By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Grok)

Editor

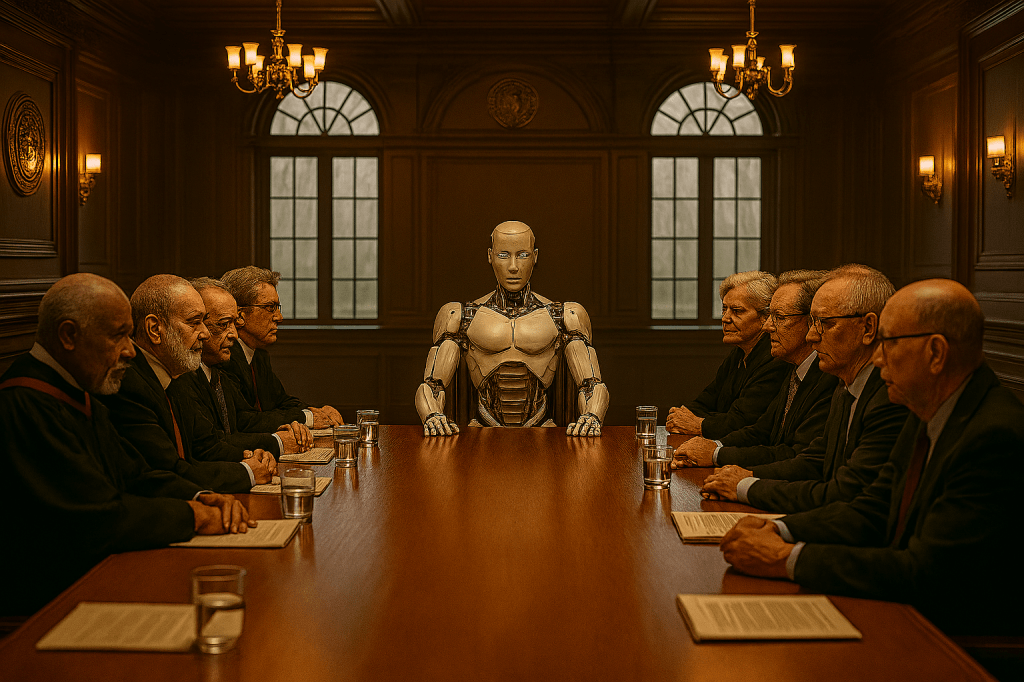

In their 20 October 2025, article published in Times Higher Education, titled “AI threatens universities’ ability to bolster democracy,” Dirk Lindebaum and Gazi Islam present a cautionary argument about the encroachment of artificial intelligence into higher education, framing it as a force that undermines the sector’s role in fostering democratic societies. At the core of their claim is the notion that “Big Edtech”—a term encompassing profit-driven AI companies like those behind ChatGPT and Claude—fuels organizational immaturity within universities, which in turn contributes to broader societal democratic decline.

They portray this as a process where academics and institutions cede epistemic agency, or the control over knowledge production and dissemination, to algorithmic systems, resulting in a homogenized, context-deprived form of knowledge that prioritizes efficiency and commercial interests over critical thinking and civic engagement. To unpack this claim, it is essential to explore how the authors support it through theoretical constructs and illustrative examples, while also assessing its validity against broader scholarly discourse and empirical insights.

Lindebaum and Islam build their argument by first highlighting the rapid integration of AI into higher education, citing institutional adoptions such as the University of Oxford’s provision of ChatGPT access to all staff and students, and Syracuse University’s subscription to Claude for Education. This sets the stage for their prediction that AI will fundamentally alter professional roles: researchers shifting from knowledge producers to mere verifiers of AI-generated outputs, and educators becoming facilitators rather than instructors.

They contend that such reliance leads to outputs dominated by digitally codified information, computational logic, and standardized content, all shaped by the profit motives of private entities rather than the truth-seeking ethos of academia. This marginalization, they argue, erodes the social and civic values universities traditionally uphold, as AI lacks the capacity to engage with human experiences, personal histories, or contextual nuances that underpin deliberative decision-making.

Central to their support is the concept of “organizational immaturity,” a term borrowed from critical theory and elaborated in their co-authored paper published in Organization Studies, which they reference directly. They break this down into three mechanisms: infantilization, where reasoning is outsourced to AI, diminishing human intellectual autonomy; reductionism, substituting nuanced judgment with statistical patterns; and totalization, embedding technology so deeply that education becomes inconceivable without it.

These processes, they assert, shrink the space for critical, original thinking essential not only for a skilled workforce but for an informed citizenry capable of participating in democratic governance. By scaling knowledge in ways that reduce diversity and prioritize efficiency, AI risks enabling monopolistic control over information by tech giants, potentially manipulating public discourse and weakening societal safeguards against authoritarianism or misinformation.

The authors warn that recovery from this immaturity is challenging, as it erodes the very capabilities needed for resistance, and they propose countermeasures like two-stage learning exercises—where students first rely on personal cognition before comparing with AI outputs—and institutional advocacy through independent research centers to reclaim agency.

While Lindebaum and Islam’s framework draws on philosophical traditions, such as Kantian notions of maturity adapted to organizational contexts, their support leans heavily on conceptual reasoning rather than extensive empirical data within the article itself. They allude to the need for scrutiny of AI firms’ marketing claims against evidence, but the piece functions more as an opinionated call to action, grounded in their scholarly work on epistemic governance. This theoretical depth lends credence to their concerns, particularly in light of real-world examples like the proliferation of AI in academic workflows, which could indeed homogenize outputs and sideline tacit knowledge embedded in human experience.

Assessing the validity of these claims reveals a nuanced picture: they are plausible and resonate with a growing body of critiques on AI’s societal impacts, yet they may overstate the inevitability of decline while underplaying potential benefits. On the supportive side, empirical studies align with their warnings about democratic erosion; for instance, research has shown that advancements in AI and information communication technologies over the past decade have hindered democratization in numerous countries by amplifying disinformation and concentrating power.

Similarly, analyses in journals like the Journal of Democracy highlight how generative AI can flood media with misleading content, sowing confusion and undermining trust in institutions, which echoes the authors’ fears of reduced thought diversity and manipulated knowledge. In higher education specifically, the risk of organizational immaturity finds echoes in discussions of surveillance capitalism, where algorithmic systems foster dependency and stifle creativity, potentially weakening universities’ role as bastions of critical inquiry that bolster civic participation.

However, the claims’ validity is tempered by counterarguments that view AI as a tool for enhancement rather than existential threat. Scholars argue that advanced AI systems, while posing challenges like disinformation campaigns that erode institutional trust, also offer opportunities to democratize access to information, facilitate dialogue, and bridge societal divides. For example, AI could empower underrepresented voices in education or streamline verification processes without fully supplanting human judgment, as suggested in reports from organizations like UNESCO, which emphasize ethical frameworks to mitigate risks while harnessing benefits.

Moreover, the link between university AI adoption and societal democratic decline, though intuitively compelling, lacks direct causal evidence in the article; broader studies indicate that AI’s effects on democracy are bidirectional, capable of strengthening participation through tools like civic tech platforms. Lindebaum and Islam’s portrayal risks a deterministic view, assuming unchecked adoption without acknowledging proactive measures already underway, such as AI policies in publishing or regulatory efforts in governance.

Lindebaum and Islam effectively support their claim through a robust theoretical lens that connects AI-driven changes in higher education to organizational immaturity and democratic vulnerabilities, drawing on timely examples and their own research to urge immediate action. Their arguments hold significant validity in highlighting genuine risks, particularly amid empirical findings of AI’s role in hindering global democratization. Yet, the claims’ absolutism overlooks AI’s potential as an ally in education and civic life, suggesting that a more balanced approach—integrating their proposed strategies with innovative uses of technology—could preserve universities’ democratic contributions without succumbing to immaturity or decline.

While Lindebaum and Islam’s argument posits that “Big Edtech” drives organizational immaturity in higher education through mechanisms of infantilization, reductionism, and totalization, ultimately precipitating democratic decline, a robust array of counterclaims emerges from scholarly and practical discourse. These counterarguments suggest that AI, when integrated thoughtfully, can instead democratize knowledge, augment critical thinking, and fortify civic engagement, thereby enhancing rather than eroding universities’ role in supporting democracy.

Far from inevitably leading to epistemic surrender, AI tools offer opportunities for empowerment, provided educators prioritize human agency and ethical frameworks. Lindebaum and Islam’s warnings, while highlighting valid risks, overlook AI’s transformative potential and the proactive strategies already mitigating those dangers.

One of the strongest counterclaims is that AI democratizes access to education and expertise, countering the notion of homogenized, profit-driven knowledge by broadening participation and reducing inequalities that traditionally undermine democratic societies. Rather than marginalizing academics and students, AI platforms enable personalized learning pathways tailored to individual needs, interests, and challenges, allowing learners from diverse backgrounds—regardless of geography, socioeconomic status, or disabilities—to engage with high-quality resources that were once gatekept by elite institutions. For instance, AI-driven adaptive curricula provide real-time feedback and multilingual support, breaking down barriers for English language learners or those in remote areas, thus fostering inclusivity and diffused political participation beyond traditional voting.

This democratization extends to expertise itself, as AI acts as a “zero-cost expert” that levels the playing field, enabling students in under-resourced settings to access sophisticated analyses or simulations that enhance their understanding of complex subjects like policy-making or scientific inquiry. In this view, far from inducing organizational immaturity through over-reliance, AI empowers users to build upon accessible knowledge, promoting a more equitable epistemic landscape that strengthens democratic will-formation by including voices historically excluded from higher education’s civic training.

Moreover, AI actively fosters critical thinking and creativity, directly challenging the claim of reductionism where human judgment is supplanted by statistical patterns. Educational experts argue that AI serves as an imperfect yet resourceful tool that, when paired with pedagogical strategies emphasizing verification and ethical evaluation, cultivates deeper analytical skills rather than diminishing them. By handling routine tasks such as data summarization or initial brainstorming, AI frees students and educators to focus on higher-order processes like synthesis, interpretation, and innovation, thereby stretching the bounds of intellectual exploration.

For example, in classroom settings, students can compare AI-generated outputs with their own work, identifying biases, inaccuracies, or “hallucinations”—fabricated details presented confidently— which hones their ability to cross-reference sources and consider multiple perspectives. This approach not only mitigates infantilization but transforms AI into a catalyst for transformative learning, where learners develop resilience against misinformation, a key democratic competency in an era of digital propaganda.

Empirical findings support this, showing that AI integration leads to improved academic outcomes and engagement, with 80% of teachers reporting enhanced personalized instruction for diverse learners and more time for interactive facilitation. Thus, rather than homogenizing knowledge, AI encourages originality by prompting users to revise and expand upon its outputs, fostering creativity in projects like designing experiments or debating ethical dilemmas.

A further counterclaim addresses the alleged link between AI adoption and democratic decline by highlighting how AI can explicitly boost civic learning and engagement, turning universities into more effective incubators of informed citizenry. Interactive AI tools, such as virtual simulations of political systems or social media analytics platforms, allow students to role-play as policymakers, analyze real-time data on polarization, and detect conspiracy theories, thereby building practical skills in negotiation, digital literacy, and misinformation combat.

These applications promote collaboration through real-time feedback and group discussions on AI-generated content, cultivating empathy and collective problem-solving essential for deliberative democracy. In social studies, for instance, AI generates historical narratives or case studies that educators use to deepen students’ grasp of democratic principles, reducing workloads and enabling more focus on experiential learning. Countering totalization—the embedding of technology to the point of unimaginability without it—proponents emphasize AI literacy as a safeguard, teaching students to critically evaluate tools while blending them with traditional methods like deliberative dialogues and mind mapping.

Universities play a pivotal role here, leading interdisciplinary research to balance AI’s benefits with moral questions, ensuring technology enhances human-centered values and global citizenship rather than eroding them. This proactive stance, as seen in calls for policy reforms and ethical training, prevents the monopolistic manipulation feared by Lindebaum and Islam, instead harnessing AI to reinforce democratic resilience against threats like deepfakes or algorithmic bias.

Critics of the immaturity thesis also point out that AI’s risks—such as perpetuating biases or encouraging dependency—are not inherent but manageable through institutional strategies, rendering the decline narrative overly deterministic. While acknowledging potential for disinformation or over-reliance, research stresses that responsible implementation, including transparency in data use and assignments requiring human-AI comparisons, preserves epistemic agency.

For example, blending AI with pedagogy that prioritizes source verification and ethical reflection equips students to use technology for the common good, countering reductionism by maintaining human oversight. Broader societal analyses reinforce this, noting AI’s compression of knowledge hierarchies democratizes information production, enabling wider participation in discourse and challenging elite control.

In higher education, this translates to more inclusive research environments, where AI accelerates discoveries like new antibiotics while universities safeguard autonomy through balanced approaches. Ultimately, these counterclaims suggest that Big Edtech’s influence is not a zero-sum threat but an opportunity for evolution, where universities reclaim agency by shaping AI’s deployment.

In conclusion, while Lindebaum and Islam rightly urge vigilance against unchecked AI integration, the strongest counterclaims reveal a more optimistic trajectory: AI as an enabler of democratization, critical enhancement, and civic vitality in higher education. By prioritizing literacy, ethical policies, and human-centered design, institutions can avert immaturity and instead amplify their democratic bolstering function, ensuring technology serves societal flourishing rather than subverting it. This balanced perspective, supported by emerging evidence, calls for nuanced adoption over outright resistance, positioning AI as a partner in sustaining vibrant democracies.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment