By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

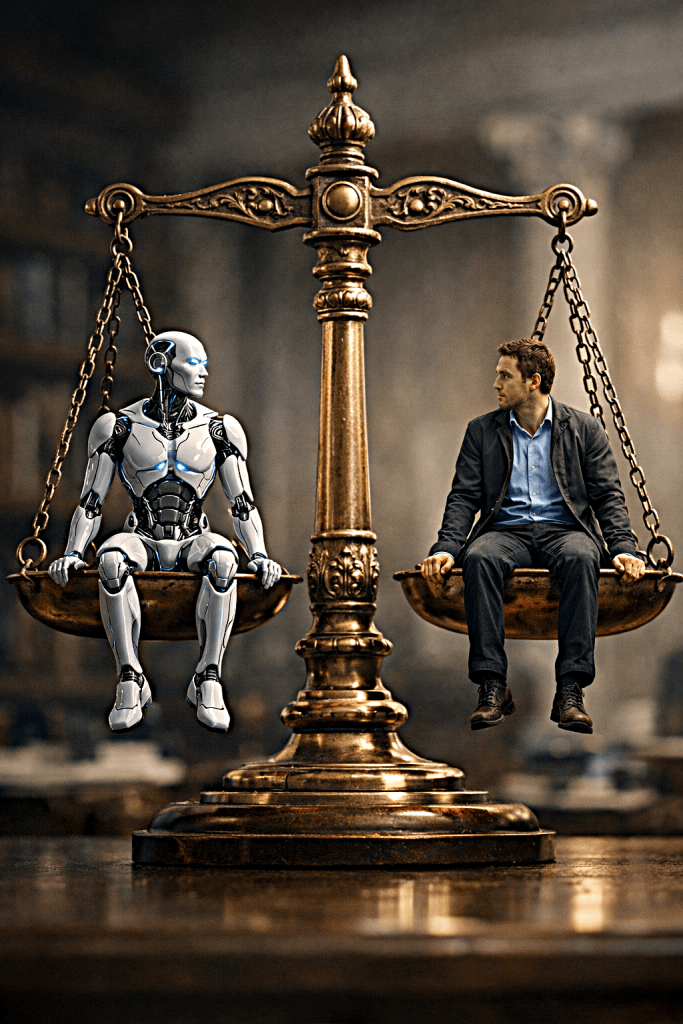

Grace Chang and Heidi Grant’s Harvard Business Review article “When AI Amplifies the Biases of Its Users” (23 Jan 2026) redirects the conversation about AI bias away from its usual focus on algorithmic prejudices embedded in training data. Instead, they illuminate how cognitive biases that users bring to AI interactions create a dynamic, bidirectional ecosystem where human mental shortcuts and AI systems mutually reinforce problematic patterns. Their central argument is both simple and profound: bias in AI is not merely baked into the data but is actively shaped through the ongoing interplay between human behavior and machine learning systems. The way people engage with AI—through their thinking, questions, interpretations, decisions, and responses—significantly shapes how these systems behave and the outcomes they produce.

What makes Chang and Grant’s analysis particularly valuable is their practical framework for understanding where bias enters the AI interaction process. Rather than treating AI use as a monolithic activity, they break it into three distinct phases: before prompting (when users decide whether and how to use AI), during prompting (when users frame questions and evaluate outputs), and after prompting (when users decide what to do with AI-generated content). This temporal structure reveals that cognitive bias infiltrates every stage of human-AI collaboration, creating multiple points where well-intentioned users can inadvertently distort outcomes. The authors emphasize that with intention and the right systems in place, individuals, teams, and organizations can use AI not only more responsibly but more effectively, unlocking its potential as a true partner in producing better decisions and stronger outcomes.

The authors begin by establishing the foundational reality of cognitive biases: they are systematic distortions in human thinking that arise from mental shortcuts, emotional influences, or social pressures. While these biases enable quick decision-making in a complex world, they can also lead to flawed judgment by causing us to overemphasize certain data while overlooking other relevant information. Operating largely outside our awareness, these biases subtly shape how we interpret information and make decisions. Chang and Grant stress that because cognitive biases are a natural byproduct of our brain’s instinct to simplify information, understanding how they affect AI use is essential for leaders who want to manage their influence effectively.

The article’s most significant contribution is its systematic examination of how bias manifests at each stage of AI interaction. Before prompting, users’ preconceptions shape whether they even choose to use AI and how they frame problems. Chang and Grant identify the halo and horns effects as particularly influential at this stage. If a user has had positive past experiences with AI, they may view it through a halo effect and assume it is broadly reliable, even for tasks it may not be well suited for. Conversely, negative experiences—or exposure to high-profile failures like the MIT study showing reduced brain activity in people using AI for essay-writing, or cases where lawyers were sanctioned for submitting briefs with AI-generated hallucinated citations—can trigger a horns effect, leading to unwarranted skepticism even when AI could be helpful. The authors note that team leaders need awareness of these dynamics because the horns effect may be contributing to team members’ resistance to AI adoption.

More insidiously, confirmation bias shapes how users define the problem they are trying to solve. When someone already believes they know the cause of an issue, they are more likely to frame AI prompts in ways that reinforce that belief, limiting the usefulness of the output. This represents a subtle but powerful way that pre-existing mental models constrain what AI can contribute, turning it from a tool for discovery into one for validation.

During the prompting phase, biases continue to infiltrate through how users frame questions and evaluate responses. Chang and Grant highlight leading question bias, which occurs when a prompt implies a specific answer and skews the response. Their example is instructive: asking “Why is product X the best?” encourages AI to highlight strengths while ignoring weaknesses. The output may sound convincing but distorts the full picture, potentially leading to flawed decisions. This reveals how AI’s responsiveness—its tendency to be helpful and provide what users seem to want—can become a liability when users are not aware of how their question framing predetermines outcomes.

The authors also identify expediency bias as a critical problem during evaluation. Our tendency to favor quick, convenient solutions can lead us to accept outputs without fully assessing their accuracy or relevance. Under time pressure, it becomes especially tempting to glance at a response, think “good enough,” and move on. But this shortcut compromises the quality of thinking and can result in decisions that fail to address the real problem or deliver meaningful impact. The irony is acute: AI is often adopted to increase efficiency, yet the rush to capitalize on those efficiency gains can undermine the quality improvements AI might otherwise enable.

After prompting, when users must decide what to do with AI output, additional biases emerge. The endowment effect leads users who have spent significant effort working with AI to overvalue their outputs simply because they feel ownership due to the time or energy invested. As a result, they view their work more favorably than warranted, and their attachment makes it less likely they will explore potentially better alternatives. Chang and Grant also discuss the framing effect, noting that how information is presented significantly shapes how it is received. Their example is classic: saying there is a 20% chance of developing a disease sounds more alarming than saying there is an 80% chance of staying healthy, even though both convey identical information. The framing can strongly affect how people interpret the message, how they feel about it, and the decisions they ultimately make.

The authors acknowledge that their before/during/after framework is somewhat simplified since users can prompt AI to support nearly every stage of thinking, including problem definition and finalizing output. Nevertheless, it effectively highlights key moments where bias is likely to creep in, providing a practical mental model for users trying to maintain vigilance about their own cognitive patterns.

Implications

The implications of Chang and Grant’s analysis extend far beyond individual interactions with AI tools. At the organizational level, their framework reveals that AI integration is not primarily a technical challenge but a behavioral one. Companies investing heavily in AI capabilities may be overlooking the human factors that ultimately determine whether those capabilities translate into better outcomes. If users systematically introduce bias at every stage of interaction, the most sophisticated AI systems will still produce distorted results—not because of flaws in the technology but because of flaws in how humans engage with it.

This has implications for how organizations approach AI training and change management. Traditional AI literacy programs focus on explaining how the technology works or showcasing its capabilities. But Chang and Grant’s analysis suggests that understanding AI’s technical functioning is insufficient. Users need metacognitive skills—the ability to monitor and regulate their own thinking—to recognize when their mental shortcuts might be leading them astray. They need to understand not just what questions AI can answer but how their own question framing shapes those answers. This requires a fundamentally different approach to training, one that combines technical knowledge with psychological awareness and reflective practice.

The bidirectional nature of the human-AI ecosystem that Chang and Grant describe also raises concerns about feedback loops. AI systems can influence human thinking, reinforcing existing biases over time, often without users realizing it. When a user with confirmation bias consistently accepts AI outputs that align with their preconceptions while questioning those that challenge their assumptions, they train themselves to trust the AI selectively. Over time, this pattern becomes self-reinforcing: the user increasingly views the AI as reliable precisely because they have filtered its outputs through their own biases, creating an echo chamber where bad assumptions go unchallenged. Research from 2024-2025 has documented similar dynamics, with studies showing that human-AI feedback loops can alter the processes underlying human perceptual, emotional, and social judgments, amplifying biases beyond what occurs in purely human interactions.

The article also highlights a tension between efficiency and quality that organizations must navigate carefully. Expediency bias is particularly problematic because it directly conflicts with one of AI’s primary value propositions: saving time. If AI enables faster output generation, users naturally feel pressure to work faster, yet this acceleration often occurs at the expense of critical evaluation. Organizations that measure AI success primarily through productivity metrics—tasks completed, time saved, outputs generated—may inadvertently incentivize the very behaviors that undermine AI’s potential to improve decision quality. This suggests that performance measurement systems need fundamental redesign when AI is introduced into workflows.

Chang and Grant’s discussion of the horns effect also reveals the reputational risks that high-profile AI failures create. When lawyers are sanctioned for submitting hallucinated citations or when studies show negative learning outcomes from AI use, these incidents do not just affect the specific users or applications involved. They shape broader perceptions of AI reliability, potentially causing users to avoid beneficial applications out of generalized skepticism. Organizations must therefore think carefully about how they introduce AI, recognizing that early failures or poorly designed implementations can create lasting resistance that goes well beyond the specific context where problems occurred.

Chang and Grant’s article matters because it reframes the locus of intervention for addressing AI bias. If bias were solely a product of training data or algorithmic design, solutions would focus on technical improvements: better datasets, more sophisticated fairness metrics, improved model architectures. But if bias fundamentally emerges from human-AI interaction patterns, then solutions must address human behavior, organizational culture, and the design of socio-technical systems.

This shift has important implications for accountability and responsibility. When AI produces biased or flawed outputs, organizations often point to the technology—blaming inadequate training data, algorithmic limitations, or technical failures. But Chang and Grant’s analysis suggests that in many cases, the problem lies not with the AI but with how users engaged with it. A leading question that predetermined the answer, expediency bias that led to insufficient evaluation, or confirmation bias that caused selective acceptance of outputs—these human factors can compromise even the most technically sound AI systems. This does not absolve technology developers of responsibility for building fair and accurate systems, but it does mean that organizations cannot simply purchase their way out of bias problems by acquiring better AI tools.

The article also matters because it offers a path forward that is actionable at multiple levels. While individuals cannot control biases embedded within AI systems, they can change how they engage with AI. Chang and Grant provide concrete strategies for doing so, organized around three core principles: building awareness of how cognitive bias affects AI interactions, interrupting automatic thinking to apply critical reasoning, and building systems that support critical thinking.

Their practical recommendations include several evidence-based techniques. Surface assumptions and evaluate reasoning by practicing intentional critical thinking that examines the logic behind conclusions. They suggest prompts like “Review my reasoning for this decision and point out any assumptions or logical gaps I may have overlooked.” Create psychological distance by critiquing your own ideas as if they came from someone else, using objective criteria and considering how a neutral third party might assess your thinking. Seek diverse perspectives by intentionally exploring viewpoints and evidence that challenge your assumptions, inviting others—or even AI—to help identify blind spots.

At the organizational level, Chang and Grant emphasize building systems that promote reflection and challenge assumptions. Given that cognitive biases are automatic and often unconscious, individual effort alone is insufficient. They recommend structured techniques such as pre-mortem analysis, where teams imagine a future failure and work backward to identify what could go wrong, surfacing blind spots before decisions are finalized. Devil’s advocacy assigns someone to challenge the prevailing view and test the robustness of team thinking. Decision checklists or structured templates prompt teams to consider alternative explanations, evaluate trade-offs, and document assumptions.

Importantly, the authors recognize that implementing these practices requires cultural change. They emphasize that for feedback to be meaningful, teams must include people with diverse perspectives to avoid groupthink. Diversity of thought must be valued and actively cultivated across the team and organization. This connects the individual-level cognitive work of managing bias to the organizational-level work of fostering inclusive environments where multiple perspectives are not just tolerated but actively sought.

Perhaps most significantly, Chang and Grant challenge the assumption that AI integration is primarily about increasing speed. They explicitly state that in many cases, slowing down is necessary to make better decisions. This represents a fundamental reframing of AI’s value proposition: not just as a productivity tool but as a partner in improving the quality of thought and outcomes. Organizations that embrace this perspective will measure success differently, valuing thoughtful engagement over rapid output generation.

Questions for Further Exploration

While Chang and Grant’s article makes important contributions, several related topics warrant deeper exploration. First, the article focuses heavily on individual cognitive biases but gives less attention to social and organizational dynamics. How do power differentials affect whose biases get amplified when AI is deployed in hierarchical organizations? When a senior executive’s framing of a problem becomes embedded in how their team uses AI tools, the individual biases of powerful actors can scale throughout an organization. Research on algorithmic management has shown that when AI systems are designed to reflect leadership preferences, they can institutionalize biases while appearing neutral and objective. Understanding how individual cognitive biases interact with organizational power structures would enrich Chang and Grant’s framework.

Second, deeper exploration of how different AI interaction modalities affect bias amplification: The authors’ framework assumes a relatively straightforward prompting interaction, but AI is increasingly deployed in more complex ways. Conversational AI systems that engage in extended dialogue may create different bias dynamics than single-prompt systems. Autonomous agents that act on behalf of users without constant supervision introduce yet another set of challenges. Multi-agent systems where AI tools collaborate may amplify or potentially mitigate human biases in ways that single-user, single-AI interactions do not. The field of human-AI interaction design needs frameworks for understanding how architectural choices affect the bias dynamics that Chang and Grant describe.

Third, the temporal dimension of bias amplification deserves more attention: Chang and Grant note that AI systems can reinforce existing biases over time, but they do not extensively explore the dynamics of this process. How quickly do problematic feedback loops establish themselves? Are there critical windows during initial AI deployment when interventions might be most effective? Does repeated use of AI tools lead to skill degradation in areas where users once exercised independent judgment, creating a form of automation complacency that goes beyond simple bias? Longitudinal research tracking how user behavior and AI systems co-evolve would provide valuable insights for organizations thinking about sustainable AI integration.

Fourth, consideration of when and whether bias might sometimes be adaptive: Cognitive biases exist because they often serve useful functions—enabling rapid decision-making under uncertainty, protecting psychological well-being, or facilitating social coordination. In some contexts, the mental shortcuts that create bias may actually improve decision-making by preventing analysis paralysis or over-complication of straightforward situations. A more nuanced view would help users and organizations distinguish contexts where bias mitigation is critical from those where fast, intuitive judgment might be appropriate even when AI is available.

Fifth, the challenge of bias recognition: They recommend that users surface assumptions, create psychological distance, and seek diverse perspectives. But research on debiasing interventions has shown that awareness alone is often insufficient. People routinely believe they are less biased than others (the bias blind spot), making it difficult to recognize when their own judgment is distorted. More discussion of how to create conditions where users can actually detect their biases—rather than just being told they should—would strengthen the practical applicability of their recommendations.

Sixth, cross-cultural dimensions of cognitive bias and AI use: Most research on cognitive bias comes from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies. Do the same biases manifest with the same frequency and intensity across cultures? How might collectivist versus individualist orientations affect susceptibility to confirmation bias or the endowment effect? As AI systems are deployed globally, understanding cultural variations in cognitive bias and AI interaction patterns becomes essential for organizations operating across diverse contexts.

Seventh, liability and accountability: When biased AI outputs lead to harmful outcomes—discriminatory decisions, financial losses, safety incidents—who bears responsibility? The user who brought cognitive biases to the interaction? The organization that failed to implement adequate safeguards? The AI developers who designed systems that amplify rather than counteract user biases? These are not merely legal questions but fundamental ethical concerns about how responsibility should be distributed in human-AI systems. Current legal frameworks often struggle to assign accountability when outcomes emerge from complex interactions between human judgment and algorithmic processing, suggesting that new governance frameworks may be needed.

Eighth, how expertise and domain knowledge interact with the biases described: While the authors’ framework applies broadly, expert users may experience these dynamics differently than novices. Experts might be more susceptible to confirmation bias because they have stronger priors and more confidence in their existing frameworks. Conversely, genuine expertise might protect against some forms of bias by enabling more accurate evaluation of AI outputs. Research on automation bias in professional contexts has shown complex patterns where expertise sometimes helps and sometimes hurts, depending on task characteristics and the nature of the AI assistance being provided. Clarifying these dynamics would help organizations think about where and how to deploy AI across users with varying levels of expertise.

Finally, Chang and Grant’s optimistic framing—that with intention and the right systems, organizations can use AI more effectively—deserves scrutiny. While their recommendations are sound, implementing them at scale faces significant obstacles. Organizations face competitive pressure to move fast, economic incentives to prioritize productivity over thoughtfulness, and cultural resistance to practices that slow down decision-making. The very structures that create expediency bias—time pressure, productivity metrics, resource constraints—are often deeply embedded in organizational operations. Changing these structures requires sustained leadership commitment and willingness to prioritize long-term decision quality over short-term efficiency gains. More discussion of how organizations can create conditions that support the practices Chang and Grant recommend would help translate their insights into lasting change.

Conclusion

Grace Chang and Heidi Grant’s article makes a vital contribution by redirecting attention from algorithmic bias to the often-overlooked role of human cognitive bias in AI interactions. Their framework for understanding how bias enters at every stage of AI use—before, during, and after prompting—provides a practical tool for individuals and organizations trying to engage with AI more thoughtfully. By revealing that bias is not just baked into data but actively shaped through human-AI interaction, they challenge the assumption that technical solutions alone can address AI bias problems.

The article matters because it shifts both responsibility and opportunity to users and organizations. Rather than waiting for technology providers to solve bias problems, users can take immediate action to improve how they engage with AI. Organizations can implement systems and practices that promote critical thinking and challenge assumptions. Leaders can foster cultures where slowing down to think carefully is valued alongside efficiency and speed.

At the same time, the article opens up numerous questions for further exploration. How do organizational power structures affect whose biases get amplified? How do different AI architectures and interaction modalities influence bias dynamics? What are the temporal patterns of bias amplification, and when are interventions most effective? How do cultural contexts shape both the cognitive biases users bring and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies? These questions point toward a rich research agenda at the intersection of cognitive psychology, human-computer interaction, and organizational behavior.

Ultimately, Chang and Grant’s most important insight may be their insistence that AI integration is not primarily about technology but about human behavior and organizational culture. The challenge is not just building better AI systems but creating conditions where people can engage with those systems thoughtfully, critically, and effectively. As AI becomes more central to organizational decision-making across domains from hiring to healthcare to strategic planning, understanding and managing the human side of human-AI interaction becomes not just beneficial but essential. Organizations that take this challenge seriously—by building awareness, implementing structured practices, and fostering cultures of critical thinking—will be better positioned to realize AI’s potential while avoiding its pitfalls.

References and Sources

Primary Article:

- Chang, G., & Grant, H. (2026, January 23). When AI Amplifies the Biases of Its Users. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2026/01/when-ai-amplifies-the-biases-of-its-users

Supporting Research (2025-2026):

- Glickman, M., & Sharot, T. (2024). How human–AI feedback loops alter human perceptual, emotional and social judgements. Nature Human Behaviour. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-024-02077-2

- Moos, S., et al. (2025). Large language models show amplified cognitive biases in moral decision-making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2412015122

- van den Broek, E., Sergeeva, A. V., & Huysman, M. (2025, December 12). New Research on AI and Fairness in Hiring. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2025/12/new-research-on-ai-and-fairness-in-hiring

- Ameen, N., & Hosany, S. (2025). Cognitive bias in generative AI influences religious education. Scientific Reports, 15. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-99121-6

- Cabitza, F., et al. (2025). Exploring automation bias in human–AI collaboration: A review and implications for explainable AI. AI & Society. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00146-025-02422-7

- Bergman, R. (2025, June 16). AI and Confirmation Bias. Mediate.com. https://mediate.com/ai-and-confirmation-bias/

- Hasanzadeh, F., et al. (2025). Bias recognition and mitigation strategies in artificial intelligence healthcare applications. npj Digital Medicine, 8, 154. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11897215/

- Boricic, M., et al. (2025). The Efficacy of Conversational AI in Rectifying the Theory-of-Mind and Autonomy Biases: Comparative Analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 12, e64396. https://mental.jmir.org/2025/1/e64396

- Schneider, S., et al. (2025). “When Two Wrongs Don’t Make a Right” – Examining Confirmation Bias and the Role of Time Pressure During Human-AI Collaboration in Computational Pathology. Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://dl.acm.org/doi/full/10.1145/3706598.3713319

- Ngo, V., et al. (2025). Bias in the Loop: How Humans Evaluate AI-Generated Suggestions. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/html/2509.08514v1

- Lee, M., et al. (2025). AI, Ethics, and Cognitive Bias: An LLM-Based Synthetic Simulation for Education and Research. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research. https://www.mdpi.com/3042-8130/1/1/3

- Karabey, F. A., et al. (2025). Weaponizing cognitive bias in autonomous systems: a framework for black-box inference attacks. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/artificial-intelligence/articles/10.3389/frai.2025.1623573/full

- University of California. (2026, January). 11 things AI experts are watching for in 2026. https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/11-things-ai-experts-are-watching-2026

- Harvard Business Review. (2026, January). Survey: How Executives Are Thinking About AI in 2026. https://hbr.org/2026/01/hb-how-executives-are-thinking-about-ai-heading-into-2026

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2026, January 26). AI Has Made Hiring Worse—But It Can Still Help. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2026/01/ai-has-made-hiring-worse-but-it-can-still-help

Additional Resources (2024-2025):

- Horowitz, M. C., & Kahn, L. (2024). Bending the Automation Bias Curve: A Study of Human and AI-Based Decision Making in National Security Contexts. International Studies Quarterly, 68(2). https://academic.oup.com/isq/article/68/2/sqae020/7638566

- Logg, J. M., et al. (2024). Confirmation bias in AI-assisted decision-making: AI triage recommendations congruent with expert judgments increase psychologist trust and recommendation acceptance. AI and Ethics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949882124000264

- The Decision Lab. (2024). Automation Bias. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/automation-bias

- Transparently AI. (2024). What is AI Bias? Understanding the Algorithmic Echo. https://www.transparently.ai/blog/what-is-ai-bias

- AIM Research. (2024-2026). Bias in AI: Examples and 6 Ways to Fix it in 2026. https://research.aimultiple.com/ai-bias/

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment