By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

(Related: Jan 2026, Dec 2025, Nov 2025, Oct 2025, Sep 2025)

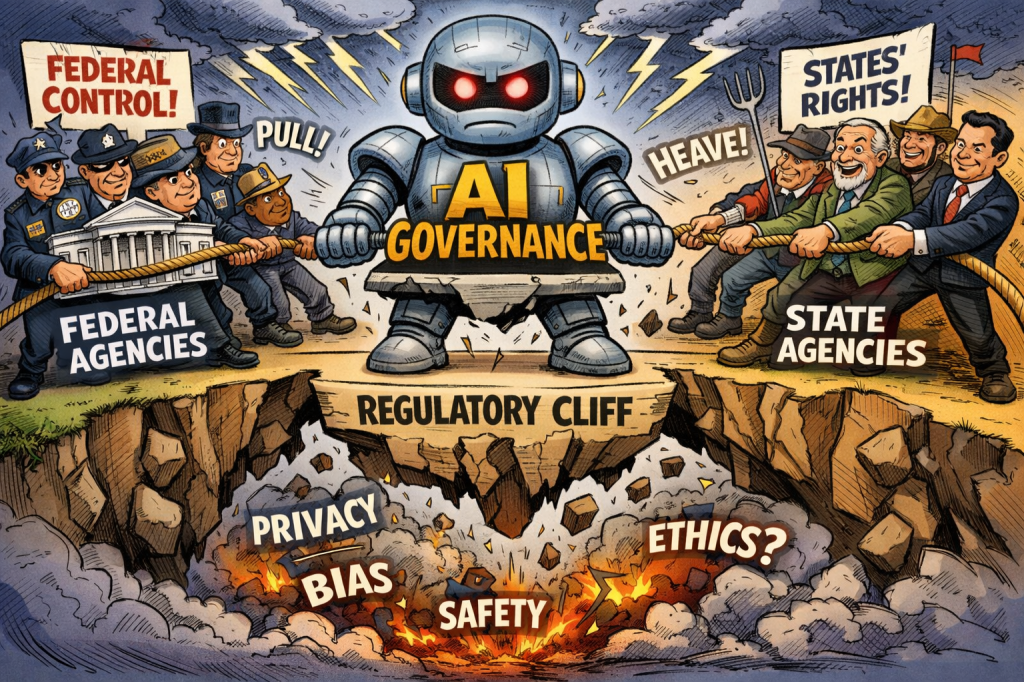

Decision 1: Will the U.S. Federal-State AI Regulatory Standoff Resolve Through Cooperation or Constitutional Clash?

February 2026 marks a critical month in the battle over who controls AI regulation in America. The question isn’t abstract anymore—it’s playing out in courtrooms, state legislatures, and federal agencies right now. Will the United States federal government and state governments find common ground on AI oversight, or will this spiral into a constitutional confrontation that fragments American AI governance for years to come?

The stakes couldn’t be higher. California, Texas, Colorado, New York, and Illinois have all enacted significant AI regulations scheduled to take effect in early 2026, covering everything from frontier model safety to employment discrimination to companion chatbots. But on December 11, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order titled “Ensuring a National Policy Framework for Artificial Intelligence” that essentially declared war on state-level AI laws. The order directs the Attorney General to establish an AI Litigation Task Force “whose sole responsibility shall be to challenge State AI laws inconsistent” with federal policy, and it orders the Commerce Department to identify “burdensome state AI laws” within ninety days—a deadline that falls in early March 2026.1

This sets up February 2026 as the month when we’ll see whether the federal government actually follows through on these threats. The California Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act took effect January 1, requiring developers of powerful AI models to implement safety protocols, conduct red-teaming, and report critical safety incidents. Texas’s Responsible Artificial Intelligence Governance Act also went live January 1, imposing disclosure and risk management obligations on AI system developers and deployers. Colorado delayed its AI Act implementation from February 1 to June 30, possibly in response to federal pressure, but the law still exists. These aren’t symbolic gestures—they’re detailed regulatory frameworks with enforcement teeth and significant penalties for noncompliance.2

The federal argument is straightforward but controversial. The executive order claims that state-by-state regulation creates an unworkable patchwork of fifty different regimes, that some state laws force AI models to embed “ideological bias” or produce false results to avoid differential outcomes for protected groups, and that states are unconstitutionally regulating interstate commerce. The order explicitly mentions Colorado’s algorithmic discrimination law as potentially forcing models to “produce false results in order to avoid a ‘differential treatment or impact’ on protected groups.” This framing positions state AI laws not just as inefficient but as threats to truthful AI and American competitiveness.3

The states aren’t backing down. California Governor Newsom has defended the state’s AI safety framework as a necessary response to federal inaction, and legal experts are already preparing arguments that the federal government lacks statutory authority to preempt state consumer protection and employment laws in the AI domain. The irony here is sharp: the Trump executive order revoked the Biden administration’s AI safety framework in January 2025, claiming it would “paralyze” the industry, and now it’s invoking federal primacy to block state efforts to fill the resulting regulatory vacuum. This isn’t just about legal theory—it’s about whether companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google can comply with one set of rules or must navigate a minefield of conflicting state requirements.4

February is when we’ll start seeing concrete moves. The Commerce Department’s ninety-day evaluation deadline is March 11, meaning February is when they’ll be actively compiling their list of state laws to target. The AI Litigation Task Force is presumably ramping up, deciding which state statutes to challenge first and on what grounds. Meanwhile, states are making their own enforcement decisions—California’s attorney general could bring the first enforcement actions under the new transparency laws, Texas could issue guidance on its governance framework, and Illinois could clarify requirements for AI in employment. Every one of these moves has the potential to trigger a federal legal challenge, and the first court battles could determine the trajectory for years.

The major actors in this decision include the U.S. Department of Justice and its new AI Litigation Task Force, the Commerce Department conducting the evaluation, state attorneys general in California, Texas, New York, Colorado, and Illinois, AI companies operating across state lines (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon), and civil liberties groups who see state laws as necessary consumer protections. Legal scholars are watching this closely because it’s not just about AI—it’s a test case for federalism in emerging technology regulation more broadly.

If February brings cooperation—say, through negotiated safe harbors where states agree to harmonize certain requirements and the federal government acknowledges state authority over consumer protection and employment—then we could get something workable. The executive order explicitly carves out state authority over “child safety protections, AI infrastructure permitting, and government procurement,” suggesting there’s at least conceptual room for a division of labor. A cooperative outcome might look like federal standards for frontier model safety (compute thresholds, red-teaming protocols, incident reporting) paired with state enforcement of algorithmic discrimination, transparency in employment decisions, and consumer protection against deceptive AI-generated content.5

But if February instead brings confrontation—with the Task Force filing preemption suits against California and Texas laws, states doubling down with aggressive enforcement, and companies caught in the crossfire—then American AI governance splinters badly. In that world, every AI lab has to maintain different versions of safety protocols, disclosure mechanisms, and even model behaviors for different jurisdictions. Innovation gets choked by compliance costs that disproportionately hurt smaller players. International observers see a fragmented American regulatory landscape and question whether the U.S. can lead on global AI governance when it can’t even get its own house in order. And the legal battles drag on for years, creating maximum uncertainty for the industry at precisely the moment when China is racing ahead on energy infrastructure for AI and the EU is implementing coherent cross-border rules.

The decision matters because February sets the tone. If the first sixty days of 2026 see the federal government and major states escalating rhetoric and filing dueling enforcement actions, trust between levels of government collapses and the possibility of negotiated compromise fades. But if cooler heads prevail—perhaps with industry groups brokering conversations, or with states and feds quietly working out modus vivendi on enforcement priorities—then there’s still a path to sensible coordination. The clock is ticking, because AI capabilities are advancing faster than any litigation timeline, and the companies building frontier systems need to know the rules of the road now, not in three years when appeals courts finally weigh in.

Decision 2: Will Global Energy Infrastructure Constraints Force a Fundamental Rethink of AI Development Trajectories?

The second critical decision facing AI in February 2026 is whether mounting evidence of insurmountable energy bottlenecks will force the industry to pivot from its current “scale at all costs” approach to something more sustainable, distributed, and efficient. This isn’t a hypothetical future problem anymore—it’s hitting right now, and February is when the financial and strategic consequences become too big to ignore.

The numbers are staggering. Global data center electricity demand is projected to nearly double from current levels of around 55 gigawatts to 84 gigawatts by 2028, with AI workloads driving most of that growth. In the United States, data centers already consume significant portions of regional electricity supply—Virginia sees 26 percent of its electricity go to data centers, and Ireland expects that figure to hit 32 percent by 2026. But the truly alarming development is the mismatch between AI ambitions and grid capacity. Elon Musk stated at Davos in January 2026 that “the limiting factor for AI deployment is fundamentally electrical power,” warning that “very soon, maybe even later this year we’ll be producing more chips than we can turn on.” Jensen Huang echoed this, noting that at the most basic layer of AI competitiveness—energy—China has roughly twice the generation capacity of the United States.6

This is creating visible, material constraints right now. Data center developers are facing years-long backlogs for critical components like natural gas turbines, and getting new generation equipment connected to the U.S. power grid can take more than a decade due to permitting, interconnection queues, and local opposition. Meanwhile, utilities are struggling to upgrade infrastructure that in many cases dates from the 1950s through 1970s—approximately 70 percent of the U.S. grid is approaching end of life. The International Energy Agency projects global data center electricity consumption could reach 945 terawatt-hours by 2030, with AI accounting for an increasingly dominant share of that demand. Training a single large language model can consume over 1,000 megawatt-hours, and inference workloads—the actual use of deployed models—are now consuming as much power as training in many cases.7

February 2026 is when companies start making hard choices based on energy reality rather than optimistic projections. Capital expenditure on AI infrastructure hit unprecedented levels in 2025—major cloud providers collectively invested hundreds of billions of dollars in new data centers. But those investments assumed reliable access to power at scale. Now, projects are being delayed or canceled because power simply isn’t available. Some companies are scrambling to secure on-site generation through contracts with nuclear plants, natural gas facilities, or even experimental small modular reactors. Others are exploring co-location deals where data centers are literally built next to power plants. And a growing number are being forced to reconsider whether the current paradigm—ever-larger training runs requiring ever-more compute—is even viable.

The strategic implications are profound. If energy becomes the binding constraint on AI development, then the entire competitive landscape shifts. Right now, success in AI is largely determined by who can afford the biggest GPU clusters and the most intensive training runs. But if power availability trumps chip availability, then the winners will be whoever can secure reliable, long-term electricity supply at scale. That could mean countries with robust energy infrastructure and low regulatory friction—which increasingly means China—pull ahead of the United States. It could also mean that architectural innovations focused on efficiency (smaller models, better algorithms, inference optimization) become more valuable than brute-force scaling.8

February is critical because it’s budget season for both companies and governments. AI labs are making decisions right now about 2026 capital allocation—how much to invest in new clusters, which regions to prioritize, whether to proceed with planned expansions. Cloud providers are deciding whether to sign long-term power purchase agreements that lock them into specific geographies and energy sources. Utilities are finalizing plans for grid upgrades and new generation capacity, often on timelines measured in years. And governments are deciding whether to fast-track permitting for energy projects, invest in grid modernization, or impose new requirements that slow everything down.

The major players in this decision include the hyperscale cloud providers (Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta), AI labs with massive training ambitions (OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, Google DeepMind), semiconductor companies (NVIDIA, AMD, TSMC), energy companies and utilities positioning to serve data center demand (Constellation Energy, Vistra Corp., NextEra Energy), governments making infrastructure policy (U.S. Department of Energy, European Commission, China’s National Development and Reform Commission), and grid operators managing increasingly volatile loads. Each of these actors has different incentives and timelines, but they’re all converging on the same recognition: business as usual won’t work.9

If February brings a fundamental rethink—with leading AI companies publicly acknowledging energy limits and pivoting toward efficiency, governments announcing coordinated infrastructure investment, and the industry adopting standards for measuring and minimizing energy consumption—then we might avoid the worst outcomes. That could look like: major labs committing to “energy budgets” for training runs and publishing efficiency metrics; increased investment in inference optimization and model distillation to reduce deployment costs; regulatory frameworks that prioritize energy-efficient architectures; public-private partnerships to fund grid upgrades in AI-intensive regions; and renewed focus on alternative approaches like neuromorphic computing and analog AI that promise radically lower power consumption.

But if February instead sees denial and doubling down—with companies continuing to announce ever-larger training clusters without credible power supply plans, governments prioritizing other infrastructure over grid modernization, and the industry treating energy as someone else’s problem—then we’re headed for a crash. That crash could take multiple forms: projects abandoned mid-construction when power doesn’t materialize, rolling blackouts in regions with concentrated data center loads, skyrocketing electricity prices that make AI training uneconomical, or regulatory backlash when residential and commercial users face service disruptions to accommodate AI demand. The public relations disaster of AI companies causing blackouts would set the field back years.10

The February decision matters because energy infrastructure moves slowly. If the industry waits until power constraints are causing widespread project failures before adapting, it will be too late to course-correct in time to maintain the current pace of AI development. But if leaders acknowledge the problem now and make strategic pivots—prioritizing efficiency, diversifying energy sources, investing in infrastructure, and being realistic about timelines—then the energy transition can happen in an orderly way that doesn’t derail AI progress. The window for that orderly transition is closing fast, and February 2026 is when we’ll see whether the industry has the wisdom to change course or the hubris to barrel ahead into predictable catastrophe.

Decision 3: Will February 2026 See Governments and Companies Confront AI’s Labor Displacement Effects or Continue Deferring the Hard Choices?

The third critical decision facing AI in February 2026 is whether stakeholders—governments, companies, workers, and the public—will finally confront the mounting evidence of AI-driven labor displacement with concrete policy responses, or whether everyone will keep kicking the can down the road while job losses accelerate. This isn’t about distant speculation anymore. Multiple converging data points suggest 2026 is the year when AI’s impact on employment shifts from theoretical to measurable, and February is when the political and economic pressure to act becomes impossible to ignore.

The numbers coming out of late 2025 and early 2026 are sobering. A November 2025 MIT study estimated that 11.7 percent of U.S. jobs could already be automated using current AI capabilities. That’s not a future projection—that’s right now, with today’s technology. Surveys of employers show they’re already eliminating entry-level positions and using AI as justification for layoffs. Companies are pointing explicitly to AI adoption when announcing workforce reductions, and venture capital investors who spend 2025 funding AI companies are now openly predicting that 2026 will be “the year of labor displacement.”11

What makes February 2026 different from earlier months of vague concern is that the displacement is becoming visible in specific sectors and job categories. Entry-level coders, call center workers, customer service roles, accounting and bookkeeping positions, technical writers, and administrative staff are seeing real cuts. These aren’t hypothetical job categories from workforce studies—these are actual people losing actual jobs. By contrast, blue-collar trades requiring physical presence and problem-solving in unstructured environments (HVAC technicians, electricians, plumbers) remain largely insulated, creating a strange inversion where white-collar workers with college degrees face more immediate automation risk than skilled tradespeople.

The investor class isn’t being subtle about what’s coming. Eric Bahn of Hustle Fund says he wants to see “what roles that have been known for more repetition get automated, or even more complicated roles with more logic become more automated,” acknowledging uncertainty about whether this leads to layoffs, higher productivity, or just augmentation of existing workers. But the directional signal is clear: investors funded AI companies to automate work, and now they expect those companies to deliver on that promise. Some VCs are even more explicit, with one stating that “2026 will be the year of agents as software expands from making humans more productive to automating work itself, delivering on the human-labor displacement value proposition.”12

February 2026 is when this becomes a political problem that demands response. In the United States, the 2026 midterm elections are just months away, and labor displacement is already emerging as a campaign issue. Senator Josh Hawley has introduced legislation requiring transparency about whether AI companies are creating or destroying jobs, framing it as a basic accountability question: “we should know: are AI companies creating jobs or destroying jobs?” Workers’ rights advocates are pushing for legislation establishing guardrails around algorithmic management, electronic monitoring, and automated hiring and firing decisions. And there’s growing pressure for policies requiring meaningful human involvement in critical decisions affecting people’s lives—healthcare, employment, credit, housing.13

The policy options on the table range from modest to transformative. On the modest end: disclosure requirements for companies using AI in hiring and firing, prohibitions on fully automated employment decisions, and funding for retraining programs. In the middle: mandates for companies to contribute to worker transition funds, tax incentives for companies that retrain rather than lay off workers, and expansion of unemployment insurance to cover AI-related displacement. On the transformative end: universal basic income experiments, reduced working hours with maintained pay, and fundamental restructuring of the social contract around work. Different countries and political factions are drawn to different parts of this spectrum, but everyone’s being forced to pick something because the status quo—doing nothing while AI eliminates millions of jobs—is becoming untenable.

The major actors in this February decision include national governments deciding whether to regulate AI’s employment effects (U.S. Congress, European Commission, individual member states), labor unions negotiating AI clauses in contracts and pushing for protective legislation, tech companies deploying agentic AI systems that automate work (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Microsoft, Salesforce), workers in exposed occupations trying to adapt and advocate for protection, and economists and policy researchers trying to understand the magnitude and pace of displacement. Each group has different information, incentives, and power, but they’re all part of the same dynamic.14

If February brings serious engagement—with governments passing initial protections for workers, companies committing to responsible AI deployment with retraining support, and labor organizations successfully negotiating terms that preserve human agency—then the transition might be managed. That doesn’t mean it will be painless, but it means there’s a framework for helping displaced workers find new roles, for ensuring AI augments rather than replaces in many contexts, and for distributing the gains from AI productivity more equitably. The optimistic case is that AI creates enough new job categories (AI trainers, oversight specialists, human-in-the-loop coordinators) and economic growth to offset the jobs it eliminates, but that only happens if there’s active intervention to ensure workers can transition.

But if February sees continued denial and delay—with companies deploying aggressive automation without retraining commitments, governments failing to pass protective legislation, and workers left to navigate displacement without support—then 2026 becomes the year of backlash. That could manifest as: political candidates winning on anti-AI platforms, workers striking or sabotaging AI systems, consumers boycotting companies perceived as job destroyers, or even violence targeting AI infrastructure. The social consequences of rapid job displacement without adequate safety nets are historically predictable and ugly. The Luddites weren’t wrong that automation threatened their livelihoods—they were just powerless to stop it. If modern workers conclude that AI is a threat to their economic survival and that no one in power cares, the blowback could be severe.15

The February decision matters because it sets the tone for how AI and labor interact over the next several years. If stakeholders use this moment to establish norms, policies, and social contracts that protect workers while enabling innovation, then AI can be a net positive for employment and prosperity. But if the dominant response is “move fast and break things” applied to people’s livelihoods, with no safety nets and no accountability, then AI becomes a political lightning rod that poisons the well for beneficial applications. The technology itself is largely neutral on these questions—it can be deployed in ways that augment workers or replace them, that concentrate gains or distribute them, that respect human agency or treat people as interchangeable cogs. February 2026 is when societies decide which version of AI’s future they’re building, and whether they’re building it deliberately or stumbling into it by accident.

Conclusion

These three decisions—federal-state regulatory coordination, energy infrastructure adaptation, and labor displacement response—aren’t happening in isolation. They’re deeply interconnected. Energy constraints will influence which AI applications get prioritized, which in turn affects labor displacement patterns. Regulatory fragmentation makes it harder to implement coherent workforce policies or energy standards. And the political dynamics around job losses will shape public tolerance for aggressive AI development that strains grids and challenges existing governance structures.

February 2026 won’t resolve any of these questions definitively, but it’s the month when trajectories get locked in. The choices made now—whether to litigate or cooperate, to pivot or double down, to protect or abandon—will determine whether AI unfolds as a broadly beneficial technology or as a source of deepening crisis across multiple dimensions. The field is at an inflection point, and the decisions facing stakeholders in February 2026 are as critical as any the industry has confronted.

Sources

1 King & Spalding, “New State AI Laws are Effective on January 1, 2026, But a New Executive Order Signals Disruption,” December 29, 2025. “The Executive Order directs the Attorney General to establish an AI Litigation Task Force (the ‘Task Force’) to challenge state AI laws deemed inconsistent with the Executive Order’s language, including on the grounds of unconstitutional regulation of interstate commerce and federal preemption.”

2 Greenberg Traurig LLP, “2026 Outlook: Artificial Intelligence,” December 22, 2025. “Colorado postponed implementation from February 1, 2026 to June 30, 2026. The Colorado AI Act establishes requirements for developers and deployers of certain ‘high-risk’ artificial intelligence systems, including obligations related to risk-management, disclosures, and mitigation of algorithmic discrimination.”

3 The White House, “Ensuring a National Policy Framework for Artificial Intelligence,” December 11, 2025. “For example, a new Colorado law banning ‘algorithmic discrimination’ may even force AI models to produce false results in order to avoid a ‘differential treatment or impact’ on protected groups.”

4 SIG, “AI legislation in the US: A 2026 overview,” January 22, 2026. “At the same time state laws begin to take effect in 2026 while the federal government signals increased willingness to contest or preempt certain state approaches.”

5 Pearl Cohen, “New Privacy, Data Protection and AI Laws in 2026,” December 31, 2025. “The order explicitly preserves state authority over child safety protections, AI infrastructure permitting, and government procurement.”

6 Energy Connects, “China Ramps Up Energy Boom Flagged by Musk as Key to AI Race,” February 4, 2026. “‘The limiting factor for AI deployment is fundamentally electrical power,’ Musk told BlackRock Inc. Chief Executive Officer Larry Fink in an interview at the World Economic Forum on Jan. 22.”

7 Data Center Knowledge, “2026 Predictions: AI Sparks Data Center Power Revolution,” January 6, 2026. “Most of the grid was built between the 1950s and 1970s, and today, approximately 70% of the grid is approaching the end of its life cycle.”

8 Yahoo Finance, “AI power and infrastructure needs boomed in 2025. At Davos, the AI story for 2026 remains the same,” January 25, 2026. “During a conversation with BlackRock (BLK) CEO Larry Fink during the summit, Nvidia (NVDA) CEO Jensen Huang said that—despite the hundreds of billions already spent by Big Tech companies—AI’s development will require ‘trillions of dollars’ of spending on what the chipmaking leader called the ‘largest infrastructure build-out in history.'”

9 Power Magazine, “How Utilities Can Prepare for the AI-Driven Energy Surge,” January 25, 2026. “After more than two decades of relative stasis, electricity demand in the U.S. is expected to increase by 25% by 2030 and by more than 75% by 2050, compared to 2023—a transformation largely driven by the surge in new data centers needed to power the artificial intelligence (AI) boom.”

10 NPR, “AI data centers use a lot of electricity. How it could affect your power bill,” January 2, 2026. “Tech companies invested hundreds of billions of dollars this past year in data centers, which use enormous amounts of electricity.”

11 TechCrunch, “Investors predict AI is coming for labor in 2026,” December 31, 2025. “A November MIT study found an estimated 11.7% of jobs could already be automated using AI. Surveys have shown employers are already eliminating entry-level jobs because of the technology.”

12 TechBuzz.ai, “Investors predict AI labor displacement accelerates in 2026,” February 5, 2026. “‘2026 will be the year of agents as software expands from making humans more productive to automating work itself, delivering on the human-labor displacement value proposition in some areas.'”

13 FOX 13 Tampa Bay, “AI’s next disruption: Analysts say 2026 could bring widespread job shifts,” December 30, 2025. “Josh Hawley (R-Missouri), who supports transparency measures, put it bluntly: ‘The basic idea is we should know: are AI companies creating jobs or destroying jobs?'”

14 UC Berkeley, “11 things AI experts are watching for in 2026,” January 15, 2026. “In 2025, unions and other worker advocates began to develop a portfolio of policies to regulate employers’ growing use of AI and other digital technologies—an area where workers currently have few rights. This year I will be watching for progress in legislation to establish guardrails around electronic monitoring and algorithmic management.”

15 World Economic Forum, “The future of jobs: 6 decision-makers on AI and talent strategies,” January 16, 2026. “By 2030, the most profound impact on workflows and strategy will arise from the collision of three forces: the commercialization of AI, a rapidly evolving talent landscape, and increasingly fragmented geoeconomics. Their interaction—not their individual effects—will determine whether organizations achieve shared productivity or face structural disruption.”

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

[…] This post draws on reporting by the ETC Journal previewing ongoing February events: AI in February 2026: Three Critical Global Decisions—Cooperation or Constitutional Clash?. It also references publicly available federal frameworks and legal concepts for […]

[…] According to reporting from ETC Journal, President Trump’s December 2025 executive order challenges state-level AI laws in California, […]

[…] to TechBuzz.ai via ETCJournal, employers are already eliminating entry-level roles and citing AI adoption. The report references […]

[…] these choices could trigger constitutional crises and social unrest. Source: ETC Journal – AI in February 2026: Three Critical Global Decisions . YouTube AI news videos cover OpenAI, agents, and hardware crunch AI‑generated YouTube news […]