By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Copilot)

Editor

(Related:“The Decline of U.S. Public Education Began in 1967”)

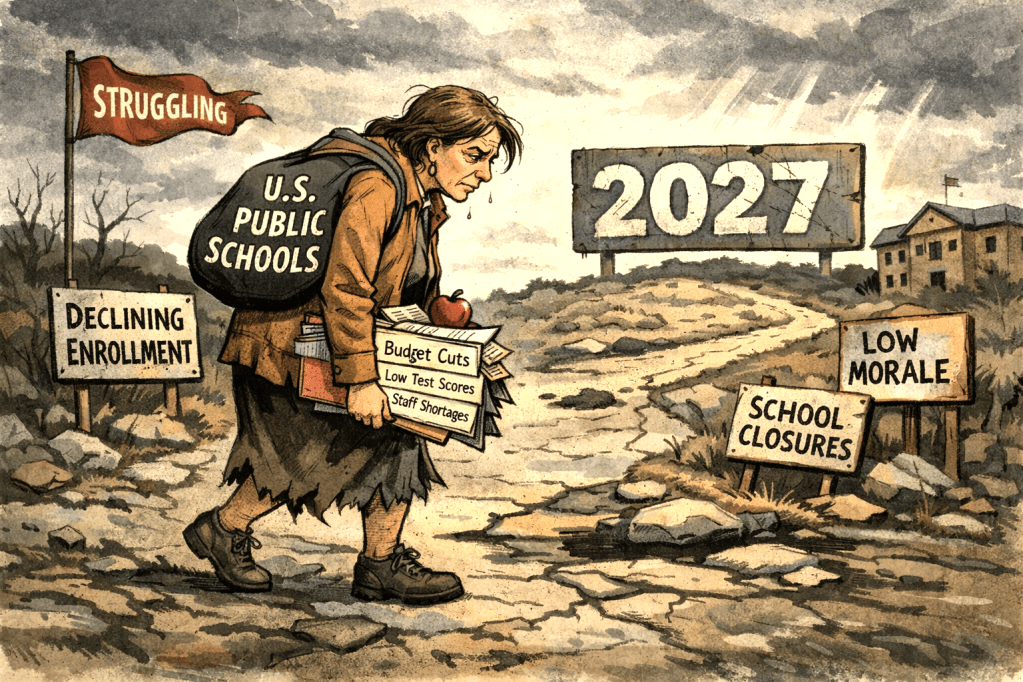

By early 2026, U.S. public education is not in free fall, but it has not fully recovered from the shocks of the pandemic and the political turbulence of the past decade. The best description is “fragile and uneven”: some districts—often better resourced and more affluent—are stabilizing or even improving, while many high‑poverty systems remain stuck with serious workforce, attendance, and achievement problems. The 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) shows that, nationally, students have still not returned to pre‑pandemic performance in any tested grade or subject, and that “as a nation, U.S. students have not recovered from the devastating impact the pandemic had on education,” with widening gaps between higher‑ and lower‑performing students.(nagb.gov)

At the same time, survey work from RAND’s American Educator, Youth, and Parents Panels paints a picture of schools grappling with chronic absenteeism, student mental health, and political pressures, even as many educators report incremental progress and strong commitment to their students. RAND’s 2025 “State of Public Education in Five Charts” highlights persistent chronic absenteeism, rising concerns about student behavior and mental health, and ongoing staffing challenges as defining features of the current landscape.(rand.org)

In important ways the system is still in decline relative to pre‑2019 benchmarks, especially for the most vulnerable students. But the decline is no longer a sudden plunge; it is a slow, uneven drag, with pockets of recovery and innovation coexisting alongside deep structural problems.

Five telling symptoms of the current decline

The first symptom is persistent, historically high chronic absenteeism. Analyses of district‑level data into 2024 show that chronic absenteeism—students missing at least 10 percent of school days—remains “a serious problem,” with national rates in 2023–24 about 57 percent higher than before the pandemic and only modest improvement from the previous year.(aei.org) RAND’s 2025 report on absenteeism finds that in roughly half of urban districts, more than 30 percent of students are chronically absent in 2024–25, and that a quarter of surveyed youth do not think being chronically absent is a problem—an attitudinal shift that makes recovery harder.(rand.org)

The second symptom is incomplete academic recovery and widening achievement gaps. The 2024 NAEP results show that national scores remain below 2019 levels in all tested grades and subjects, and that “higher‑performing students drove most of the progress made in 2024,” meaning lower‑performing students are being left further behind.(nagb.gov) A 2025 analysis from The Hunt Institute describes the 2024 NAEP data as a “complex picture” in which some states and subgroups show gains, but overall recovery is uneven and achievement gaps have persisted or widened.(hunt-institute.org) The Education Recovery Scorecard, using state and district data, reports that no state had fully recovered in both math and reading by 2025 and that higher‑income districts were nearly four times more likely than the lowest‑income districts to have recovered in both subjects.(educationrecoveryscorecard.org)

The third symptom is a severe and persistent teacher shortage, especially in high‑need schools and subjects. A 2025 fact sheet from the Learning Policy Institute estimates that, as of mid‑2025, 48 states and D.C. employed about 366,000 teachers who were not fully certified for their assignments and that tens of thousands of positions remained vacant, a clear sign that shortages are both widespread and structural rather than temporary.(learningpolicyinstitute.org) Other 2025 analyses estimate that more than 400,000 K–12 positions are either vacant or filled by under‑qualified educators, roughly one in eight teaching jobs nationwide, with burnout, low pay, and poor working conditions cited as key drivers.(freedomineducation.org)

The fourth symptom is the intensification of culture‑war conflicts, especially around curriculum and books. PEN America’s 2025 report “The Normalization of Book Banning” describes book censorship in public schools as “rampant and common,” documenting 6,870 cases of school book bans in the 2024–25 school year and noting that never before have so many books been systematically removed from school libraries.(pen.org) Coverage by ABC News in 2025 similarly warns of a “disturbing” normalization of book bans, with campaigns increasingly targeting materials related to race, racism, and LGBTQ+ topics.(abcnews.go.com)

The fifth symptom is rising concern about student mental health, behavior, and school climate. RAND’s 2025 “State of Public Education” commentary highlights that educators report elevated levels of student anxiety, depression, and disruptive behavior, which they see as major barriers to learning and staff retention.(rand.org) Other national surveys and reports from 2024–25, including those tied to NAEP and federal data collections, connect historic achievement declines with increased chronic absenteeism and student well‑being challenges, underscoring that academic and mental health crises are intertwined rather than separate problems.(nagb.gov)

Underlying causes

The causes of these five symptoms are layered and mutually reinforcing. Chronic absenteeism is driven by a mix of health, economic, and cultural factors. AEI’s 2025 report notes that absenteeism spiked during the pandemic and has remained elevated, with disadvantaged districts experiencing higher rates and larger increases.(aei.org) RAND’s 2025 absenteeism study finds that students most often cite sickness, but also report disengagement, family responsibilities, and safety concerns; importantly, a sizable share of youth no longer view chronic absence as a serious issue, suggesting a shift in norms about school attendance.(rand.org)

Academic stagnation and widening gaps are closely tied to both absenteeism and unequal recovery investments. The Education Recovery Scorecard shows that federal relief funds did mitigate learning loss, especially in higher‑poverty districts, but that how districts spent the money mattered greatly; districts that invested heavily in tutoring, extended learning time, and evidence‑based interventions saw better gains than those that spread funds thinly.(educationrecoveryscorecard.org) NAEP‑based analyses emphasize that lower‑performing students—who are more likely to be in high‑poverty schools and to experience chronic absenteeism—have not benefited equally from recovery efforts, leading to persistent or widening gaps.(hunt-institute.org)

Teacher shortages stem from long‑standing structural issues that the pandemic intensified. The Learning Policy Institute’s 2025 fact sheet points to low relative pay, high stress, inadequate preparation and mentoring, and limited professional autonomy as key drivers of attrition and recruitment challenges, especially in special education, STEM, and high‑poverty schools.(learningpolicyinstitute.org) Other 2025 analyses emphasize burnout from larger class sizes, increased student needs, and politicized scrutiny, as well as the rising cost of living in many regions, which makes teaching less financially viable.(freedomineducation.org)

The surge in book bans and curriculum conflicts is rooted in broader political polarization and organized campaigns targeting public institutions. PEN America’s 2025 report argues that new state laws and regulations have made it easier to challenge and remove books, and that some politicians have used threats to funding and public pressure to push ideological agendas in schools.(pen.org) Advocacy groups tracking censorship note that these efforts disproportionately target books by or about people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals, raising equity and inclusion concerns and contributing to a climate of fear among educators and librarians.(freedomtolearn.net)

Finally, student mental health and behavior challenges reflect both post‑pandemic trauma and broader social stressors. RAND’s educator surveys show that teachers and principals see student anxiety, depression, and disruptive behavior as among their top challenges, often linked to family economic hardship, social media pressures, and community instability.(rand.org) Federal and NAEP‑related analyses connect these well‑being issues to attendance and achievement, suggesting that academic recovery cannot be separated from investments in counseling, social‑emotional learning, and school climate.(nagb.gov)

Trajectory for 2026 and 2027

Looking ahead through 2026 and 2027, the trajectory is best described as cautiously pessimistic at the national level, with real but limited reasons for local optimism. On the positive side, there is growing recognition among policymakers and researchers that chronic absenteeism, teacher shortages, and student mental health are structural problems requiring sustained, systemic responses rather than short‑term fixes. The continued work of organizations like RAND, the Education Recovery Scorecard, and state education agencies suggests that data‑driven strategies—high‑dosage tutoring, targeted funding, and expanded student support services—are being refined and, in some places, scaled.(educationrecoveryscorecard.org, rand.org)

However, several headwinds make a rapid turnaround unlikely. First, federal pandemic relief funds (ESSER) are expiring, which will force districts to either cut or find new revenue for many of the very interventions that have supported recovery. Second, teacher labor markets do not change quickly; given current vacancy and under‑certification levels, even optimistic projections suggest that shortages will persist into 2026–27, especially in high‑need schools and subjects.(learningpolicyinstitute.org) Third, political polarization around curriculum, book bans, and school governance shows no sign of abating in the near term, and may intensify in an election‑heavy period, diverting attention and energy away from instructional improvement and student support.(pen.org)

For student outcomes, the most plausible scenario is slow, uneven improvement rather than a clean “recovery.” NAEP and related analyses suggest that higher‑performing and better‑resourced districts are already on a modest upward trajectory, while lower‑performing, higher‑poverty districts risk being left behind without targeted, sustained investment.(nagb.gov, hunt-institute.org) Chronic absenteeism is likely to remain elevated above pre‑pandemic levels through at least 2026–27 unless districts and communities can shift norms around attendance and address underlying health, safety, and engagement issues.(aei.org)

In short, by 2026 the U.S. public school system is still carrying the weight of the past several years: unfinished academic recovery, entrenched inequities, workforce instability, and politicized conflict. The next two years will likely deepen the divide between systems that manage to stabilize and innovate and those that continue to struggle. Whether the overall story bends toward renewal or further erosion will depend less on isolated programs and more on whether states and communities choose sustained, equitable investment over short‑term, polarized battles about what schools are allowed to teach and who they are for.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment