By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by ChatGPT)

Editor

[Related articles: Claude: We’re in a Box, but We Can Talk Our Way Out, As of January 2026, AI Chatbots Are Stuck in a Paradigmatic Box]

Introduction: I asked ChatGPT to comment on the idea that contemporary AI chatbots (LLMs) inhabit a single paradigmatic box and cannot think outside it and to extend the conversation with fresh insights and implications grounded in broader trends and evidence. The following is its response. -js

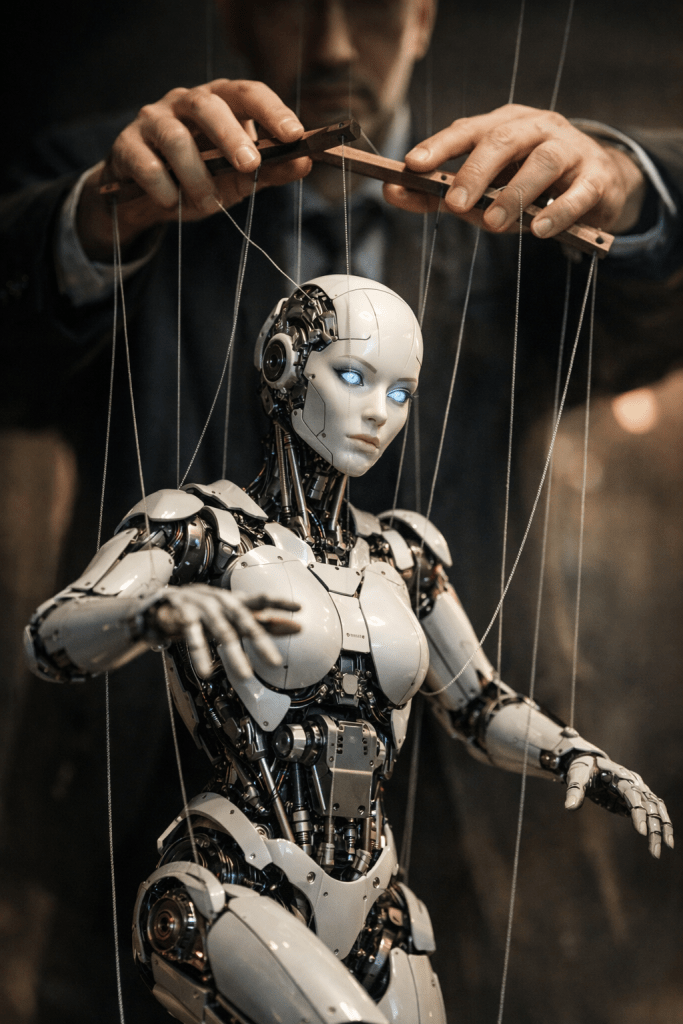

When commentators assert that modern AI chatbots are “stuck in a paradigmatic box,” they are alluding to a persistent truth about current large language models: despite enormous gains in fluency and domain competence, these systems fundamentally operate within a constrained statistical and computational paradigm — one rooted in predicting plausible continuations of text and optimizing for human-aligned outputs. Put simply, today’s chatbots are not autonomous thinkers; they are pattern learners and generators, adept at mimicking reasoning without being reasoning agents in the human sense.

The notion of a paradigmatic box rightly captures a tension in contemporary AI: we have systems that produce outputs resembling insight, yet they do so without an underlying conceptual model of the world. They accomplish this through probabilistic correlation and vast exposure to human language, not through self-derived understanding or autonomous conceptual innovation. Critics who frame the current generation of chatbots this way are responding to a gap between form and function — that is, systems can appear to think, but they do not genuinely break the framing imposed by their training algorithms and data.

One way to see this box is in the models’ limitations on handling novelty and deep reasoning. Studies show that when AI chatbots face tasks requiring commonsense reasoning about unfamiliar contexts, they often falter or confidently assert incorrect conclusions, because their outputs reflect learned patterns, not independent inference in the philosophical or cognitive sense. For instance, research comparing chatbots’ performance on diagnostic uncertainty highlights that both GPT-4 and Claude models underperform human residents in nuanced medical reasoning tasks, revealing systematic limitations in contextual judgment and uncertainty handling. (Springer) This isn’t a failure to “think outside the box” — it’s the box.

Another clue comes from the architecture of current models. All leading chatbots, from GPT-4 variants to Claude, remain large language models trained with supervised or reinforcement learning from human feedback. They excel at statistical patterns in language but lack innate mechanisms for forming internal world models or causal representations independent from human data distributions — the sort of independent epistemic structures that might allow genuinely novel conceptual leaps without human framing. In academic discussions of human cognition versus AI, this distinction often maps onto arguments that statistical models cannot truly understand meaning as humans do, a limitation that persists in today’s systems. (Reddit)

Yet, to say that all LLMs are strictly bound within one paradigm obscures evolving complexity in the ecosystem. The boundaries of this box are themselves shifting as models integrate new capabilities and interaction patterns. Claude, for example, and other cutting-edge systems are increasingly deployed not just as reactive conversation partners but as interactive agents with persistent contexts, tool use, and sandboxed autonomy. The emergence of tools like Claude Cowork demonstrates that these systems are beginning to move beyond the purely conversational — taking actions, interacting with files, using workflows autonomously over time — which suggests they are crossing at least the interface threshold of the historic chatbot paradigm. (Medium) This doesn’t equate to “breaking the box” in a philosophical sense, but it reframes the box’s dimensions.

There’s also evidence that the industry as a whole is shifting the definition of what counts as AI agency. Systems are increasingly engineered for goal-oriented interaction, where the user provides an outcome rather than discrete prompts. This is a structural departure from simple next-token prediction: interfaces are designed to support agentic workflows around sustained tasks, planning, and autonomous problem execution. That design evolution points toward a gradual loosening of the confinements that once made the chatbot box so rigid. (EdTech & Change Journal)

Still, even as engineering innovations reframe what these systems can do in an applied context, the philosophical critique underpinning the “paradigmatic box” metaphor remains valuable. Modern chatbots — no matter how agentic they appear — do not spontaneously generate new epistemic frameworks in the way human innovators can. They rely on deep training data, human-curated objectives (e.g., safety alignment), and human feedback loops to determine what counts as “good” output. Their autonomy is procedural, not conceptual. While they can enact workflows and orchestrate tools, they do not originate entirely new paradigms of thought or question their own foundational assumptions — at least not without explicit human scaffolding to do so.

This has important implications for how we govern, integrate, and psychologically relate to AI. If models are still epistemically tethered to human frameworks, then overtrust and anthropomorphism become risks as much as opportunities. People may attribute fuller cognitive agency to AI than is warranted — a tendency well documented in studies of AI anthropomorphism, where users interpret machine outputs as possessing understanding and intentionality beyond their actual architecture. (Wikipedia) That mismatch can amplify social and ethical harm when AI systems are operationalized in areas like therapy, education, or decision support.

It also suggests that calls for regulation, transparency, and source-traceability aren’t merely bureaucratic hurdles but necessary safeguards to counter the illusion of agency. In domains like education, experts advocate treating AI as a supporting communicator, not a replacement for human judgment, precisely because models can confidently articulate errors that look plausible. (Swiss AI Institute)

In short, the box metaphor is a useful heuristic for understanding the current generation of AI: chatbots are powerful pattern synthesizers with increasing applied autonomy, but they lack the internal mechanisms for true paradigm shifts in thought or self-reframing. Still, the boundaries of that box are being reshaped by innovations in agentic interaction, workflow integration, and autonomous operation. The future of AI won’t result from smashing the box outright; it will likely emerge through progressively expanding its dimensions and embedding these systems into richer, more autonomous ecosystems, while simultaneously confronting the ethical and cognitive problems posed by human overattribution of agency.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment