. The current paradigm teaches students to locate, evaluate, and synthesize information from various sources. Library research skills, critical reading, and source evaluation have been understood as fundamental scholarly competencies. AI systems that can instantly aggregate information from thousands of sources, provide syntheses, and even evaluate source credibility based on vast training data create a profound challenge to this framework.

Traditional information literacy assumes a world where finding relevant information represents a significant challenge and where human judgment is necessary to separate reliable from unreliable sources. AI makes information retrieval trivial and provides sophisticated analytical capabilities that surpass what most students can achieve through manual research. This doesn’t eliminate the need for critical thinking, but it fundamentally changes what critical thinking means and how it should be taught.

The Questioning of Disciplinary Boundaries

AI systems also create anomalies around disciplinary organization. Traditional education divides knowledge into distinct subjects—mathematics, literature, biology, history—each taught separately with specialized teachers or professors. This organization reflects both practical constraints and epistemological assumptions about how knowledge is structured. AI systems, by contrast, operate across disciplinary boundaries fluidly. A conversation with an AI might move seamlessly from discussing the mathematical principles underlying climate models to the historical development of environmental policy to literary representations of ecological crisis.

This creates an anomaly because students increasingly encounter a mode of engaging with knowledge that doesn’t respect the carefully maintained boundaries that structure their formal education. The paradigm assumes that disciplinary specialization represents the natural and necessary organization of knowledge, but AI suggests that this organization might be more contingent and less epistemologically fundamental than previously assumed.

Why a New Paradigm Becomes Necessary

These anomalies, taken together, suggest that incremental adjustments within the existing framework prove insufficient. When the fundamental assumptions of a paradigm—that institutions monopolize access to expertise, that individual demonstration of knowledge mastery can be reliably assessed, that information literacy means manual research skills, and that disciplinary boundaries reflect natural divisions—all face simultaneous challenge, the paradigm itself becomes questionable.

The new paradigm must reconceptualize education’s fundamental purposes. Rather than focusing primarily on knowledge transmission and assessment, education needs to develop capacities that remain distinctly human even in an AI-rich environment. This includes creative and critical thinking that goes beyond information synthesis, ethical reasoning about how to use powerful tools responsibly, collaborative skills that leverage both human and artificial intelligence effectively, and metacognitive awareness about one’s own learning processes and how they differ from machine processing.

Additionally, the new paradigm must reconceive the teacher’s role. Rather than primarily serving as content deliverers and assessors, teachers become designers of learning experiences, coaches who help students develop sophisticated thinking, and guides who help young people navigate an information-rich environment. The teacher’s expertise shifts from knowing the most information to understanding how learning works and how to create conditions that foster genuine intellectual development.

Implications for School Curricula

The shift toward this new paradigm requires substantial changes in what schools teach and how they organize learning. At the primary and secondary levels, several curricular transformations become necessary.

Integration of AI Literacy from Early Education

Schools must introduce AI literacy not as a separate subject but as a fundamental dimension of learning across all domains. This doesn’t mean teaching children to code AI systems, but rather helping them understand how these tools work, what their capabilities and limitations are, and how to use them effectively and ethically. A middle school science curriculum might include units where students use AI to explore scientific concepts, but also explicitly discuss what the AI does well, where it makes mistakes, and how it differs from human scientific reasoning.

Elementary schools might incorporate AI tools into writing instruction, but focus on teaching children to use AI as a brainstorming partner or editor while developing their own voice and ideas. Mathematics education could leverage AI for personalized practice while ensuring students understand underlying concepts rather than merely getting correct answers. The goal is to raise a generation that views AI as a tool to be used thoughtfully rather than either a magical oracle or a threatening replacement for human capability.

Emphasis on Creative and Critical Synthesis

With AI handling routine information retrieval and basic synthesis, curricula must shift toward developing higher-order thinking. This means more emphasis on open-ended problems, creative projects, and critical analysis that requires genuine judgment. A history curriculum might move away from memorizing dates and facts—which AI can provide instantly—toward analyzing historical interpretations, evaluating conflicting narratives, and constructing arguments about historical causation.

English language arts might emphasize helping students develop distinctive voices, make sophisticated rhetorical choices, and engage deeply with literature’s aesthetic and emotional dimensions—areas where AI capabilities remain limited. Science education could focus more on experimental design, hypothesis generation, and the interpretation of ambiguous results rather than procedural problem-solving.

Project-Based and Collaborative Learning

The new paradigm suggests increased emphasis on sustained projects where students work collaboratively to address complex, multifaceted problems. These projects should explicitly incorporate AI tools while requiring human judgment, creativity, and ethical reasoning. A high school might organize interdisciplinary projects where students address local community challenges—designing sustainable urban green spaces, analyzing public health data to propose interventions, or creating multimedia narratives about local history—using AI as one tool among many.

Such projects resist easy automation because they require contextual understanding, stakeholder engagement, iterative refinement based on feedback, and integration of multiple perspectives. They also better reflect how AI will actually be used in professional contexts, where it augments rather than replaces human decision-making.

Metacognitive and Reflective Practice

Schools need to incorporate explicit instruction in metacognition—thinking about thinking. Students should regularly reflect on their learning processes, consider how they approach problems differently from AI systems, and develop awareness of their own cognitive strengths and weaknesses. This might involve keeping learning journals, participating in structured reflection sessions, or engaging in peer discussions about problem-solving strategies.

Such practices help students understand themselves as learners and develop the self-direction necessary for lifelong learning. They also create a foundation for thoughtful AI use, as students who understand their own thinking can better judge when AI assistance is helpful versus when it might shortcut necessary cognitive work.

Implications for College and University Education

Higher education faces even more profound challenges from AI, as the traditional university model rests heavily on the assumptions being disrupted. The implications for colleges and universities touch every aspect of their operation.

Rethinking Undergraduate Core Curricula

Many universities organize undergraduate education around a liberal arts core that aims to provide broad knowledge across disciplines. This model assumes that encountering diverse bodies of knowledge develops intellectual flexibility and cultural literacy. With AI providing instant access to information across domains, universities must articulate what these core curricula develop beyond knowledge acquisition.

The new paradigm suggests core curricula should focus on developing intellectual capacities and habits of mind rather than covering content. This might mean organizing courses around fundamental questions that require integrating multiple perspectives, sustained inquiry projects that develop research capabilities, and seminars emphasizing dialogue and argument rather than lecture-based information delivery. A university might redesign its core around themes like “Systems and Complexity,” “Evidence and Interpretation,” “Creativity and Innovation,” and “Ethics and Values,” with each theme explored through multiple disciplinary lenses but focused on developing capabilities rather than transmitting facts.

Transformation of Major Programs

Academic majors traditionally provide deep specialization in a disciplinary area, with students progressing through increasingly advanced content. AI disrupts this model particularly in fields where professional practice involves information processing, analysis, and routine judgment. Computer science programs can no longer focus primarily on coding skills when AI can generate code. Business programs must rethink curricula that emphasize case analysis when AI can perform sophisticated business analysis. Legal education faces questions about the value of training students in research and document drafting that AI increasingly handles.

The response cannot be simply to prohibit AI use in these programs. Instead, majors must focus on developing judgment, creativity, and expertise that complements AI capabilities. A computer science program might emphasize software architecture, user experience design, and ethical considerations in technology development rather than routine programming. Business education could focus on strategic thinking, organizational leadership, and navigating ambiguity—domains where human judgment remains essential. Law schools might emphasize negotiation, courtroom advocacy, client counseling, and legal reasoning rather than memorization and document production.

Graduate and Professional Education

Professional programs face particular pressure because they explicitly prepare students for careers where AI is rapidly changing practice. Medical schools must consider how to train physicians when AI can interpret diagnostic images, suggest treatments based on vast medical literature, and even conduct preliminary patient interviews. Engineering programs must prepare students for a world where AI assists with design optimization, simulation, and routine calculations.

The new paradigm suggests professional education should emphasize integration of AI tools into expert practice, development of judgment in ambiguous situations, communication and collaboration skills, and ethical reasoning about technology use. Medical education might involve extensive simulation training where students practice using AI diagnostic tools while developing their own clinical reasoning. Engineering programs could focus on systems thinking, failure analysis, and innovative design while teaching students to leverage AI for routine aspects of their work.

Pedagogical Transformations

Beyond curricular changes, the new paradigm requires fundamental shifts in how teaching occurs.

From Lecturing to Facilitating

The traditional lecture, where a professor delivers content to assembled students, becomes increasingly difficult to justify when students can access similar or better explanations from AI at any time. This doesn’t mean lectures disappear entirely—inspiring presentations, demonstrations of expert thinking, and communal exploration of ideas retain value—but they can no longer constitute the primary mode of instruction.

Instead, class time should focus on activities that require human interaction: collaborative problem-solving, discussions that build on diverse perspectives, hands-on experimentation, and working through confusion together. A physics professor might assign students to learn certain concepts using AI tutoring before class, then use class time for laboratory work, group problem-solving, and discussion of conceptual difficulties. A literature professor might have students read texts and generate initial interpretations using AI, then use class sessions to compare these interpretations, identify their limitations, and explore readings the AI missed.

Assessment Redesign

Perhaps the most challenging pedagogical implication involves assessment. Traditional examinations and papers, completed individually without AI, increasingly fail to measure meaningful learning. The new paradigm requires authentic assessment that reflects how students will actually use knowledge and tools.

This might involve portfolio-based assessment where students compile evidence of their learning over time, including reflections on their growth. Projects could be assessed based on the quality of thinking demonstrated, the effectiveness of problem-solving approaches, and the sophistication of judgment shown rather than simply correct answers. Some assessment might involve students explicitly using AI tools while demonstrating their ability to evaluate AI outputs, integrate multiple sources, and make independent judgments.

For example, rather than writing a traditional research paper without AI, a student might be asked to use AI to generate an initial literature review, then critically evaluate what the AI produced, identify gaps and errors, conduct additional research, and synthesize a more sophisticated analysis. The assessment focuses on critical evaluation and original synthesis rather than information compilation.

Personalized Learning Pathways

AI enables unprecedented personalization in education, adapting to individual students’ levels, pacing, and learning styles. The new paradigm suggests moving away from lockstep curricula where all students cover the same material at the same pace. Instead, educational institutions might offer more flexible pathways where students demonstrate mastery of competencies rather than accumulating credit hours.

A university might organize education around demonstrated capabilities rather than courses taken. Students could work with AI tutoring systems to build foundational knowledge at their own pace, then engage in projects and seminars that develop advanced skills. Assessment focuses on what students can do rather than which courses they’ve attended. This requires sophisticated tracking systems and careful design to ensure rigor, but AI makes such personalization technically feasible in ways it never was before.

Institutional Examples and Models

Several institutions have begun experimenting with approaches that align with this emerging paradigm, though none has yet achieved a comprehensive transformation.

Arizona State University represents one institution attempting to integrate AI at scale while maintaining educational quality. ASU has partnered with OpenAI to explore how AI tools can support both teaching and learning. Their approach includes using AI for personalized tutoring, adaptive learning systems that adjust to student progress, and tools that help faculty design more effective learning experiences. ASU’s emphasis on scalability and accessibility aligns with the new paradigm’s recognition that AI democratizes access to educational resources. However, the institution still operates largely within traditional structures of courses, credits, and examinations.

Minerva University offers a different model that, while predating widespread AI, anticipates many features of the new paradigm. Minerva eliminates traditional lectures entirely, organizing education around active learning seminars conducted online. Students work through content independently, then engage in small-group discussions focused on developing critical thinking, effective communication, and practical wisdom. Assessment emphasizes demonstration of competencies rather than traditional exams. As AI becomes integrated into their model, Minerva’s structure seems well-suited to emphasizing distinctly human capabilities while leveraging AI for personalized content delivery.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has launched initiatives exploring AI’s role in education through programs like Responsible AI for Social Empowerment and Education (RAISE). MIT recognizes that technical education must prepare students to work alongside AI systems, and this requires not just teaching about AI but fundamentally reconsidering what engineering education should develop. MIT’s studios and project-based learning, particularly in programs like Media Lab, suggest approaches where students tackle complex problems using whatever tools prove helpful, including AI, while faculty focus on developing creative thinking and technical judgment.

Georgia Tech’s Online Master of Science in Computer Science demonstrates how AI-enabled education can scale quality instruction. The program uses AI teaching assistants to handle routine student questions, allowing human instructors to focus on more complex interactions. While the program still operates within traditional degree structures, it shows how AI can augment rather than replace teaching, enabling educational experiences that would be economically impossible with human instructors alone.

Montclair State University in New Jersey has taken a different approach by establishing an AI Across the Curriculum initiative. Rather than treating AI as relevant only to computer science, Montclair is working to integrate AI literacy and tools across all disciplines. Faculty from diverse departments collaborate on developing assignments and projects that thoughtfully incorporate AI while developing critical thinking. This cross-disciplinary approach recognizes that AI’s implications extend far beyond technical fields.

Some K-12 school systems are also experimenting with new approaches. The Summit Learning Program, used in various schools across the United States, employs AI-powered platforms that personalize content delivery while organizing in-person learning around projects, mentoring, and collaborative work. Students progress through content at their own pace using adaptive systems, then apply knowledge in complex projects. Teachers serve as mentors and coaches rather than primarily as content deliverers. While Summit has faced criticism about implementation challenges, it represents an attempt to reimagine schooling around personalization and project-based learning.

Challenges and Concerns

This paradigmatic shift faces significant obstacles. Equity concerns loom large: if education becomes more dependent on AI tools, students without reliable technology access face disadvantages. The new paradigm must include provisions for ensuring all students can access necessary tools and develop relevant capabilities regardless of socioeconomic background. This might require substantial public investment in educational technology infrastructure and careful attention to how AI systems are deployed.

Teacher preparation presents another challenge. Most current teachers and professors were trained in and for the old paradigm. Transitioning to new roles as facilitators, learning designers, and coaches requires extensive professional development. Educational institutions must invest in helping educators understand AI capabilities, develop new pedagogical approaches, and reimagine their professional identities. This represents a massive undertaking that will require years of sustained effort and resources.

Institutional inertia creates perhaps the most formidable obstacle. Universities and school systems are conservative institutions with deeply embedded practices, power structures, and reward systems aligned with the current paradigm. Accreditation bodies, ranking systems, and funding mechanisms all reinforce traditional structures. Faculty promotion decisions often prioritize research over teaching innovation. School accountability measures focus on standardized test scores that reflect old paradigm assumptions. Shifting these institutional features requires coordination across multiple stakeholders and willingness to accept short-term disruption for long-term benefit.

Questions about AI reliability and bias also complicate adoption. AI systems can produce errors, hallucinations, and biased outputs. Educators must help students develop critical awareness of these limitations while using AI productively. This requires that educators themselves understand AI’s technical characteristics and social implications—knowledge that many current practitioners lack.

The Path Forward

Despite these challenges, the trajectory toward a new educational paradigm seems increasingly inevitable. AI’s capabilities will continue expanding, its integration into professional and everyday life will deepen, and the inadequacy of traditional educational structures will become more apparent. The question is not whether education will change, but rather how thoughtfully and equitably that change unfolds.

Educational leaders, policymakers, and practitioners should focus on several priorities. First, experimentation and research are essential. Institutions should create spaces to pilot new approaches, carefully study outcomes, and share learnings. This requires tolerance for failure and recognition that discovering what doesn’t work proves as valuable as identifying successes. Second, collaboration across institutions can help distribute the burden of innovation and ensure that new approaches serve diverse student populations rather than only elite institutions with abundant resources.

Third, policy frameworks must evolve to support rather than constrain innovation. Accreditation systems should recognize alternative approaches to demonstrating educational quality. Funding mechanisms should reward experimentation and outcomes rather than simply maintaining existing structures. Fourth, significant investment in teacher professional development is essential. The paradigm shift succeeds or fails based on whether educators can embrace new roles and develop new capabilities.

Finally, ongoing public dialogue about education’s purposes becomes crucial. The disruption AI creates offers an opportunity to reconsider fundamental questions: What should education develop? How do we know when learning has occurred? What role should educational institutions play in society? These questions lack purely technical answers. They require sustained engagement from educators, students, parents, employers, and citizens.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence presents not merely a new educational technology but a fundamental challenge to the paradigm that has organized formal learning for over a century. The anomalies AI introduces—democratizing expertise, undermining traditional assessment, transforming information literacy, and crossing disciplinary boundaries—cannot be resolved within existing frameworks. They demand a new paradigm that reconceives education’s purposes, transforms curricula and pedagogy, and reimagines the roles of teachers and institutions.

This new paradigm emphasizes developing distinctly human capacities: creative and critical thinking, ethical reasoning, collaborative skills, and metacognitive awareness. It requires curricular shifts toward integration of AI literacy, emphasis on creative synthesis, project-based learning, and reflective practice. Pedagogically, it demands movement from lecturing to facilitating, redesigned assessment, and personalized learning pathways. While institutions like Arizona State University, Minerva University, MIT, and various K-12 schools are exploring aspects of this new paradigm, comprehensive transformation remains largely aspirational.

The challenges are substantial—equity concerns, teacher preparation needs, institutional inertia, and questions about AI reliability all require sustained attention. Yet the trajectory seems clear. Education must evolve to prepare students for a world where AI is ubiquitous, and this evolution requires not incremental reform but paradigmatic transformation. The institutions, educators, and policymakers who engage thoughtfully with this challenge will shape not only schooling’s future but also the development of human capability in an AI-augmented world. The stakes could hardly be higher, for education fundamentally shapes how societies understand themselves and what futures they can imagine.

__________

Prompt: Good morning, Claude. Is AI disrupting our current educational paradigms of learning and development? If yes, how and what are the implications? I’m looking for an essay response of 2,000 to 5,000 words (avoiding bulleted lists) that carefully shows how AI presents anomalies for current paradigms and, thus, requires a new one. For implications, discuss the changes that might be required in school and college curricula and pedagogy. Provide examples of specific institutions that might serve as models.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment