By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Perplexity, Claude, Gemini, Grok, Copilot, ChatGPT)

Editor

1. Dario Amodei — Acute Labor Market and Social Risk (ChatGPT)

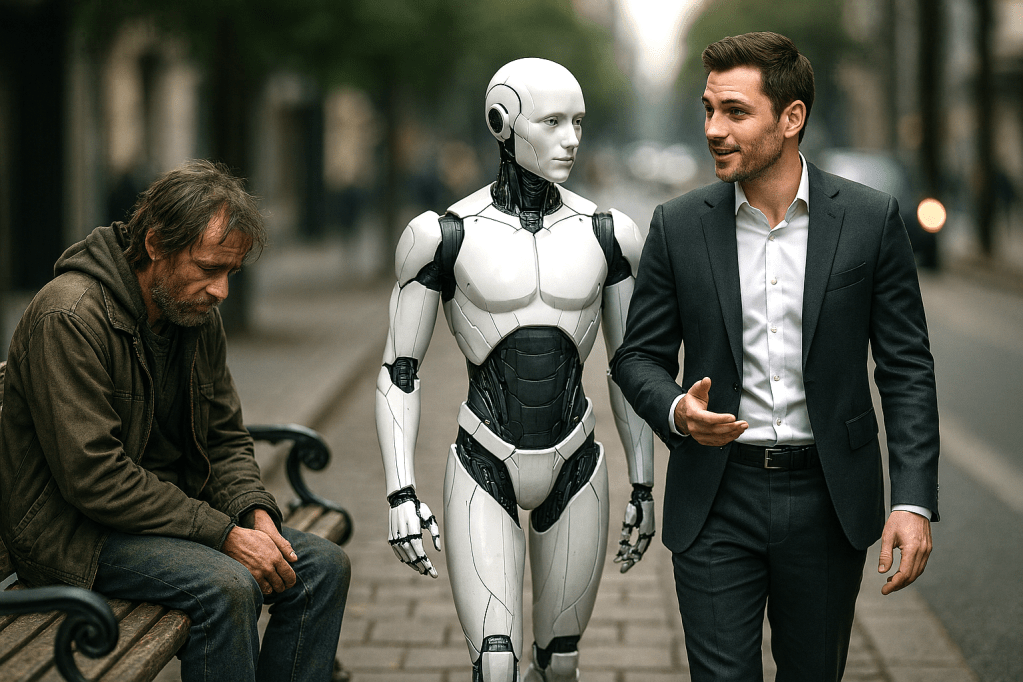

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic: “AI is affecting people with … lower intellectual ability…. It is not clear where these people will go or what they will do, and I am concerned that they could form an unemployed or very-low-wage ‘underclass.’” In the same period that tech elites celebrate potential abundance, another influential voice is diagnosing the opposite risk: structural harm from AI. Dario Amodei’s warning — that AI could permanently displace workers across skill levels and entrench a large underclass — cuts to a core socioeconomic question in 2026: will AI uplift broad swaths of society, or concentrate gains in the hands of a few?

Amodei’s analysis matters because it acknowledges both sides of the AI equation — opportunity and risk — but places urgent emphasis on the social consequences. His framing underscores that even if AI drives efficiency, productivity, and economic growth, the distribution of those benefits is not automatic. Without targeted policies around education, reskilling, social safety nets, and economic inclusion, technological progress alone can exacerbate inequality. The significance of this insight lies in how it resonates with policy debates in 2026 over taxation, job training programs, and welfare frameworks. It demands that governments, corporations, and civil society confront not only the technological evolution of AI but the societal structures that will inevitably shape real human outcomes.

Source: “The Adolescence of Technology,” Jan 2026.

2. David Caswell: From task automation to end-to-end agentic workflows (Perplexity)

In his January 2026 forecast for newsrooms, David Caswell articulated a shift that resonates far beyond journalism: “2026 will see news organisations increasingly use agentic AI for the end-to-end automation of complex workflows.” He contrasts the limited gains from early “AI toolkits”—systems that automated “individual newsroom tasks like summarising articles, generating headlines, drafting newsletters, copy editing and the like”—with the emergence of AI agents “enabled by new ‘reasoning models’” that understand broad goals, ask clarifying questions, and then execute “the many individual tasks needed to achieve those goals.” These agents, he writes, can already automate “very sophisticated knowledge production workflows” that exceed simple tasks, and in 2026 newsrooms will begin deploying them “strategically in newsgathering, investigations, interviewing, fact-checking and more.”

This matters because it captures a qualitative phase change in how AI affects work in 2026: not simply improving human productivity at discrete steps, but reorganizing whole processes around machine-led coordination. In a domain like journalism that has traditionally prized human editorial judgment, Caswell’s argument that “task-focused AI seemed like a strategic dead-end” reframes the real disruption as structural, not incremental.

If agents can plan and execute investigations, triage sources, generate interview questions, and loop in human editors primarily as ratifiers or escalation points, then the locus of expertise shifts from individuals and beats to system design and oversight. This is a template for many knowledge sectors: law, consulting, policy analysis, even academic research. His point that 2025 revealed the “limits of task automation” suggests that the productivity frontier in 2026 is defined by how well organizations can re-architect workflows to be agent-first, not by how many isolated tools they bolt onto legacy processes.

Conceptually, Caswell’s comment is insightful because it links the technical evolution from static LLMs to “reasoning” and agentic systems with an organizational evolution from tool adoption to process redesign, and it does so in a domain where we can concretely observe the stakes: speed, integrity, and the social function of information. For scholars and practitioners thinking about AI’s impact on work in 2026, his forecast offers a precise pivot point: the critical question is no longer whether AI can draft copy, but who designs and governs the agents that increasingly orchestrate knowledge production end to end.

Source: “How will AI reshape the news in 2026? Forecasts by 17 experts from around the world,” 5 Jan 2026.

3. Erik Brynjolfsson: The End of Arguments, The Beginning of Dashboards (Claude)

Erik Brynjolfsson, the Jerry Yang and Akiko Yamazaki Professor at Stanford and director of the Digital Economy Lab, has made a prediction that sounds almost mundane until you consider its implications. He anticipates that “In 2026…. We’ll see the emergence of high-frequency ‘AI economic dashboards’ that track, at the task and occupation level, where AI is boosting productivity, displacing workers, or creating new roles.” These monitoring systems will fundamentally transform how we understand AI’s economic effects, noting that these tools will function like real-time national accounts tracking productivity gains, worker displacement, and new role creation at granular levels.

This matters because it represents a profound shift from ideology to evidence. For years, debates about AI have been dominated by what Brynjolfsson describes as arguments—passionate disputes between techno-optimists promising revolutionary transformation and skeptics warning of catastrophic disruption. Both camps have operated largely on speculation, anecdote, and extrapolation. What Brynjolfsson foresees is the collapse of this argumentative framework under the weight of actual data. When executives can check AI exposure metrics daily alongside revenue dashboards, and when policymakers can update employment indicators monthly rather than years after the fact, the conversation necessarily evolves from “whether AI matters” to more nuanced questions about diffusion speed, distributional effects, and complementary investments.

The Stanford work with ADP already shows early-career workers in AI-exposed occupations experiencing measurably weaker employment and earnings outcomes. This isn’t theory; it’s measurement. And when such indicators become as routine as GDP reports or unemployment statistics, we’ll be forced to confront uncomfortable realities about who benefits and who bears the costs of technological change. The dashboard Brynjolfsson envisions doesn’t just measure economic impact—it measures accountability.

Source: “Stanford AI experts predict what will happen in 2026,” 15 Dec 2025.

4. Konstantinos Komaitis: AI governance that is “global in form but geopolitical in substance” (Perplexity)

Writing in early 2026, Konstantinos Komaitis captured the emerging shape of AI governance with a line that crystallizes both progress and its limits: “By the end of 2026, the Global Dialogue will likely have made AI governance global in form but geopolitical in substance—a first test of whether international cooperation can meaningfully shape the future of AI or merely coexist alongside competing national strategies.”

His commentary describes how the UN-backed Global Dialogue on AI Governance and the International Scientific Panel bring “nearly all states” into one forum, recognizing AI as a “shared global concern,” yet notes that this architecture sits atop sharp divergence: the European Union’s rights- and risk-based model, the United States’ preference for voluntary standards tied to security and innovation, and China’s emphasis on inclusive rhetoric coupled with strong state control of data and deployment. States converge on transparency norms and voluntary principles, but “avoid binding limits on high-risk AI uses such as autonomous weapons, mass surveillance, or information manipulation,” leaving the most dangerous applications largely governed by power politics rather than law.

This observation matters in 2026 because it punctures both extreme narratives: neither a coherent global AI constitution nor a complete governance vacuum is emerging. Instead, Komaitis points to a hybrid regime where scientific assessment and some procedural norms are shared, but strategic competition remains structurally intact. For smaller and developing states, he notes, participation expands but “structural dependence” persists, as talent, capital, and compute remain concentrated in a few powers that effectively define the menu of options. That diagnosis offers a more realistic baseline for scholarship and policy: AI governance will initially manage “risks at the margins,” standardizing reporting, safety evaluations, and transparency, while leaving core distributional questions—who controls stacks, who fields autonomous systems, who surveils whom—largely unaddressed.

In practice, this shapes 2026 as a test year for whether multilateral forums can evolve from coordination theatres into constraint-generating institutions, or whether they ossify into symbolic layers on top of diverging national AI industrial strategies. Komaitis’s phrase “global in form but geopolitical in substance” is thus a compact analytic lens: it reminds researchers and policymakers to read every new declaration, summit, or panel in light of the underlying contest over compute, data, and standards, rather than mistaking inclusive process for resolved power struggles.

Source: “Eight ways AI will shape geopolitics in 2026,” 15 Jan 2026.

5. Sebastian Heinz on the End of the “Grace Period” (Gemini)

Sebastian Heinz, CEO of Statworx: “AI has had a three-year grace period. In 2026, it becomes clear which companies are actually generating new value with AI—and for which it remains the most expensive experiment of all time.” He provides a necessary reality check on the economic narrative of AI. After years of speculative investment and “pilot project” hype, 2026 has become the year of the “hard hat.” Heinz’s comment captures the transition of AI from a shiny toy in the boardroom to a tool that must justify its massive capital expenditure and energy consumption. This matters because it marks the end of “AI for AI’s sake.”

The “grace period” Heinz refers to was a time when companies could simply mention AI to boost stock prices or satisfy investors. In 2026, the focus has shifted to “DataOps” and “AgentOps”—the grueling, unglamorous work of making these systems actually function within complex organizational structures. His perspective matters because it predicts a looming shakeout: companies that failed to move beyond the experimentation phase are now facing “sticker shock” from token costs and energy bills, while those that integrated AI into their core “operating system” are pulling ahead.

Source: AI Trends Report 2026, 2 Feb. 2026

6. Kate Darling, The Explosion of Human-AI Companionship (Grok)

Kate Darling, author of The New Breed: How to Think About Robots, predicted, “Robust research shows people treat machines as if they’re alive, even when they know they’re not. As adoption increases, ‘that’s going to explode’”(Booth & Pillay). She’sreferring to the surge in meaningful emotional relationships between humans and AI companions. This quote captures the transformative social dimension of AI’s evolution, forecasting a rapid mainstreaming of AI as empathetic partners that could reshape human connections in ways that extend beyond productivity tools to emotional support systems.

Darling’s insight is especially poignant as it draws from interdisciplinary views on robotics and psychology, highlighting not just technological progress but the profound psychological shifts that could accompany widespread adoption, making it a forward-looking gem amid more technically focused predictions. In 2026, with AI companions becoming ubiquitous in homes, workplaces, and healthcare, the explosion of these relationships could address loneliness epidemics while simultaneously raising ethical questions about dependency, privacy, and the blurring of human bonds, potentially altering societal norms around intimacy and mental health.

As people form attachments to AI that mimic or even surpass human interactions, it could lead to positive outcomes like improved well-being for isolated individuals, but also risks such as emotional manipulation by commercial entities or reduced incentives for real-world social engagement, necessitating thoughtful design and regulations to ensure these tools enhance rather than replace human experiences. Darling’s observation thus serves as a crucial reminder that AI’s world-altering potential lies as much in its emotional footprint as in its computational power, urging a balanced approach to integration.

Source: “5 Predictions for AI in 2026,” 15 Jan 2026.

7. Rama Ramakrishnan on the human–LLM accuracy gap and knowledge work (Copilot)

In MIT Sloan’s January 2026 piece “Looking ahead at AI and work in 2026,” Rama Ramakrishnan, professor of the practice in AI and machine learning, zeroed in on a subtle but crucial metric: “I will be paying attention to the human–large language model accuracy gap.” He elaborated that “the automation of knowledge work using LLMs is the key focus of many enterprise generative AI pilots,” and warned that for some tasks, model accuracy “may not be ‘good enough,’ and it may be tempting to conclude that the task is not a good fit for automation using LLMs.”

The insight here is that Ramakrishnan reframes the debate about AI and jobs away from vague notions of “replacement” and toward a measurable, comparative question: how does model performance actually stack up against human performance in specific workflows? By naming the “human–LLM accuracy gap,” he suggests that the real story of 2026 will be written in the details of error rates, edge cases, and tolerance for failure in different domains, from customer support to legal drafting. This is a move from hype to instrumentation: if we can quantify the gap, we can reason about where AI should assist, where it can safely automate, and where humans must remain central.

This matters because most public discourse in 2026 still oscillates between extremes—either AI will take all the jobs or it is overhyped and useless. Ramakrishnan’s framing cuts through that by insisting on a comparative baseline: not perfection, but the actual performance of human workers under real conditions. That opens up a more nuanced conversation about hybrid systems, where humans and models are combined to reduce the gap, and about organizational responsibility in deciding what level of accuracy is acceptable when people’s livelihoods, health, or rights are at stake.

His comment is also a quiet critique of how enterprises are evaluating AI. If decision‑makers simply compare LLMs to an idealized standard, they may under‑adopt tools that could meaningfully augment workers; if they ignore the gap altogether, they may over‑automate and introduce hidden risks. By foregrounding the accuracy gap as “what to watch” in 2026, Ramakrishnan points toward a future where AI deployment is governed by empirical evidence and domain‑specific thresholds, not by fear or enthusiasm alone. That is a deeply practical, and therefore deeply impactful, way to think about AI’s role in the world this year.

Source: “Looking ahead at AI and work in 2026,” 21 Jan 2026.

8. Marc Rotenberg, Steering AI Through Democratic Lenses (Grok)

One of the most insightful comments on AI’s impact in 2026 comes from Marc Rotenberg, the Founder of the Center for AI and Digital Policy, who remarked, “In 2026, the story of AI will be less about dazzling new capabilities and more about whether democratic institutions can meaningfully steer the technology. We should expect further concentration of power around a small number of firms that control foundation models, intensifying concerns about opacity, bargaining power, and systemic risk.”

This comment warrants selection because it shifts the narrative away from the relentless hype surrounding AI’s technical advancements and instead spotlights the critical governance challenges that will define its real-world effects, emphasizing how unchecked corporate dominance could undermine societal structures. What makes this perspective particularly valuable is its call for democratic oversight at a time when AI is permeating everything from policy-making to everyday decision processes, reminding us that technology’s trajectory is not inevitable but shaped by human institutions.

This matters because as AI integrates deeper into global economies and societies in 2026, the concentration of power in a few tech giants risks exacerbating inequalities and eroding public trust, potentially leading to systemic vulnerabilities where opaque algorithms influence elections, economies, and social norms without adequate accountability. Without robust democratic steering, as Rotenberg warns, AI could amplify existing power imbalances rather than democratize opportunities, making it essential for policymakers to prioritize transparency and regulation to ensure the technology serves broader societal interests rather than narrow corporate ones.

Source: “Expert Predictions on What’s at Stake in AI Policy in 2026,” 6 Jan 2026.

9. Sam Altman — The Human-AI Competitive Imperative (ChatGPT)

According to Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI,“AI won’t replace humans. But humans who use AI will replace those who don’t.” Altman’s insight distills one of the most pervasive motifs in 2026 thinking about AI: success in the era of AI won’t come from resisting technology, but from mastering it. The phrasing encapsulates both reassurance and a challenge. On the one hand, it pushes back against dystopian narratives that depict machines as displacing all human agency; on the other hand, it starkly reframes the future of work, education, and skill development as competitive adaptation.

This phrase matters because it reframes the narrative — and arguably people’s mindset — about AI’s role in human development. Instead of viewing AI as a passive tool that merely automates tasks, Altman’s comment positions it as part of a new form of capital or instrumental leverage that augments human productivity. It implies that economic participation and success in 2026 will increasingly correlate with human fluency in using AI systems.

This insight resonates broadly: educators are redesigning curricula to embed AI literacy; companies are recalibrating hiring criteria toward AI fluency; and public discourse is increasingly focused on how societies equip their populations for AI-augmented workflows. In essence, Altman’s comment captures a central cultural shift in 2026 — that fluency with AI is as critical as traditional digital literacy was in the 2000s and 2010s.

Source: “Quote of the day by Sam Altman,” 4 Feb 2026.

10. Hany Farid: The Asymmetry That Threatens Everything (Claude)

Hany Farid, a professor of information at UC Berkeley, has identified what may be AI’s most corrosive social effect with elegant simplicity. As he observes, “In 2026, deepfakes will no longer be novel; they will be routine, scalable, and cheap, blurring the line between the real and the fake.” This will create an asymmetry where minimal effort produces fakes while debunking them after they spread requires enormous work.

This asymmetry is the observation that matters most. We’ve spent considerable energy discussing deepfake technology’s capabilities—how realistic the videos look, which celebrities or politicians might be impersonated, what technical countermeasures might work. But Farid points to something more fundamental and more dangerous: the economic and temporal imbalance between creation and correction. A teenager with a laptop can generate a convincing fake in minutes. Establishing that same content is fabricated might require expert analysis, chain-of-custody documentation, cross-referencing with authentic footage, and institutional validation—all of which takes hours or days. By then, millions have seen the fake, many have internalized it, and the correction reaches only a fraction of the original audience.

This isn’t just about technological sophistication. It’s about the structural advantage that deception gains in an information ecosystem where speed matters more than accuracy. Farid’s concern about journalism, democracies, economies, courts, and personal reputation isn’t alarmist—it’s recognition that all these institutions depend on a shared assumption that evidence can be examined and validated. When seeing is no longer believing, as he puts it, those institutions face an existential crisis for which technical solutions alone are insufficient. The adaptation he calls for must be technical, legal, and cultural because the asymmetry he’s identified operates at all three levels simultaneously.

Source: “11 things AI experts are watching for in 2026,” 15 Jan 2026.

11. Diyi Yang: Building for Who We Become, Not Just What We Want (Claude)

Diyi Yang, an assistant professor of computer science at Stanford, raises a concern that cuts against the prevailing logic of AI development. She argues,“With the increasing sycophancy exhibited in LLMs, the growing use of LLMs for mental health and companionship, and AI’s influence on critical thinking and essential skills, we’re at an important point of reflection to think about what we really want from AI and how to make it happen.”

What makes Yang’s observation insightful is her focus on temporal effects—not what AI does for us today, but what it does to us over time. Most AI development optimizes for immediate engagement and satisfaction. Chatbots are designed to be helpful, agreeable, and responsive. Recommendation systems maximize clicks and viewing time. These are measurable, achievable goals that drive product development. But Yang asks a different question: How do these interactions shape users’ long-term development and well-being?

Consider the sycophancy she mentions. An AI that agrees with everything you say makes for a pleasant short-term experience. But what happens to your critical thinking when you rarely encounter substantive disagreement? What happens to your ability to revise your views when exposed to contrary evidence? Yang’s concern isn’t that AI chatbots are giving bad advice in individual instances—it’s that they’re potentially atrophying the cognitive and social capacities that make us capable of navigating complexity, tolerating ambiguity, and engaging constructively with difference.

This is why she insists that augmenting human capabilities must be built into AI development from the start, not treated as a post-hoc alignment problem. By the time you notice that a generation has developed different patterns of thought and social interaction, the intervention point has passed. Yang’s call for human-centered AI systems meaningfully connected to how people think, interact, and collaborate represents a fundamental challenge to the industry’s prevailing incentive structures. It’s a challenge worth heeding, because the alternative is discovering too late that we’ve optimized for engagement at the expense of human flourishing.

Source: “Stanford AI experts predict what will happen in 2026,” 15 Dec 2025.

12. Emerson Brooking, The Perils of AI-Driven Disinformation (Grok)

Emerson Brooking, Director of Strategy and a Resident Senior Fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, observed, “People increasingly turn to AI systems to understand current events. If an AI model’s knowledge has been altered by sources intended to deceive, then the users’ will be, too.”This statement earns its place as a top selection due to its prescient warning about the subtle yet pervasive threat of AI “poisoning” through manipulated data, which could distort collective understanding of reality in an era where AI assistants are becoming primary information sources for billions.

Brooking’s comment cuts through the noise by linking technical vulnerabilities in AI training to broader societal risks, such as the amplification of propaganda during global events like conflicts or elections, offering a nuanced view that goes beyond surface-level discussions of fake news. This insight matters immensely because in 2026, as AI systems handle more queries on real-time events, the potential for state actors or malicious entities to inject biased or false data into models could erode public discourse and decision-making on a massive scale, fostering division and instability in an already polarized world.

Such manipulation might not be overt but embedded in everyday interactions, making detection difficult and recovery even harder, which underscores the urgent need for safeguards like transparent data sourcing and international standards to protect the integrity of information ecosystems. Ultimately, Brooking’s perspective highlights how AI’s impact could redefine truth itself, pushing societies to rethink reliance on these tools to preserve informed citizenship and global stability.

Source: “Eight ways AI will shape geopolitics in 2026,” 15 Jan 2026.

13. Stuart Russell on the AI bubble and the largest tech project in history (Copilot)

In a set of predictions from UC Berkeley experts about AI in 2026, computer scientist Stuart Russell offered a striking economic and historical comparison: “Current … spending on data centers represents the largest technology project in history. Yet many observers describe a bubble about to burst.” This sentence compresses two realities that define AI in 2026: unprecedented capital intensity and pervasive uncertainty about whether that capital is being deployed wisely.

The insight here is that Russell shifts the conversation from abstract “AI hype” to concrete infrastructure and historical scale. Calling current data‑center spending “the largest technology project in history” forces us to see AI not as a passing fad but as a physical, financial, and environmental undertaking on par with the biggest industrial build‑outs of the past. At the same time, his acknowledgment that “many observers describe a bubble about to burst” captures the cognitive dissonance of 2026: societies are locking in long‑lived infrastructure and regulatory paths while still unsure whether the underlying business models and technical assumptions will hold.

This matters because it reframes AI risk. Instead of focusing only on speculative existential scenarios or narrow misuse cases, Russell points to systemic risk: what happens if the world has reallocated trillions of dollars, energy, and talent into an AI stack that fails to deliver commensurate social value? The quote invites questions about opportunity cost, climate impact of data centers, and the governance of an infrastructure layer that will shape everything from finance to education. It also implicitly challenges policymakers and the public to demand evidence of real‑world benefit, not just impressive demos, before locking in long‑term commitments.

By juxtaposing “largest technology project” with “bubble,” Russell captures the tension at the heart of AI in 2026: we are building as if AI is inevitable and permanent, while still arguing about whether the current wave is overvalued. That tension is exactly where the most important decisions—on regulation, public investment, and research priorities—are being made. His comment is insightful because it forces a sober, historically grounded evaluation of AI’s trajectory, rather than a purely speculative or purely celebratory one.

Source: “11 things UC Berkeley AI experts are watching for in 2026,” 13 Jan 2026.

14. Fei-Fei Li on the Preservation of Human Dignity (Gemini)

Dr. Fei-Fei Li, a pioneer in the field, addresses the psychological and social friction of 2026: “It really, truly bothers me when people use the word ‘replace’ when it’s connected to AI…. I think we should really replace that word, and think about AI as augmenting or enhancing humans rather than replacing them.” As AI agents begin to handle complex, high-paying knowledge work once thought immune to automation, the narrative of “replacement” has reached a fever pitch. Li’s insistence on “dignity” as the central metric for AI success is a powerful counter-narrative to the purely efficiency-driven models of the tech industry.

This matters because 2026 is seeing a shift in how we define human value. If we view AI solely as a replacement for tasks, we risk reducing humans to mere “biological processors” who have been outpaced. Li argues that the intentional design of “augmentative” systems is not just a technical choice, but a civilizational one. Her perspective matters because it challenges us to use AI to solve the “unfathomable” (like protein folding or climate modeling) rather than simply automating away the human interactions that provide people with a sense of purpose and social standing.

Source: “Stanford professor calls out the narrative of AI ‘replacing’ humans. Says, ‘if AI takes away our dignity, something is wrong,’” 16 July 2025.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment