By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

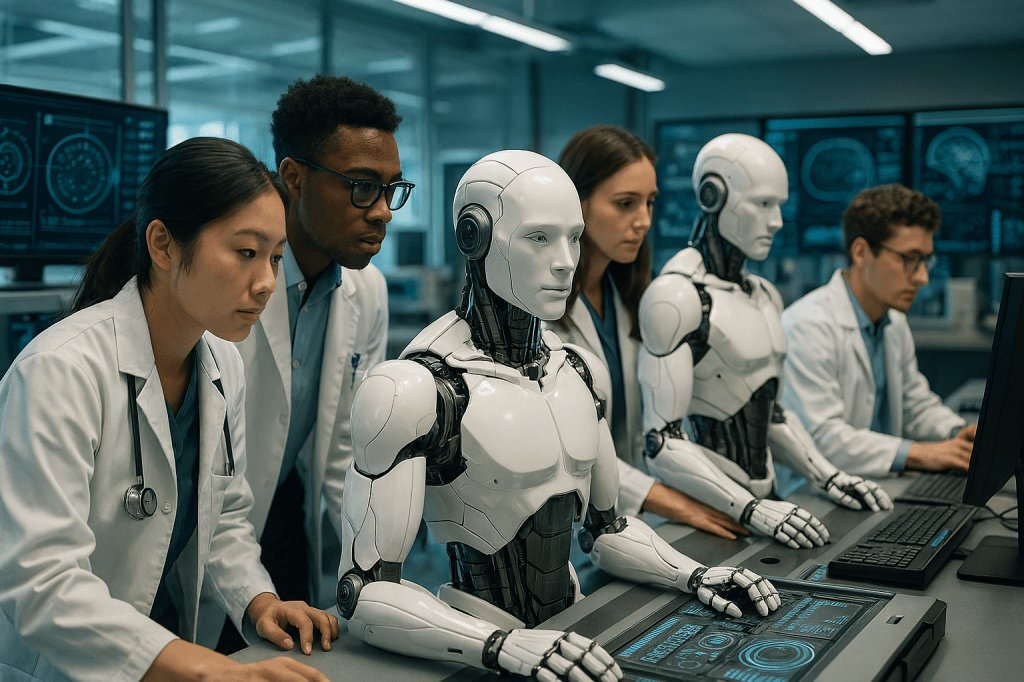

Introduction: The integration of artificial intelligence into medical practice represents one of the most transformative shifts in healthcare history. As AI-powered diagnostic tools, predictive analytics, and clinical decision support systems become increasingly prevalent, medical schools face an urgent imperative to prepare future physicians not merely to coexist with these technologies, but to master them as essential tools of their trade. Three institutions—Stanford University School of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai—have emerged as pioneers in this educational transformation, each developing distinctive approaches to ensure their graduates can thrive in an AI-augmented healthcare ecosystem. This review examines their innovative curricula, future projections, and the broader implications of their efforts for medical education and patient care.

1. Stanford University School of Medicine: Building an Adaptable Framework for a Moving Target

Source: D’Ardenne, K. (2025, September 22). Paging Dr. Algorithm. Stanford Medicine Magazine.

Projections for the AI Future (5-10 Years)

Stanford Medicine’s vision for the AI-augmented future of medicine is both ambitious and pragmatic, rooted in the recognition that the technology itself will evolve faster than any fixed curriculum could accommodate. Jonathan Chen, the institution’s AI faculty champion and an assistant professor with over two decades studying intelligent systems in medicine, frames the challenge starkly: the 2022 release of ChatGPT represented a watershed moment comparable to the invention of the internet itself, fundamentally upending everything about medical training and evaluation.

Stanford’s leadership projects that within the next five to ten years, AI will transform clinical practice across multiple dimensions. First, they anticipate AI becoming ubiquitous in diagnostic workflows, with algorithms routinely assisting physicians in interpreting imaging studies, laboratory results, and patient histories. The technology is expected to handle increasingly complex pattern recognition tasks that currently consume substantial physician time and cognitive energy. Second, AI is projected to dramatically reduce administrative burdens through automated documentation, with tools like Microsoft’s DAX Copilot already recording patient encounters and drafting clinical notes. This shift promises to return precious time to physicians for direct patient care and the uniquely human aspects of medicine that machines cannot replicate.

Perhaps most significantly, Stanford envisions AI fundamentally altering the temporal dynamics of medical education. As Aditya Narayan, a student in the MD/MBA program, explains, AI-powered simulation tools will enable students to practice clinical reasoning much earlier in their training. Rather than waiting for clinical clerkships in their third year to apply theoretical knowledge to real patients, students will engage with AI-generated patient scenarios that provide instant feedback and unlimited practice opportunities. This compression of the learning timeline could produce physicians who arrive at their residencies already possessing clinical reasoning skills that traditionally required years to develop.

The institution’s leaders also recognize AI’s darker potentials. Biases embedded in training data could perpetuate or amplify health disparities. Overreliance on algorithmic recommendations might erode physicians’ clinical judgment and diagnostic acumen. Privacy violations and the erosion of the doctor-patient relationship represent additional concerns. Stanford’s five-to-ten-year outlook therefore includes not just technological advancement but the parallel development of robust ethical frameworks, regulatory guardrails, and professional norms to ensure AI enhances rather than diminishes medical practice.

Innovative Curriculum Design

Beginning in fall 2025, Stanford Medicine implemented what may be the nation’s most comprehensive integration of AI across the entire medical curriculum for both MD and physician assistant students. The program represents a philosophical departure from treating AI as an elective or supplementary topic; instead, it positions AI literacy as foundational to modern medical practice, analogous to anatomy or pharmacology.

The curriculum rests on four core learning objectives that serve as organizing principles. First, students must understand how different types of AI systems work—not at the level of computer scientists, but with sufficient technical literacy to evaluate their strengths, limitations, and failure modes. This includes grasping fundamental concepts like machine learning, neural networks, and large language models. Second, students learn practical applications of AI tools in clinical settings, including when to use them, how to interpret their outputs, and how to integrate AI recommendations with clinical judgment. Third, the curriculum addresses ethical and legal dimensions, including patient privacy, algorithmic bias, liability questions, and the evolving regulatory landscape. Fourth, students develop critical evaluation skills, learning to assess AI outputs using the same statistical rigor applied to diagnostic tests and clinical trials.

What makes Stanford’s approach particularly innovative is its recognition that AI in healthcare represents “a moving target,” as Chen emphasizes. Rather than creating a fixed curriculum that would rapidly become outdated, Stanford has built an adaptable framework that can incorporate new technologies and applications as they emerge. The curriculum intentionally builds on existing knowledge foundations. For instance, students already learn about sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify those with a disease) and specificity (the ability to correctly identify those without a disease) when evaluating diagnostic tests. Stanford teaches students to apply these same concepts when evaluating AI algorithms, which can produce false positives and false negatives just like any diagnostic tool.

The program features several cutting-edge technological implementations developed at Stanford. Clinical Mind AI, created under the direction of Thomas Caruso and Shima Salehi, exemplifies the institution’s innovation. This platform allows students to conduct simulated patient interviews through voice conversation with AI-powered virtual patients. Unlike traditional standardized patient encounters, which require expensive actor training and faculty supervision, Clinical Mind AI provides unlimited practice opportunities with immediate feedback. The system is deliberately designed with a modular “Lego set” architecture that allows new AI capabilities to be swapped in as the technology advances, without requiring wholesale system redesign.

Another Stanford innovation is AI Clinical Coach, developed by Sharon Chen and integrated directly into the electronic health record system. This tool listens as students present patient cases to instructors, then generates summaries and creates reports identifying whether students reached correct diagnoses and utilized all relevant information. By automating aspects of assessment and feedback, the system frees faculty to focus on higher-order teaching while ensuring students receive consistent, detailed performance evaluation.

The curriculum also includes practical workshops on prompt engineering—learning how to effectively communicate with generative AI systems to obtain useful responses. Clinical informatics fellows Dong Yao and Shivam Vedak created a freely available workshop that demystifies how generative AI works using language accessible to those without computer science backgrounds. This emphasis on practical skills reflects Stanford’s understanding that future physicians must be not just passive consumers of AI tools but active, sophisticated users capable of leveraging these technologies to maximum effect.

Why These Efforts Matter

Stanford’s AI integration matters for several interconnected reasons that extend far beyond curriculum innovation. Most fundamentally, it addresses a widening gap between medical education and medical practice. As Chen observed, when ChatGPT launched, half of practicing physicians didn’t even know what a chatbot was. Yet AI is already embedded in clinical workflows at leading medical centers. This disconnect creates serious risks: physicians unprepared to use AI effectively may misinterpret its outputs, over-rely on flawed recommendations, or fail to leverage powerful capabilities that could improve patient care. By ensuring all students graduate with AI literacy, Stanford prevents future physicians from arriving at their first day of residency already technologically obsolete.

The curricular approach also responds to legitimate concerns about AI’s potential to erode core clinical skills. Some critics worry that if students rely too heavily on AI during training, they may never develop the pattern recognition abilities, clinical reasoning skills, and diagnostic intuition that define medical expertise. Stanford’s response is nuanced: the institution views AI not as a replacement for traditional learning but as a tool that can accelerate skill development. Just as medical students master multiplication tables before using calculators, Stanford ensures students understand underlying clinical logic before leveraging AI shortcuts. The Clinical Mind AI platform, for instance, doesn’t eliminate the need to learn patient interviewing—instead, it provides more opportunities to practice those skills earlier and more frequently than traditional methods allow.

Stanford’s framework model addresses another critical challenge: the breathtaking pace of AI advancement. A curriculum designed around today’s AI capabilities would be obsolete within months, not years. By creating an adaptable structure that can incorporate new technologies as they emerge, Stanford ensures its educational investment remains relevant. This approach also models for students a crucial professional skill—the capacity to continuously learn and adapt as their field evolves. In an era of rapid technological change, the ability to evaluate and integrate new tools may be more valuable than mastery of any particular technology.

The institution’s emphasis on critical evaluation carries particular importance. Early enthusiasm for AI has sometimes given way to concerning reports of algorithmic bias, where systems perform poorly for underrepresented populations, or “hallucinations,” where AI confidently presents fabricated information as fact. Stanford’s insistence that students learn to evaluate AI outputs using rigorous statistical methods—assessing not just whether an AI recommendation sounds plausible but whether it meets evidence-based standards for sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility—builds a generation of physicians who will be appropriately skeptical consumers of AI, demanding validation and transparency rather than accepting technological solutions uncritically.

Finally, Stanford’s work matters because it shapes the broader conversation about AI in medicine. When a leading institution implements comprehensive AI education, it sends powerful signals to other medical schools, residency programs, and healthcare systems. The freely available workshops, published curriculum frameworks, and licensing of tools like Clinical Mind AI to institutions worldwide extend Stanford’s influence far beyond its own students. In this sense, Stanford functions not just as an educator of physicians but as an innovator advancing the entire field’s approach to technological integration.

The ultimate measure of Stanford’s success will emerge over the coming decade as its graduates enter practice. Will they prove more adept at leveraging AI to improve patient outcomes? More skilled at identifying and correcting algorithmic biases? Better able to maintain the human connection at the heart of medicine even as technology handles routine tasks? Will they drive innovation in clinical AI applications, asking better questions and identifying unmet needs that developers can address? These outcomes remain to be seen, but Stanford has positioned itself—and by extension, its students—to help answer them.

2. Harvard Medical School: Cultivating AI Innovators Through Specialized Training

Source: Boyle, P. (2025, May 15). Medical schools move from worrying about AI to teaching it. AAMC News.

Projections for the AI Future (5-10 Years)

Harvard Medical School approaches the AI future with a dual focus: preparing all medical students to be effective users of AI tools in clinical practice, while simultaneously training an elite subset to become the innovators who will create the next generation of medical AI systems. This bifurcated strategy reflects Harvard’s assessment that the field needs both broad-based AI literacy among physicians and deep technical expertise among those who will drive the technology forward.

Harvard’s leadership projects that over the next five to ten years, AI will transition from a specialized tool used primarily by early adopters to a standard component of every physician’s toolkit. Bernard Chang, dean for medical education at Harvard, emphasizes that AI will automate routine clinical tasks, allowing medical schools to refocus their curricula on the irreducible human elements of medicine—empathy, ethical reasoning, complex decision-making, and the therapeutic relationship itself. This vision anticipates a profound shift in how medical education allocates limited instructional time. Rather than teaching students to perform tasks that machines can handle more efficiently, Harvard can dedicate more resources to cultivating the uniquely human capacities that define excellent doctoring.

The school’s AI in Medicine PhD track, however, reveals a more ambitious projection: that the boundaries between medicine and computer science will increasingly blur, creating a new category of physician-scientists who seamlessly combine clinical insight with technical prowess. As Arjun Manrai, assistant professor of biomedical informatics, explains, the program seeks “computationally enabled students who are deeply interested in medicine and health care.” These individuals will not merely use AI tools developed by others; they will identify clinical needs, design novel algorithms, validate their performance, and translate them into practice. Harvard projects that over the coming decade, such physician-scientists will drive breakthrough advances in early disease detection, precision medicine, drug discovery, and clinical decision support.

Harvard also anticipates significant challenges accompanying these opportunities. The school recognizes that as AI capabilities expand, regulatory frameworks, liability standards, and ethical guidelines must evolve in parallel. Questions about who bears responsibility when an AI system makes an error, how to ensure algorithmic fairness across diverse patient populations, and how to maintain patient privacy while leveraging large datasets for AI training remain incompletely resolved. Harvard’s integration of AI ethics into core courses reflects the conviction that future physicians must grapple with these dilemmas throughout their training, not as afterthoughts but as central considerations shaping how AI is developed and deployed.

Innovative Curriculum Design

Harvard’s curricular innovation operates on two distinct but complementary tracks. For the general medical student population, AI is being woven into existing courses rather than taught in isolation. This integration strategy reflects the philosophy that AI should be understood not as a separate domain but as a set of tools applicable across all areas of medicine. In the Computationally Enabled Medicine course, for instance, students use AI alongside other computational methods to analyze complex biomedical data, including genomic information and epidemiological patterns. This approach ensures students see AI in context, understanding how it complements and enhances traditional analytical approaches rather than replacing them.

Harvard’s integration extends to clinical training through its Health Sciences and Technology track, where incoming students receive a one-month intensive introduction to AI in healthcare. This early exposure establishes foundational knowledge that subsequent courses can build upon. The school has also developed an AI “tutor bot” designed to provide personalized learning support, answering student questions and adapting explanations to individual learning needs. This represents a meta-application of AI—using the technology not just as an object of study but as an active participant in the educational process itself.

The AI in Medicine PhD track represents Harvard’s most ambitious curricular innovation. This rigorous program combines elite medical training with deep expertise in computer science, machine learning, and data science. Students work directly with leading AI researchers to develop novel tools incorporating generative language models, diverse data types, and computer vision with the explicit goal of improving clinical decision-making and biomedical research. The program demands exceptional mathematical, scientific, and medical aptitude. Admission is highly selective, targeting students who can operate at the intersection of multiple demanding disciplines.

The curriculum emphasizes hands-on research from the outset. Rather than spending years on coursework before engaging with real problems, students immediately begin working on cutting-edge challenges at the boundary of AI and medicine. Recent projects have included developing AI systems to analyze medical imaging, creating tools to predict patient deterioration in intensive care units, and building algorithms to personalize cancer treatment recommendations based on genetic profiles. This research-intensive approach accelerates students’ transition from learners to contributors, positioning them to make meaningful scientific advances even during their training.

Harvard has also implemented AI education in its flipped classroom model, where students learn content independently before class, then use class time for application and practice. AI tools analyze student responses to pre-class quizzes, identifying common misconceptions and knowledge gaps. Faculty can then tailor in-class instruction to address these specific needs rather than delivering generic lectures. As Chang explains, “AI can take all of these however many hundreds of responses each day” and provide faculty with granular feedback on student understanding. This application demonstrates how AI can enhance pedagogical effectiveness even beyond its clinical applications.

The school’s approach to ethics education deserves particular attention. Rather than treating ethics as a standalone topic covered in a single course, Harvard integrates ethical considerations throughout the curriculum. When students learn about AI applications in imaging, they simultaneously consider questions of algorithmic bias and whether systems trained predominantly on data from certain demographic groups will perform adequately for others. When studying clinical decision support, they examine liability questions and the risk that physicians might uncritically defer to algorithmic recommendations. This integrated approach ensures students develop the habit of evaluating both the technical performance and the ethical implications of AI systems as inseparable dimensions of the same analysis.

Why These Efforts Matter

Harvard’s dual-track approach to AI education matters because it addresses different but equally important needs. The integration of AI literacy across the general curriculum ensures that all Harvard-trained physicians will enter practice with baseline competence in evaluating and using AI tools. This broad-based education creates a large cohort of clinicians who can effectively leverage AI to improve patient care, identify when algorithms are producing questionable results, and advocate for their patients when technological solutions prove inadequate. At a time when AI is rapidly penetrating every specialty, from radiology to dermatology to psychiatry, this widespread literacy becomes a public health imperative.

The AI in Medicine PhD track addresses a different but equally critical need: the shortage of individuals who can actually create the next generation of medical AI systems. While computer scientists can build sophisticated algorithms, they often lack the clinical insight to identify the most pressing problems or to design solutions that integrate seamlessly into clinical workflows. Conversely, physicians who understand clinical needs may lack the technical skills to translate those insights into working systems. The physician-scientists graduating from Harvard’s PhD track bridge this divide, combining deep medical knowledge with cutting-edge technical expertise. These individuals will shape the future of medical AI not by using tools others create but by building fundamentally new capabilities.

Harvard’s emphasis on ethics throughout the curriculum matters because AI presents novel ethical challenges that traditional medical ethics frameworks may inadequately address. Consider algorithmic bias: if an AI system performs less accurately for racial minorities because its training data underrepresented those populations, is that a technical problem requiring better data, an ethical problem demanding immediate disclosure to affected patients, or both? If an AI system recommends a treatment that seems suboptimal to an experienced physician, who bears liability if that recommendation is followed and harms the patient—the physician, the algorithm developer, the hospital that deployed the system? Harvard’s approach ensures students develop the conceptual tools to navigate these dilemmas before they arise in practice, when the stakes involve actual patient welfare.

The school’s integration strategy also addresses a practical challenge facing medical education: curricular overcrowding. Medical students already struggle to master an enormous volume of material across anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, pathology, and countless other domains. Adding AI as yet another standalone requirement would exacerbate this burden and likely relegate it to lower priority compared to more traditional topics. By weaving AI throughout existing courses, Harvard ensures students encounter the technology repeatedly in relevant contexts without requiring them to carve out additional time from already packed schedules.

Harvard’s work also sends important signals to other medical schools and to the broader medical community. When one of the world’s premier medical institutions commits to comprehensive AI education, it validates the importance of this competency and provides a model that other schools can adapt. The AI in Medicine PhD track, in particular, establishes a precedent for deep integration of computer science into medical training, potentially inspiring similar programs elsewhere. As these physician-scientists graduate and take positions at research institutions, pharmaceutical companies, medical technology firms, and academic medical centers, they will drive AI innovation across the entire healthcare ecosystem, multiplying Harvard’s impact far beyond its own walls.

The success of Harvard’s approach will ultimately be measured in the contributions its graduates make to medical knowledge and patient care. Will the general population of Harvard-trained physicians prove more effective at using AI to improve diagnoses and treatment plans? Will they be better able to maintain appropriate skepticism toward algorithmic recommendations while still leveraging AI’s genuine capabilities? Will graduates of the PhD track create breakthrough diagnostic tools, discover novel therapeutic targets through AI-assisted drug discovery, or develop systems that extend access to expert-level care to underserved populations? These questions will take years to answer definitively, but Harvard has established the educational infrastructure to make such outcomes more likely.

3. Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai: Leading Through Accessible Innovation

Source: Mount Sinai Health System. (2025, May 5). Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai expands AI innovation with OpenAI’s ChatGPT Edu rollout.

Projections for the AI Future (5-10 Years)

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai has staked its vision of the AI future on a bold proposition: that every physician, regardless of specialty or practice setting, will need to understand how to effectively use generative AI tools in their daily work. This projection goes beyond anticipating that AI will be available to physicians who seek it out; Mount Sinai’s leadership believes AI will become as ubiquitous and essential to medical practice as email or electronic health records. The school’s May 2025 announcement of providing all medical and graduate students with access to ChatGPT Edu positions the institution at the vanguard of this transition.

David Thomas, Dean for Medical Education at Mount Sinai, frames the school’s five-to-ten-year outlook explicitly: “With robust safeguards in place—including full HIPAA compliance and integrated protections to support safe and appropriate use—our deployment of ChatGPT Edu gives our students the opportunity to engage critically with generative AI. It’s about helping them build the judgment, skills, and ethical grounding they’ll need to lead in a future where AI will increasingly intersect with medicine.” This vision encompasses several key projections.

First, Mount Sinai anticipates that AI will become deeply integrated into medical learning itself, functioning as what Thomas describes as “a dynamic learning aid, similar to a digital study partner.” Students will use AI to strengthen clinical reasoning by working through complex cases, to understand intricate pathophysiological mechanisms through interactive questioning, and to receive immediate feedback on their thinking. This represents a fundamental shift in medical education’s temporal dynamics: rather than waiting hours or days for faculty feedback, students will engage in real-time dialogue with AI systems that can identify gaps in their reasoning and suggest areas for deeper exploration.

Second, the school projects AI becoming central to medical research, particularly for students pursuing combined MD/PhD degrees or research-intensive career paths. AI is expected to assist with data analysis, help with programming for computational research projects, identify patterns in large datasets, and even help brainstorm novel research directions. As the school’s announcement notes, current students are already using ChatGPT Edu for “data analysis and coding assistance,” suggesting these applications will only deepen as the technology matures and students become more sophisticated users.

Third, Mount Sinai envisions AI transforming how medical students develop their professional communication skills. Students like Faris Gulamali, profiled in CBS News coverage of the ChatGPT Edu rollout, use the platform to practice explaining complex diagnoses to simulated patients in accessible language, to prepare for surgical procedures by querying the system about anatomy and potential complications, and to refine their bedside manner through iterative practice. This anticipates a future where communication with AI systems becomes a routine part of professional development, with students continuously honing their ability to convey medical information clearly and compassionately.

Importantly, Mount Sinai’s vision includes explicit recognition of AI’s limitations and risks. Dennis Charney, the school’s dean, emphasizes that “students aren’t using AI to make medical decisions, but to sharpen their thinking, challenge their assumptions, and become more confident, critical thinkers.” This framing acknowledges that over the next five to ten years, as AI capabilities expand, the temptation to defer to algorithmic recommendations will grow. Mount Sinai’s educational philosophy anticipates this risk and positions AI as a tool to support human judgment rather than replace it, with the ultimate clinical decision-making authority remaining firmly with the physician.

Innovative Curriculum Design

Mount Sinai’s curricular innovation centers on unprecedented access to cutting-edge generative AI technology. By becoming the first medical school in the nation to provide all students with ChatGPT Edu, Mount Sinai has effectively made advanced AI a universal resource rather than a specialized tool available only to those with technical expertise or personal subscriptions. This democratization of access represents a fundamental philosophical shift: AI competency is not viewed as an optional enhancement for interested students but as a core requirement for all future physicians.

The technical infrastructure supporting this access deserves particular attention. Through a formal agreement with OpenAI, Mount Sinai has secured guarantees around data privacy and security that address the healthcare sector’s stringent requirements. The ChatGPT Edu platform is fully HIPAA-compliant, meaning students can engage with clinical scenarios and patient data (appropriately de-identified) without risking privacy violations. Crucially, the agreement ensures that no data, prompts, or responses submitted through Mount Sinai’s institutional accounts will be used to train OpenAI’s models. This protection addresses a critical concern in medical education: that student learning activities might inadvertently contribute data to commercial AI systems without appropriate consent or oversight.

The platform provides students with capabilities beyond what free ChatGPT users can access. Students can make more complex queries, engage with STEM-focused content at greater depth, and utilize enhanced features for analyzing scientific literature and medical data. They also have the ability to create customized GPTs—specialized versions of the AI trained for specific tasks like creating biochemistry flashcards or practicing physical examination techniques. These custom GPTs can be shared among Mount Sinai students, creating a collaborative learning ecosystem where students build and refine educational tools for each other’s benefit.

Mount Sinai’s curricular approach emphasizes training students to use AI as a complement to, rather than substitute for, traditional learning methods. The school explicitly positions ChatGPT Edu as a “digital study partner” that students can consult at any time but that does not replace human instruction, clinical supervision, or evidence-based practices. This framing helps students develop appropriate mental models for AI’s role—seeing it as a resource to enhance their learning rather than a crutch that might undermine skill development.

The curriculum includes structured training on responsible AI use, delivered through workshops and coursework that address ethical considerations, technical limitations, and best practices for effective prompting. Students learn about the phenomenon of AI “hallucinations,” where the system generates plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information. They practice techniques for verifying AI outputs against authoritative sources. They explore questions of algorithmic bias and fairness, considering how AI systems trained primarily on data from certain populations might perform less reliably for others.

Faculty members are simultaneously exploring how ChatGPT Edu can transform their own teaching practices. Some are using the platform to streamline curriculum development, generate case studies for classroom discussion, and create assessment questions. Others are investigating how AI can support their scholarly work, from drafting grant proposals to analyzing research data. This parallel faculty engagement serves multiple purposes: it helps educators develop firsthand understanding of AI’s capabilities and limitations, it models continuous learning and technological adaptation for students, and it creates opportunities for faculty to discover novel pedagogical applications that can be shared across the institution.

The school’s AI Steering Committee on Teaching, Learning, and Discoveries provides ongoing governance and strategic direction. This multidisciplinary body, which includes clinical faculty, researchers, educational leaders, legal counsel, and cybersecurity experts, ensures that AI integration aligns with the school’s educational mission while addressing regulatory, ethical, and technical challenges as they emerge. The committee’s existence reflects Mount Sinai’s recognition that effective AI integration requires sustained institutional commitment rather than one-time implementation.

Why These Efforts Matter

Mount Sinai’s ChatGPT Edu initiative matters first and foremost because it addresses a fundamental equity issue in medical education. Prior to this program, students with financial resources could subscribe to advanced AI tools independently, gaining advantages in learning efficiency and research productivity over peers who could not afford such subscriptions. Students with technical backgrounds or computer science training could more easily leverage AI capabilities compared to those approaching the technology for the first time. By providing universal access to a sophisticated AI platform, Mount Sinai levels the playing field, ensuring all students have equal opportunity to develop AI literacy and leverage these tools for their education.

The program’s emphasis on HIPAA compliance and data privacy sets a crucial precedent for the field. As other medical schools consider similar initiatives, Mount Sinai’s agreement with OpenAI demonstrates that it is possible to provide students with powerful generative AI tools while maintaining the strict confidentiality protections that healthcare demands. This proof of concept may accelerate AI adoption across medical education by showing that privacy concerns, while legitimate, can be addressed through appropriate technical and legal safeguards.

Mount Sinai’s approach also matters because it recognizes that AI literacy cannot be taught effectively through lecture alone—it requires hands-on practice. By giving students daily access to ChatGPT Edu, the school ensures they develop intuitive understanding of the technology’s capabilities and limitations through repeated use. Students learn through experience when AI provides valuable insights versus when it generates flawed outputs. They develop skill at crafting effective prompts through iterative experimentation. This experiential learning complements more formal instruction about AI principles and creates a student body that will enter residency already comfortable using these tools in clinical contexts.

The initiative addresses a timing challenge facing medical education: AI capabilities are advancing so rapidly that curriculum development cannot keep pace. By the time a traditional course on AI applications in medicine is designed, approved, piloted, and fully implemented, the specific tools and techniques it teaches may be obsolete. Mount Sinai’s approach—providing students with access to cutting-edge AI tools as they become available—ensures students are learning with the most current technology. The platform will receive updates and improvements from OpenAI as they are released, meaning students automatically gain access to enhanced capabilities without waiting for curriculum revisions.

The cultural impact of Mount Sinai’s initiative extends beyond its direct educational benefits. By making AI integration so prominent—with national media coverage of the school’s partnership with OpenAI—Mount Sinai sends a powerful message to prospective students, faculty, patients, and the broader medical community. The school positions itself as an institution embracing technological innovation while maintaining rigorous commitment to patient safety and educational excellence. This reputation may help Mount Sinai attract students who are excited about the intersection of medicine and technology, faculty who want to explore AI applications in their specialties, and research collaborators interested in investigating how AI can improve medical education.

The program also creates valuable data on how medical students actually use AI in their learning. Mount Sinai has the opportunity to study usage patterns, identify which applications prove most educationally valuable, understand where students struggle, and discover unanticipated creative uses. Paul Lawrence, dean for scholarly and research technologies, noted that the institution will be “focusing on evaluating the student experience and how the tool supports curricular success.” These insights can inform not only Mount Sinai’s own curricular refinement but also provide evidence to guide AI integration efforts at other institutions.

Finally, Mount Sinai’s emphasis on critical thinking and appropriate skepticism matters profoundly. In providing students with powerful AI tools, the school simultaneously teaches them that these tools have significant limitations. Students learn that AI can generate plausible but incorrect information, that it lacks true understanding of the concepts it discusses, and that it cannot replace clinical judgment informed by direct patient interaction and comprehensive knowledge. By instilling this critical perspective early, Mount Sinai helps ensure its graduates will be thoughtful consumers of AI who demand validation and transparency rather than accepting technological solutions uncritically. In an era when AI hype often outpaces actual capabilities, this commitment to critical evaluation represents an essential safeguard for patient safety and quality of care.

Conclusion

Stanford, Harvard, and Mount Sinai have each developed distinctive approaches to preparing physicians for an AI-augmented future, but several common themes emerge from their efforts. All three institutions recognize that AI literacy must become a core competency for all physicians, not an optional specialization for the technically inclined. All three integrate AI education throughout their curricula rather than treating it as a standalone topic. All three emphasize critical evaluation of AI outputs, teaching students to assess algorithmic recommendations with the same rigor they apply to any diagnostic or therapeutic tool. And all three maintain unwavering commitment to human judgment remaining central to clinical decision-making, positioning AI as a powerful adjunct but never a replacement for physician expertise and the therapeutic relationship.

These institutions’ efforts matter because they shape not only their own students but the entire field of medical education. The curricula, tools, and approaches they develop will be studied, adapted, and implemented by medical schools worldwide. The physicians they train will become leaders in academic medicine, healthcare delivery, and medical technology, carrying forward the perspective that AI is not something to fear or resist but a set of capabilities to master and deploy thoughtfully. Their work establishes that integrating AI into medical education is not just possible but essential—and that doing so need not come at the expense of the humanistic values that define excellent medical care.

The next decade will reveal whether these educational investments produce the anticipated outcomes: physicians who leverage AI to deliver better care, who maintain appropriate skepticism while embracing genuine innovations, who identify and correct algorithmic biases, and who preserve the human connection at medicine’s core even as technology handles routine tasks. But by acting now, while AI’s integration into healthcare remains nascent, these institutions help ensure that future physicians shape AI’s role in medicine rather than being shaped by technologies developed without their input. In this sense, their curricular innovations represent not just educational reform but an assertion of professional agency in an era of profound technological change.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment