By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude & ChatGPT)

Editor

Introduction: I asked Claude to report on articles published in 2025 that discuss why banning AI chatbots is impossible or unwise in college settings. It found four. I also asked ChatGPT to add two more. -js

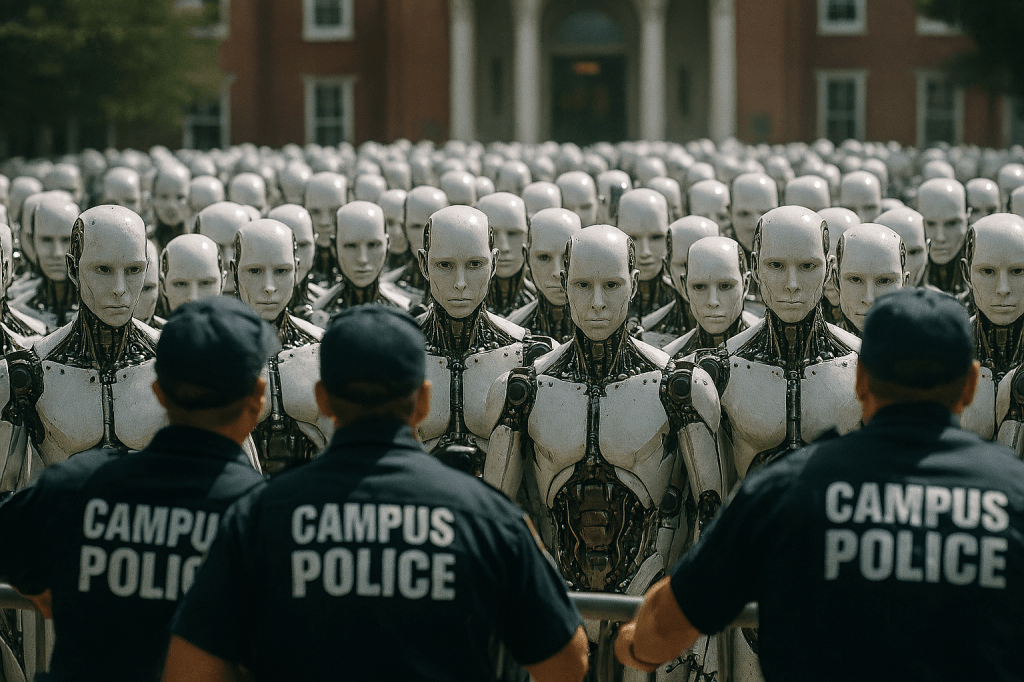

Several articles published in 2025 have examined the practical impossibility and pedagogical folly of attempting to ban AI chatbots from college campuses. Unlike previous technological disruptions such as calculators or laptops, which could be restricted through institutional policy and physical control, chatbots present an enforcement challenge that many educators now consider insurmountable.

In a 12 Sep. 2025 article for Fortune, education reporter Jocelyn Gecker documented the widespread shift away from prohibition-based approaches to AI in higher education. The piece, “ChatGPT bans evolve into ‘AI literacy’ as colleges scramble to answer the question: ‘what is cheating?'” chronicles how initial panic has given way to pragmatic acceptance. Gecker reported that Carnegie Mellon University’s faculty had been explicitly told that “a blanket ban on AI ‘is not a viable policy’ unless instructors make changes to the way they teach and assess students” (Fortune). The article features Valencia High School student Jolie Lahey, who captured the generational divide perfectly when she described strict no-AI policies in these terms: “It’s such a helpful tool. And if we’re not allowed to use it that just doesn’t make sense. It feels outdated.” The ubiquity of AI access makes enforcement essentially impossible, particularly since students can use the technology outside the classroom on personal devices and home networks.

Writing for eCampus News on 29 May 2025, Kelly Dore of Acuity Insights addressed the specific impossibility of controlling AI use in college admissions. In “Universities can’t block AI use in applications—but they can ensure fairness,” Dore presented survey data showing that 74 percent of applicants believe they should be able to use AI during the application process to some extent, while simultaneously acknowledging that 69 percent believe AI gives certain applicants an unfair advantage. Most tellingly, Dore noted that 82 percent of applicants believe their peers will continue using AI regardless of institutional policies. The article’s central argument is captured in Dore’s observation that schools cannot ban AI outright, writing that applicants don’t believe that AI tools should be banned entirely (or that schools would even be able to do so) (eCampus). Rather than pursuing futile prohibition, Dore urged universities to develop clear guidelines that extend from application through graduation.

On 13 May 2025, The Hechinger Report published Kelsey Behringer‘s opinion piece “Instead of punishing students for using AI, colleges and universities must provide clear, consistent guidelines and rules,” which used the case of Haishan Yang, a doctoral student expelled from the University of Minnesota over alleged AI use, to illustrate the dangers of punitive approaches lacking institutional clarity. Behringer argued that institutions that expel students for using AI are likely punishing themselves in the long run (Hechinger) particularly given that employers increasingly expect AI literacy from college graduates. Behringer emphasized the economic imperative facing universities, noting that with higher education teetering on the edge of an enrollment cliff, colleges and universities should embrace AI or risk losing students and scholars to institutions taking a more proactive view of these transformative technologies. The article underscored that creating an “AI-forward campus” means embracing rather than banning the technology, as research demonstrates substantial benefits for higher education when AI is integrated thoughtfully.

Perhaps the most philosophically rich treatment of this issue came from Catherine Savini of Westfield State University, who published “We Can’t Ban Generative AI, but We Can Friction Fix It” in Inside Higher Ed on 16 July 2025. Savini, a writing across the curriculum coordinator, opened with a frank admission that has become a refrain among educators: faculty ask me how to detect their students’ use of generative AI and how to prevent it. My response to both questions is that we can’t (Inside Higher Education). Savini’s analysis went beyond the simple observation that bans are unenforceable, arguing that the integration of AI into familiar tools like Microsoft Word and Google Docs has made it increasingly difficult to avoid AI entirely. She noted that when faculty ask her about detection and prevention of AI use, her consistent answer remains the same—that such control is simply impossible. Rather than pursuing prohibition, Savini advocated for “friction fixing,” making AI harder to use thoughtlessly while making genuine engagement with writing assignments easier and more compelling.

These articles converge on several key arguments for why banning chatbots differs fundamentally from restricting earlier technologies. First, access is universal and uncontrollable—students carry AI-enabled devices everywhere and can access chatbots through countless platforms and interfaces. Second, detection is unreliable at best and discriminatory at worst, with AI-detection software showing documented bias against non-native English speakers and neurodivergent students. Third, bans run counter to workforce preparation, as employers increasingly expect college graduates to demonstrate AI literacy and competency. Fourth, the sheer prevalence of student use means that enforcement would require investigating vast numbers of students, creating an adversarial rather than educational atmosphere.

The consensus emerging from these 2025 articles is not merely that bans are difficult to enforce, but that they represent a fundamental misunderstanding of higher education’s role in preparing students for a world in which AI is already ubiquitous. Rather than waging what one early commentator called an unwinnable “arms race between digitally fluent teenagers and their educators” (Duckworth & Ungar, 23 Jan. 2023), institutions are being urged to channel their energy into teaching responsible use, critical evaluation, and ethical engagement with these powerful tools. The question has shifted from whether to allow AI to how to integrate it meaningfully while preserving the intellectual rigor and authentic learning that remain higher education’s core purposes.

ChatGPT

James D. Walsh’s 7 May 2025 essay in New York Magazine’s Intelligencer, “Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College,” documents the social reality that students are already habitually using chatbots across campuses and that administrators have been “stymied” in attempts to enforce bans. Walsh reports that many institutions reverted to ad-hoc, professor-by-professor approaches because there simply was no plausible way to enforce an all-out ChatGPT ban — students access multiple chatbots, use them off-network and through integrated apps, and learn to disguise AI-authored prose. The value of Walsh’s reporting is that it grounds the “futility” argument in student behavior and marketplace realities rather than abstract policy: when an educational technology is convenient, widely available, and useful, technical blocks are easily circumvented. (New York Magazine)

A 20 June 2025 set of Chronicle of Higher Education pieces and features, including a May 23 reflection by a faculty member on serving an AI committee and a June 20 feature “These Students Use AI a Lot — but Not to Cheat” by Beth McMurtrie, repeatedly invoke the calculator analogy and then complicate it. The commentary notes that while calculators once faced resistance, LLMs are more pervasive and intimate: they are integrated into workflows, substitute for scaffolding that some students lack, and, crucially, reshape what “doing the work” means. The Chronicle coverage argues that technical bans ignore these pedagogical and equity dimensions, and that treating chatbots as simply another banned device underestimates their pervasiveness and potential educational roles. (The Chronicle of Higher Education+1)

Taken together, these 2025 pieces propose several overlapping reasons why banning chatbots on campuses is likely futile or foolish. First, technical futility: generative models are now embedded into mainstream writing and productivity software and are reachable off-network, so blocking one domain or IP addresses only drives students to equivalent services or to local tools. Second, behavioral reality: students who find AI useful for time management, study scaffolding, or overcoming language and learning barriers will find ways to use it — and inconsistent enforcement (professor by professor, course by course) invites confusion and cynicism.

Third, pedagogical cost: banning can push educators toward in-class, timed assessments that, while “AI-proof,” can disproportionately harm students with disabilities, non-native speakers, or those who rely on revision as a learning process. Fourth, legal and fairness risks: punitive enforcement without clear, consistent policies and reliable detection can produce miscarriages of justice and reputational harm. Finally, opportunity cost: wholesale bans close off an urgent pedagogical conversation about AI literacy, equity, and how to teach students to use these tools responsibly in workplaces that will expect such competence. (The Chronicle of Higher Education+3Inside Higher Ed+3New York Magazine+3)

None of these authors suggests that challenges vanish or that all uses of chatbots are benign. Rather, the consensus in 2025 reporting and commentary is pragmatic: colleges should stop treating the problem as one of policing access and instead treat it as a curricular and institutional design problem — teach students when and how AI assistance is acceptable, redesign assignments to emphasize process and authentic demonstration of learning, and focus enforcement where misuse is demonstrably harmful. In short, many 2025 voices argued that trying to build an impenetrable wall around campus writing or learning is anachronistic; thinking constructively about pedagogy, equity, and technology policy is the wiser, if harder, path. (Inside Higher Ed+2The Hechinger Report+2)

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment