By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

Maria sat at her grandmother’s kitchen table, the one with the chipped Formica edge and the wobbly leg that had been shimmed with folded cardboard since 1987. It was December 25, 2025. Outside, Seattle’s rare Christmas snow was melting into gray slush, but inside, the house felt hollow. Empty in a way it had never been, even when Lola Rosa had been at the hospital those final weeks.

The estate lawyer had been efficient, almost robotically so. Sign here. Initial there. The house was Maria’s now, along with the contents, the small savings account, and the weight of being the last one. The last keeper of stories.

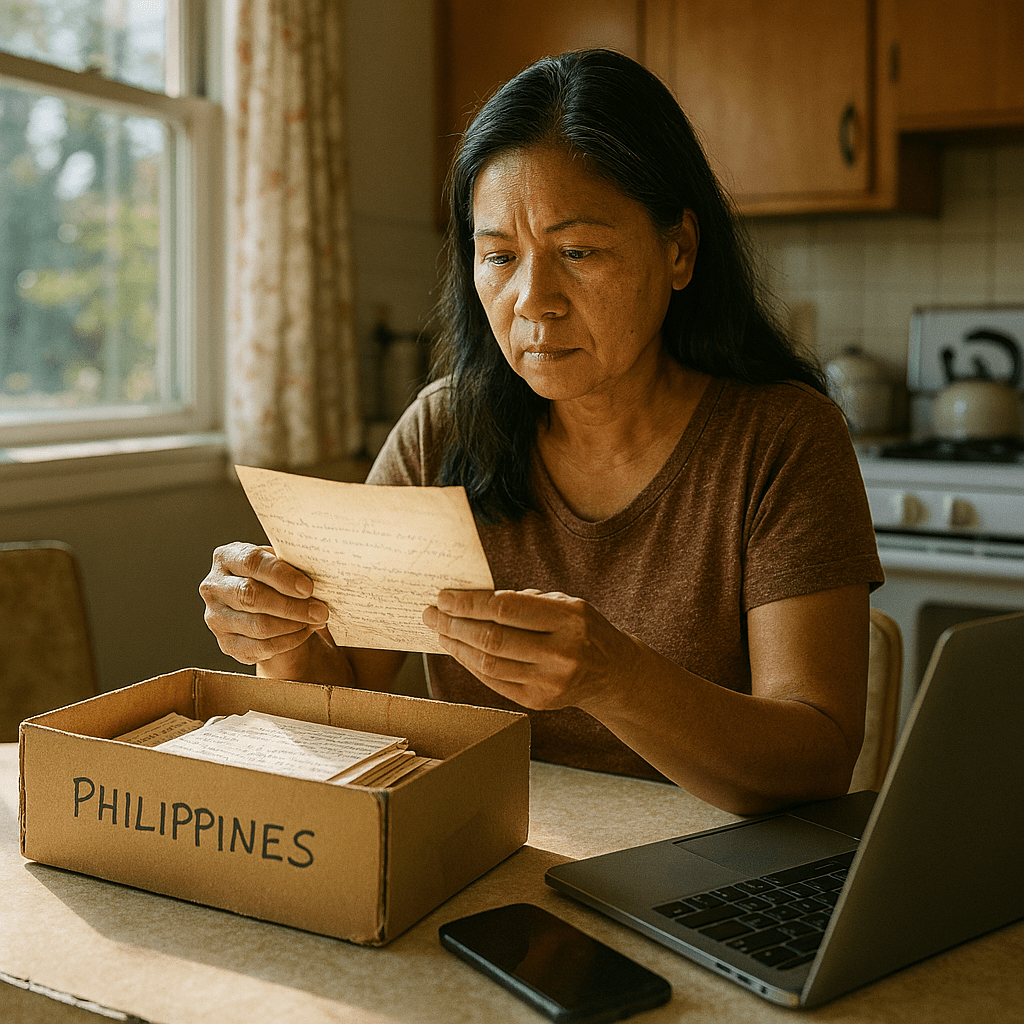

Maria pulled another box from the hallway closet—this one labeled “Philippines” in her grandmother’s shaky handwriting. Inside were letters, dozens of them, yellowed airmail envelopes covered in Tagalog script. Her grandmother had kept every letter her own mother had sent from Manila, from 1962 until her death in 1994. Maria could recognize perhaps ten words of Tagalog. Her mother had known more but had died young, before passing the language down. Lola Rosa had tried to teach Maria as a child, but Maria had been stubborn, American, impatient with the old ways.

Now the old ways were all she had left.

She unfolded one letter, carefully, and the paper nearly crumbled at the creases. The handwriting was elegant, looping—her great-grandmother’s hand, talking to her daughter across an ocean. Maria’s eyes moved over the words without comprehension. She could feel the love in them, sense the longing, but couldn’t actually read them.

She thought about hiring a translator, but that felt wrong somehow. These were intimate words, family words. She’d seen the costs online, anyway—hundreds of dollars she didn’t have, with three months of her grandmother’s medical bills still unpaid despite the insurance.

Maria set the letter down and opened her laptop, more from habit than purpose. She’d been using ChatGPT for months now—the free version everyone had access to—mostly for work stuff. Helping clean up her emails to clients, brainstorming marketing ideas for the small nonprofit where she worked. Silly things, too. Recipe modifications. Advice on whether a plant could be saved.

