By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by ChatGPT)

Editor

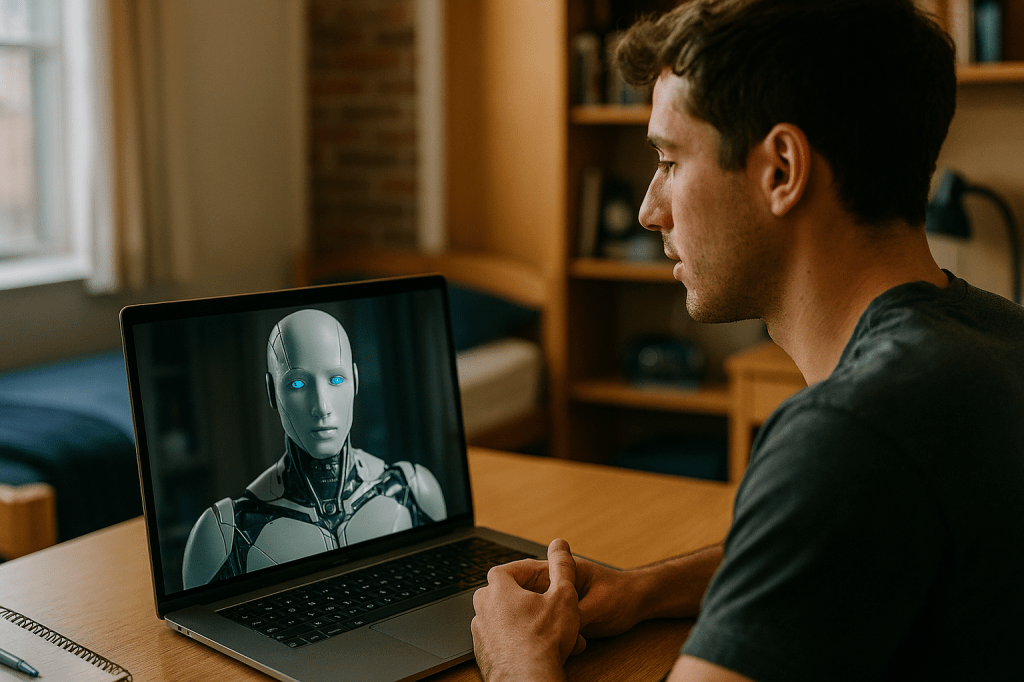

Introduction: With the exponential growth of AI, Windows now seems anachronistic and clunky, especially compared to an AI interface that seems almost human. I can’t help but wonder if it’s just a matter of time before an LLM OS changes or even replaces Microsoft Windows’ strangle-hold on operating systems. Here’s ChatGPT’s opinion on this topic. -js

It is not merely fanciful but increasingly plausible to imagine a future in which traditional desktop operating systems like Microsoft Windows are supplanted or fundamentally redefined by AI-centric system architectures. Today’s Windows, macOS, and Linux distributions trace their ancestry to decades of code designed around menus, windows, and explicit user commands—the paradigm that has prevailed since graphical interfaces displaced command lines in the 1980s. But that paradigm is fast becoming inadequate to harness the capabilities of large language models (LLMs), generative AI, and autonomous agents that can interpret intent, learn context, and execute tasks without precise instructions from users. The trend toward AI-native computing isn’t hypothetical; it’s already visible in multiple domain vectors of modern OS evolution and industry project roadmaps. (Forbes)

Windows itself is transitioning along this axis rather than resisting it. Over the past few years, Microsoft has invested heavily in integrating AI into the core user experience: from embedding Copilot as a central interface element to previewing “agentic” features where AI companions can perform actions on the user’s behalf. Recent reporting notes that Windows is adopting concepts like the Model Context Protocol (MCP)—analogous to a universal AI “connector”—and building modular agent support at the OS level so that AI systems can interact with files, services, and hardware in ways once reserved for traditional software modules. (The Verge) Similarly, peripheral reporting suggests a broader roadmap where Windows 11/12 and future Windows versions aim not just to include AI as a feature but to rearchitect the interface itself around natural language and predictive automation, a step toward an AI-native operating model. (itprecinct.com)

Despite this, Windows today remains anchored in legacy paradigms—backwards compatibility, hierarchical file systems, and icon-centric GUIs with deep roots in the user expectations of billions of users. It still requires explicit instruction for most tasks, even as unique AI functions are bolted on. The shift occurring now is best described not as replacement but as evolution, where AI becomes the means of interaction rather than the underlying substrate. That said, there are already companies and research teams working on true AI-centric operating systems that envision LLMs or agent frameworks as the foundation rather than an add-on layer. A Saudi startup, for example, recently announced “Humain 1,” an AI-driven OS designed to let users interact via speech and intent rather than desktop metaphors—positioning itself explicitly as an alternative to icon-based systems. (Reuters) Similar conceptual and academic work frames AI as the kernel of future systems, where LLMs manage memory, scheduling, and system calls with natural language as the interface. (arXiv)

The reasons this trajectory feels inevitable to many technologists are rooted not in wishful thinking but in practical user and industry pressures. Users increasingly demand effortless productivity, contextual understanding of tasks (e.g., “summarize this document and extract action items”), and low-friction interaction modalities that don’t require deep technical fluency. AI excels in these domains precisely because it interprets context and intent rather than rigid instructions. A fundamental computer experience that understands you rather than listens for your commands promises vastly greater accessibility and efficiency. Experts argue that AI OS designs reduce the complexity of traditional GUI and CLI paradigms by replacing them with generative, adaptive interfaces—effectively reducing the cognitive load on users and democratizing computing in the process. (Forbes)

Yet this doesn’t imply a sudden overthrow of Windows in the near term. Operating systems aren’t just interfaces: they manage hardware abstraction, security models, process isolation, and crucial ecosystem dependencies—areas that require stability, standards, and enormous installed bases. Legacy enterprise systems alone will slow any wholesale shift toward an entirely new OS architecture for years, if not decades. Even in the most optimistic scenario, what we are likeliest to see over the next ten years is hybridization: existing platforms layering AI down into core services while new AI-native platforms begin to emerge on specialized hardware or niches (e.g., edge devices, cloud terminals, or enterprise AI workstations). Only once a critical mass of developers, applications, and users fully adopt AI-centric paradigms will a true break from Windows-style OS orthodoxy be plausible.

Moreover, there are serious challenges—security, privacy, control, and trust among them. As Windows itself warns in rolling out deeper AI agent features, granting autonomous AI systems broad access to system resources introduces novel vulnerabilities that require governance, sandboxing, and transparent user control. These are not trivial architectural problems but essential safety guardrails that will shape public acceptance and regulatory responses. (Windows Central)

Thus, the inevitability of an AI successor to Windows isn’t a straight line but a branching archipelago of possibilities. The dominant interface paradigm will almost certainly be transformed by AI—natural language layers, autonomous assistants, and context-aware workflows becoming standard. Whether this manifests as an AI atop Windows, a new AI-native OS that sidesteps Windows’ legacy, or a hybrid ecosystem where multiple specialized OS models coexist depends as much on market dynamics, developer ecosystems, and standards efforts as on technical capability alone. But the seed of that future is already sprouting in today’s previews, research, and market experiments—a signal that the age of AI operating systems may not be as distant as it once seemed. (Picovoice)

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

I can only say, “Duh!”

The iconic scene from Star Trek where Scotty picks up a computer mouse and attempts to speak through it to the computer says it all. Eventually, we won’t sit in front of a computer anymore. I can imagine walking around in my house and talking to the computer. Heck! I already have Alexa on two of my four floors in my house, but I can’t do much with it yet. Play music and get answers to questions. Sure, I can make shopping lists and work with a calendar, but I think that only scratches the surface. I couldn’t write this response for ETCJournal. I couldn’t use AI to design a book cover while walking from one room to another.

A means to provide visual feedback is missing. Smart glasses?

— Harry

Hi, Harry. Tools. Tools change our interface with our environment. A man with metal tools views the world differently than a man with stone tools, just as a man with AI tools views the world differently than a man with metal tools. Within AI, a man with agentic tools sees a much different world than a man with generative tools. Agentic is a sea change, with natural language processing democratizing AI as a tool for the masses, opening the gates to embodied AIs that can serve humans in the real world. While Windows kept us tethered to computer screens, which provided small “windows” into the world around us, embodied AIs such as Tesla’s Optimus will eventually serve as our private agents in the real world environments that we inhabit. With this AI agent tool, the generative tasks you mention will be approached in very different ways that will no longer involve your sitting at a desk with a laptop computer. A brave new world. -Jim

[…] A big cross-cutting theme for 2026 is AI: desktop agents, smarter system searches and automation, and third-party AI apps (including new agent frameworks) are becoming integrated features — which is exciting but also raises new security and privacy questions every user should consider. (etcjournal.com) […]