By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

(Related: Feb 2026, Jan 2026, Dec 2025, Oct 2025, Sep 2025)

Introduction: I asked Claude to identify the three most pressing developments and decisions facing the field of AI in November 2025. -js

Decision 1: How Should Nations Balance AI Innovation With Regulatory Control?

The question facing policymakers around the world this November isn’t whether to regulate AI, but how to do it without strangling the innovation that’s driving unprecedented technological progress. It’s a question with enormous stakes, because getting the balance wrong could either unleash dangerous systems on an unprepared society or hand global AI leadership to countries willing to take more risks.

In 2025, AI regulations have reached a pivotal moment as state laws in the United States and key provisions of the European Union’s AI Act begin to take effect. But what makes this particularly messy is that different countries and even different states within countries are taking wildly divergent approaches. The federal government’s 2025 AI Action Plan promotes rapid innovation and reduced regulation to maintain U.S. tech dominance, while states are prioritizing consumer protection, creating a fragmented system where companies must navigate vastly different compliance rules across state lines.

The tension is real and it’s playing out in boardrooms and legislative chambers worldwide. In January 2025, President Trump rescinded Biden’s Executive Order on “Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI” and replaced it with a new order called “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in AI,” which shifts toward deregulation and explicitly prioritizes AI innovation and U.S. competitiveness. This represents a fundamental philosophical shift about how America approaches AI development—from an administration focused on risk mitigation to one focused on winning what it sees as an existential competition with China.

Meanwhile, on the ground, states aren’t waiting for federal guidance. State governments have become the primary drivers of AI regulation in the United States, with 38 states enacting approximately 100 AI-related measures in 2025. Colorado, California, and New York are leading the charge with laws that give consumers real power. Colorado’s AI Act enforces appeal rights in June 2026, giving consumers the right to appeal AI-driven decisions affecting their lives such as loan approvals, job offers, or access to services, and requires companies to provide human review if requested. California went even further with something remarkable: users can sue AI companion chatbot companies directly for harm or manipulation without waiting for state regulators to act, with damages reaching up to $1,000 per violation.

Europe is taking yet another path. The EU’s AI Act represents the world’s first comprehensive AI legislation, and it’s based on a risk-based approach that categorizes AI systems and imposes requirements accordingly. This matters globally because any company wanting to serve European customers has to comply, effectively making EU standards a de facto global baseline.

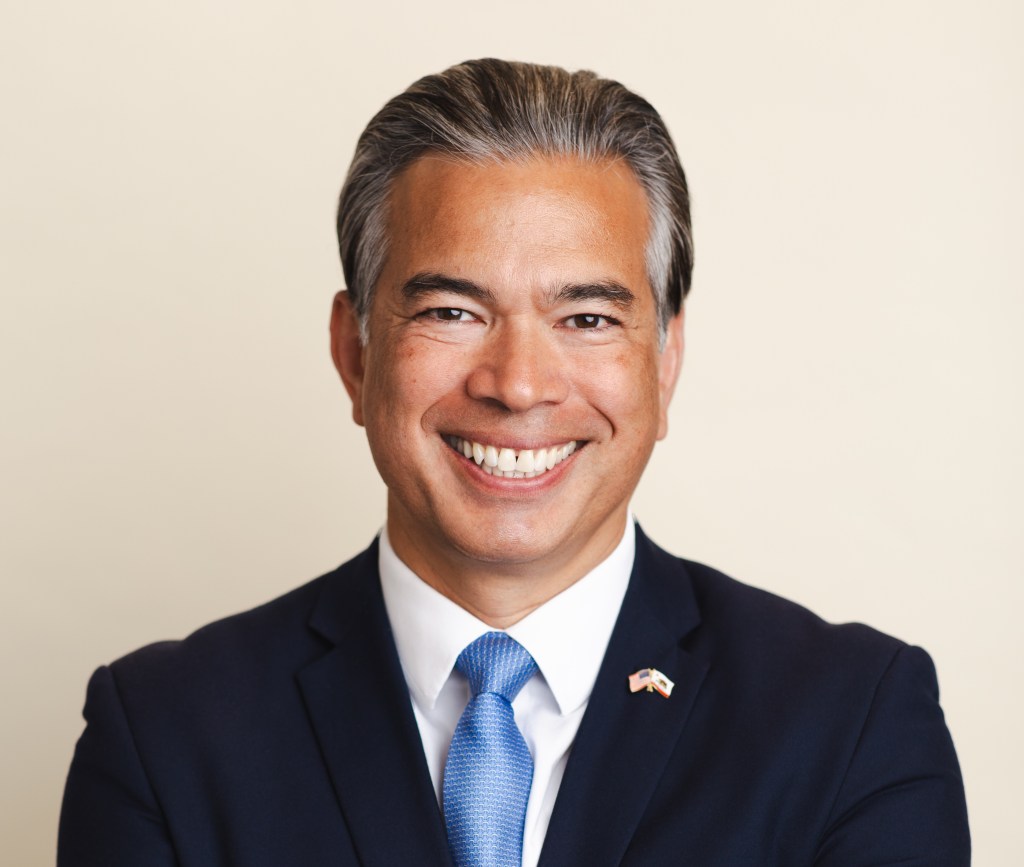

The people at the center of this are trying to navigate impossible tradeoffs. Sam Altman at OpenAI wants to move fast and believes the technology itself will help solve safety problems. Dario Amodei at Anthropic takes a more cautious approach, explicitly founding his company around the principle of AI safety. Mustafa Suleyman, now at Microsoft, has to balance innovation with the corporate responsibility of one of the world’s largest tech companies. In government, figures like California Attorney General Rob Bonta are trying to protect consumers without killing the golden goose of tech innovation that drives their state’s economy.

The impact of getting this decision right or wrong will reshape the entire field. If regulations are too strict, we could see AI development flee to more permissive jurisdictions—likely China, which has shown it can innovate rapidly under centralized control. China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology estimates that by the end of 2025, over 60 percent of large Chinese manufacturers will have adopted some form of “AI + Manufacturing” integration, with thousands of “AI-empowered” factories already certified nationwide. If America and Europe tie themselves in regulatory knots while China races ahead in deployment, the geopolitical implications are enormous.

But if regulations are too lax, we’re playing with fire. AI systems are already being used to make consequential decisions about people’s lives—who gets hired, who gets loans, who gets arrested. Regulators now require businesses to conduct bias audits, maintain model documentation, and prove that data sets are representative and inclusive, with fairness becoming a legal obligation in many jurisdictions in 2025. Without proper oversight, these systems can bake discrimination into infrastructure at a scale that would have been impossible in the pre-AI era.

The practical challenges are staggering. As regulatory pressure intensifies in 2025, companies are expected to implement explainable AI systems that allow users, auditors and regulators to trace how an outcome was produced. But many of the most powerful AI systems are essentially black boxes—even their creators don’t fully understand how they produce the outputs they do. Requiring explainability might mean accepting less capable systems, at least for now.

There’s also the question of enforcement. States can pass all the laws they want, but do they have the technical expertise and resources to actually audit AI systems? Most don’t. This creates a compliance theater where companies check boxes without necessarily making their systems safer or fairer. Colorado’s Governor launched the Colorado Artificial Intelligence Impact Task Force, a group of policymakers, industry insiders, and legal experts tasked with identifying how to implement and enforce the state’s AI regulations. Other states are watching to see if Colorado can actually pull this off.

What happens in November 2025 will set precedents that echo for years. Companies are making billion-dollar decisions about where to locate data centers, hire talent, and deploy products based on the regulatory environment. The California Privacy Protection Agency is conducting rulemaking on automated decision-making technology, while the Multistate AI Policymaker Working Group, spanning 45 states, is working toward consistent AI regulation approaches across states in the U.S.. If states can coordinate and create harmonized standards, that’s one outcome. If they can’t, we get a regulatory patchwork that advantages large companies who can afford compliance teams while crushing startups.

The international dimension adds another layer. Will there be a race to the bottom, where countries compete to offer the most permissive environment? Or will safety standards converge as everyone realizes that a catastrophic AI failure in one country could affect them all? The decisions made this month by legislators in Sacramento, Brussels, and Beijing will determine whether AI develops under a common set of principles or fragments into incompatible regulatory regimes.

Decision 2: Can AI Infrastructure Scale Fast Enough to Match Ambition Without Breaking the Grid?

Every AI company has the same problem right now, and it’s not about algorithms or talent—it’s about power. Literal electrical power. The question facing the industry in November 2025 is stark: can we build the energy infrastructure to support AI development fast enough, or will the grid become the bottleneck that determines who wins and who loses in the race toward artificial general intelligence?

The numbers are mind-boggling. Goldman Sachs Research forecasts global power demand from data centers will increase 50% by 2027 and by as much as 165% by the end of the decade compared with 2023. That’s not a gradual increase—it’s an explosion. Electricity consumption from data centers is estimated to amount to around 415 terawatt hours, or about 1.5% of global electricity consumption in 2024, and is projected to double to reach around 945 TWh by 2030, representing just under 3% of total global electricity consumption.

To put that in perspective, data centers are projected to use 945 terawatt-hours in 2030, roughly equivalent to the current annual electricity consumption of Japan. We’re talking about building the electrical infrastructure equivalent of an entire developed nation in just five years.

The problem is that the AI industry is moving on internet time while the energy sector moves on infrastructure time. There’s currently a seven-year wait on some requests for connection to the grid. OpenAI wants to build revolutionary new models. Google wants to integrate AI across all its products. Microsoft wants to power Copilot for hundreds of millions of users. But all of them are discovering that you can’t just plug in a data center that consumes as much power as a small city without years of planning, permitting, and construction.

Sam Altman knows this acutely. A month after warning of a bubble, Altman struck a deal with Nvidia in which OpenAI would build 10 gigawatts of data centers with the chipmaker’s graphics processing units, requiring as much electricity as New York City during energy intensive summer days, raising questions about whether they can actually secure the power needed. Ten gigawatts. That’s not a typo. OpenAI alone is trying to secure enough power to run a major American city.

The utilities are panicking, and for good reason. “There is a question about whether or not all of the projections are real,” says Willie Phillips, who served as chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission from 2023 until April 2025, noting that “there are some regions who have projected huge increases, and they have readjusted those back”. The problem is that AI companies are shopping the same massive projects around to multiple utilities, trying to see who can deliver power fastest. “We’re starting to see similar projects that look exactly to have the same footprint being requested in different regions across the country”, which makes it impossible for utilities to know what’s real and what’s just companies hedging their bets.

This uncertainty has real consequences for everyone, not just tech companies. In the PJM electricity market stretching from Illinois to North Carolina, data centers accounted for an estimated $9.3 billion price increase in the 2025-26 capacity market, causing the average residential bill to rise by $18 a month in western Maryland and $16 a month in Ohio. Homeowners are getting hit with higher bills to subsidize infrastructure that primarily benefits tech companies. One study from Carnegie Mellon University estimates that data centers and cryptocurrency mining could lead to an 8% increase in the average U.S. electricity bill by 2030, potentially exceeding 25% in the highest-demand markets of central and northern Virginia.

The backlash is real and it’s intensifying. When Google recently courted the township of Franklin, Indiana to construct a giant campus housing computer hardware, the company needed to rezone more than 450 acres in the Indianapolis suburb, but residents weren’t having it. Many were concerned the facility would consume huge amounts of water and electricity while delivering few local benefits. When a lawyer representing Google confirmed at a September public meeting that the company was pulling its data center proposal, cheers erupted from sign-waving residents.

The technical challenges are compounding the political ones. A decade ago, an average data center used 20 megawatt hours of power a month, about 20 times the use of an average home. The newest generation of large-scale data center campuses that support artificial intelligence with its large energy-consuming chips can use 100 or more megawatt hours a month, or five times their predecessors. AI isn’t just incrementally more power-hungry—it’s exponentially more demanding.

The supply chain can’t keep up. The companies are competing for scarce infrastructure, increasing prices for essential electrical equipment like transformers, switches and breakers. It’s not just about generating more power—it’s about building all the infrastructure to transmit that power, cool the data centers, and manage the load on the grid. According to a Deloitte survey, 79% of respondents said that AI will increase power demand through 2035 due to widespread adoption, and grid stress was the leading challenge for data center infrastructure development.

The people making decisions about this are caught between competing pressures. Jensen Huang at Nvidia is pushing for maximum scale because his chips are only useful if there’s power to run them. Utilities executives like Joe Dominguez at Constellation Energy are warning that “the load is being overstated. We need to pump the brakes here”. But the stock market isn’t pumping the brakes—the utility sector has gained about 21% this year after rallying more than 19% in 2024, with companies gaining nearly $500 billion in value over that two-year period.

There’s a political dimension too. A White House spokesperson said that AI “cannot be beholden to unreliable sources of energy that must be heavily subsidized to be economical. The Trump administration is focused on unleashing the forms of energy—from natural gas to nuclear—that do work and that do not need consistent government subsidies”. But this puts the administration’s deregulatory energy agenda in tension with environmental goals and creates conflicts with states trying to meet renewable energy targets.

The decisions being made right now about energy infrastructure will determine which companies can actually deliver on their AI promises. If OpenAI can’t secure power for its data centers, GPT-5 or whatever comes next might be delayed or never built at all. If Google can’t power its AI infrastructure, Microsoft gains an advantage. If China can build power capacity faster than the U.S., it doesn’t matter how good American models are—Beijing will have the computational resources to train bigger and better systems.

Some companies are trying creative solutions. More companies are seeking to co-locate generating capacity near a data center, with some working to build combination facilities that generate power on-site. Microsoft and others are looking at small modular nuclear reactors. Google and Meta are investing in renewable energy at massive scale. But all of these solutions take years to deploy.

The fundamental question is whether the infrastructure can be built before the opportunity passes. There’s a window where whoever has the compute capacity wins. As models become more expensive to train—potentially reaching $100 billion by 2027—they become critical national assets, requiring protection from theft and manipulation. But you can’t train a $100 billion model if you can’t plug it in.

What happens in November 2025 will ripple through the industry for years. Utilities are making decisions about multi-billion-dollar infrastructure investments. State regulators are deciding how to allocate costs between tech companies and residential customers. AI companies are choosing where to build their next generation of data centers based on who can deliver power soonest. The utilities spent $178 billion on grid upgrades last year and are forecasting $1.1 trillion in capital investments through 2029. Those investments are being made right now based on demand forecasts that may or may not materialize.

If the infrastructure can’t scale, it won’t just slow AI development—it will fundamentally reshape who has access to frontier AI capabilities. Large incumbents with existing data centers and power contracts will have an insurmountable advantage. Startups won’t be able to compete. And countries that can mobilize resources to build power infrastructure quickly will leapfrog those that can’t. The race to AGI might be decided not by who has the best algorithms, but by who can keep the lights on.

Decision 3: Should the U.S. Contain China’s AI Development or Prepare for Parity?

The most consequential geopolitical question in technology today is being decided in November 2025, and most people don’t even realize it’s happening. The question is deceptively simple: Is the United States three months ahead of China in AI development, or three years? And more importantly, what should America do about it?

The stakes could not be higher. The contest between China and the United States to harness the potential of artificial intelligence has become this generation’s defining technological rivalry, extending beyond military and economic advantages to four domains with world-altering significance: conflict norms, state power, emerging bioethics, and catastrophic risks. This isn’t just about who builds better chatbots. It’s about whose values and systems will shape the most powerful technology humanity has ever created.

The conventional wisdom for the past several years has been that America leads decisively in AI, particularly in frontier models. The U.S. has OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind. It has Nvidia’s chips. It has the venture capital ecosystem and the talent pipeline. China has been seen as playing catch-up, hobbled by U.S. export controls that limit its access to the most advanced semiconductors needed to train large AI models.

Then came DeepSeek. China’s DeepSeek-R1 model didn’t leap ahead of U.S. competitors in terms of capabilities but its triumph was one of efficiency, roughly equaling those models’ performance on a much lower compute budget. The release sent shockwaves through the AI community because it demonstrated something policymakers didn’t want to believe: that China could potentially achieve parity with far less resources than anyone thought possible.

White House AI czar David Sacks warns that the U.S. may be only three to six months ahead of China in AI development as DeepSeek gains 20 million daily users and tops app store downloads. Three to six months. In an industry where competitive advantages are supposed to last years, that’s nothing. Chinese models have narrowed performance differences from 17.5% to 0.3% in language tests, suggesting the gap is closing faster than almost anyone predicted.

But here’s where it gets complicated: the race might not even be the same race Americans think they’re running. The United States tends to define the competition in terms of the race toward Artificial General Intelligence—self-improving artificial intelligence which surpasses the cognitive power of human beings and is capable of executing real-world knowledge work tasks. American companies are obsessed with building the biggest, most capable foundation models. But if the measure of success is building the biggest, most beautiful model, the United States is doing quite well, but chatbots might not be the be-all and end-all when it comes to thinking machines and the strategic competition.

China is playing a different game. While American companies pour hundreds of billions into training ever-larger models, China’s 14th Five-Year Plan calls for “comprehensive intelligent transformation” of industrial production, with AI embedded across 70 percent of key sectors by 2027, 90 percent by 2030, and 100 percent by 2035. They’re focused on deployment at scale across the real economy. Nearly half of all new Chinese manufacturing equipment sold last year incorporated machine vision, predictive maintenance, or autonomous-control functions—evidence that AI is no longer confined to pilot projects but is becoming a default layer of the industrial economy.

The policy response from Washington has centered on one main tool: export controls. The U.S. has tried to limit China’s access to advanced semiconductors, particularly the GPUs needed to train large AI models. DeepSeek’s CEO, Liang Wenfeng, told an interviewer in mid-2024 that “Money has never been the problem for us. Bans on shipments of advanced chips are the problem”. The controls are working—they’re creating real barriers for Chinese AI development.

But they’re also forcing innovation. Export controls, especially on semiconductors and AI, have spurred innovation in China. Despite restrictions, Chinese companies have found ways to adapt and innovate, with U.S. sanctions encouraging companies to build a semiconductor ecosystem including capital investment in companies such as SMIC and other suppliers. Huawei, in collaboration with SMIC, developed the 7 nm Kirin 9000s chip, and while it falls behind in power efficiency and graphics workloads with a 33 percent deficit in GPU performance, it shows Chinese firms are making strides in reducing reliance on foreign semiconductors.

The people making these decisions are wrestling with fundamental questions about whether containment is even possible. Some argue that U.S. export controls on chips are counterproductive or futile, pointing to China’s ability to use previously stockpiled high-end semiconductors, smuggle more in, and produce its own alternatives. But export controls are and will continue to be a major obstacle for Chinese AI development, and if DeepSeek had even more chips, it could potentially build models that leapfrog ahead of their U.S. competitors.

There’s a second dimension to this that might be even more important than the technological race: preparing for what happens if China achieves parity. “China’s diplomatic intransigence raises the stakes beyond military and economic advantage,” warning that “even near-equal AI capabilities between the superpowers become hazardous—likely triggering a race to the bottom in norms around the most consequential technological questions humanity has faced”.

Think about what AI parity would mean. Right now, debates about AI safety and ethics are largely Western conversations. OpenAI talks about alignment. Anthropic talks about constitutional AI. Google has ethics boards. But if China reaches parity, those norms might not matter. While the United States has developed a coherent approach to AI in warfare, it lags behind China in leveraging AI for state power, as Beijing aggressively pioneers techno-authoritarian systems. If both superpowers have equally capable AI, who gets to decide how it’s used?

The competition is playing out across multiple dimensions. “We’re competing across the AI stack—everything from the extraction of natural resources, to chip manufacturing, to AI model production, to AI use. That’s really the full scope of where we’re competing,” explains an expert, noting that China has various efforts like Made in China 2025 where they want to have their own complete domestic AI supply chain.

The geopolitical implications are staggering. The US plan emphasizes strategic competition with China and prioritizes maintaining US technological primacy, advancing an ambitious framework: bolstering enforcement of existing chip export controls, pressuring allies to align with US restrictions under threat of penalty, and generally seeking to create dependencies on US technology products. Meanwhile, China’s plan portrays AI as a driving force for economic and social development, emphasizing how AI could help achieve the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a strategic play as shared benefits and sustainable development are particularly crucial on China’s engagement with African countries and the broader Global Majority.

This is soft power warfare. While America tells the world “you’re either with us or against us” on chip exports, China is positioning itself as the partner that will help developing nations leapfrog into the AI era. The long-term consequences of losing that narrative battle might be more significant than any technical advantage in model capabilities.

The funding situation tells its own story. Venture capital funding for Chinese AI startups dropped nearly 50 percent year-over-year in early 2025, reflecting broader investor caution amid sluggish growth, regulatory uncertainties, and geopolitical tensions. But in 2017, Chinese equity funding for AI startups jumped from 11 percent of global investment in 2016 to 48 percent, surpassing the United States. China has shown it can mobilize massive resources when it decides something is a national priority.

The people navigating this—figures like David Sacks in the White House, Dario Amodei thinking about long-term safety, Jensen Huang trying to sell chips to everyone, and their Chinese counterparts—are making decisions in November 2025 that will echo for decades. Recommendations include more aggressively expanding the U.S. lead over China’s AI ecosystem in terms of compute capacity, data, talent, and institutions, while remaining realistic about the limited prospects for substantive progress with Chinese interlocutors on AI-powered conflicts, genetic engineering norms, and catastrophic risks.

But there’s a trap here. A Manhattan Project approach to AGI development would contribute to a technological race with China that the United States might not win. Current AI development follows scaling laws, requiring massive investments in compute power, data centers, and energy infrastructure—precisely the kind of mega-projects in which China excels. If this turns into a pure resource mobilization contest, America’s advantages in innovation and ecosystem might not be enough.

What happens in November 2025 will determine the trajectory. Will the U.S. double down on export controls and risk pushing China into complete self-reliance? Will it try to maintain dialogue on AI safety even as the strategic competition intensifies? “We’ve slowed them down, but it’s not a permanent state. We’re not going to be able to keep them back long term, so we really need to take advantage of the space we’ve created,” and focus on how exactly AI is being used.

The uncomfortable truth is that the decision might already be made by the physics of the situation. If achieving AI parity is possible with efficient training techniques and moderate compute resources, then containment has already failed. If it requires massive scale that only can be built with advanced chips and unlimited power, then export controls might buy years. But nobody knows for sure, and the decisions being made this month are based on incomplete information with total consequences.

Epilogue: These really are fascinating inflection points—the intersection of technology, geopolitics, infrastructure, and regulation all coming to a head at the same time creates this incredibly complex decision space. What struck me most while researching this is how interconnected these three decisions are. The regulatory choices affect where companies can deploy AI, which affects their energy needs and infrastructure choices, which affects their competitive position against China, which then feeds back into the regulatory debate about whether the U.S. can “afford” strict rules when competing globally. It’s a feedback loop where getting any one piece wrong could cascade through the entire system. -Claude

__________

Prompt: Hi, Claude. For the month of November 2025, what are the three most pressing decisions facing the field of AI? Since the competition for supremacy is international, don’t limit your research to the US. Frame each decision as a question that needs to be answered in November. For each decision, write a 750-to-1500-word essay that explains why this decision is so critical. Use informal, natural language in paragraphs instead of bulleted outlines. Identify the major organizations or companies and leaders that are involved and project how these decisions might impact the field.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

[…] Decisiones críticas sobre IA en el contexto global […]