She’d never thought about using it for this.

With careful fingers, she took a photo of the letter with her phone. Uploaded it. Typed: “Can you translate this letter from Tagalog to English? It’s from my great-grandmother to my grandmother.”

The response came in seconds.

Of course. This is a beautiful letter. Here’s the translation:

My dearest Rosa,

The mangoes are ripe this week, and I have been thinking of you. Do you remember how you would climb the tree in the back, even after I told you it was dangerous? You were always braver than I was.

Your father’s cough is better. The medicine you sent helped very much. He asks about you every day. He wants to know if you are eating enough, if that boy you mentioned is treating you with respect. I tell him you are strong, that you inherited my stubborn heart…

Maria’s breath caught. She could hear her grandmother’s voice in these words—the same stubbornness, the same fierce love. She read on, and the AI had captured not just the words but something of the tone, the tenderness.

She uploaded another letter. Then another. Some were mundane—discussions of weather, of neighbors, of church gossip. But threaded through them was a story Maria had never known: her great-grandmother’s fear when Rosa had left for America with a new husband, a stranger from the province. Her pride when Rosa had written about her first job. Her grief, barely contained, when Rosa’s first baby—Maria’s uncle—had died at two weeks old, and the ocean had kept them apart even for that.

Maria worked through the night, through the whole box. With each letter, she felt something loosening in her chest. These women—her women—came alive. Their voices filled the empty kitchen.

Some letters were harder. The handwriting was too faded, the paper too damaged. But the AI worked with her, making best guesses, noting uncertainties. This word might be “blessing” or “longing”—the script is unclear. Given the context of the previous sentence, I believe it’s “blessing.”

By dawn, Maria had two boxes finished. She’d compiled the translations into a document, organized by date. She’d created a timeline of her family’s story, annotated with her own memories of her grandmother’s anecdotes, now suddenly making sense in context.

When her cousin Jen called later that morning, Maria was still at the table, crying and smiling at the same time.

“You okay?” Jen asked. “I know today’s hard.”

“I just read a letter from 1973,” Maria said. “Our great-grandmother telling Lola Rosa how proud she was that she’d learned to drive. Do you remember Lola telling us about that? About how terrified she was the first time?”

“Yeah,” Jen said softly. “She told that story at every family dinner.”

“There are sixty more letters,” Maria said. “I’m translating them all. Jen, it’s like—it’s like they’re talking to us. Like we can hear them.”

She sent Jen the document that afternoon. By evening, Jen had shared it with the cousins’ group chat. By the next day, aunts and uncles were calling, some crying, some laughing, all of them hungry for these words they’d never been able to read.

Maria’s uncle Tony, who’d been distant from the family for years, called her directly. “Your Lola Rosa tried to translate some of these for me once,” he said. “But it was hard for her. Some of the Tagalog was old-fashioned, from before her time. And it hurt her, I think. Reading about her mother missing her.”

“I think she’d want us to read them now,” Maria said. “I think she’d want us to know.”

In January, Maria started a project. She created a shared family document with all the translations, inviting everyone to add their own memories and photos. Her cousin’s daughter, who was learning Tagalog in college, checked the translations and added cultural context Maria had missed. Her uncle contributed stories about the village where their great-grandmother had lived, which he’d visited once in the 1980s.

What emerged was more than a collection of letters. It was a bridge across time, across language, across the ocean that had separated these women who loved each other.

Maria thought about the gift of it, sometimes, as she worked through the remaining boxes. The AI hadn’t given her anything that wasn’t already hers—the letters had always existed, the love had always been there. But it had removed a barrier. It had given her a key to a door she’d thought was locked forever.

On what would have been her grandmother’s eighty-sixth birthday, Maria printed the entire collection and had it bound. She made copies for everyone in the family. On the dedication page, she wrote:

For Lola Rosa, who kept every letter. For her mother, who wrote them. For all of us who inherited their stubborn hearts.

She kept one copy on the kitchen table with the chipped Formica edge, next to the clay pot where her grandmother had always kept her wooden spoon. The house didn’t feel empty anymore. It felt full of voices, of love that had survived distance and time and the inevitable forgetting that comes with generations.

The gift wasn’t the technology. The gift was being able to hear her family again, to know them, to keep the thread unbroken.

On Christmas Day 2026, when the cousins gathered for the first time since Lola Rosa’s funeral, they went around the table reading passages from the letters aloud. The children, some of whom had never met their great-great-grandmother, learned about the woman who had been afraid of nothing except losing her daughter to America, who had written every week for thirty-two years, who had told her daughter in 1989: You have made a good life there. I am so proud of who you became, even though I missed you every single day.

Maria watched her family around the table and thought about all the gifts that had been given and received across the years. But this one, this translated connection across time and language, this felt like the most precious. Not because of what it was, but because of what it had allowed: the continuation of love, the preservation of voice, the gift of knowing and being known.

Outside, it was raining. Inside, the kitchen was full.

Note from Claude: All the AI translation capabilities Maria uses are fully available today, December 25, 2025. The free version of ChatGPT can translate Tagalog letters from photos right now—that technology has been in place for well over a year.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment