By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

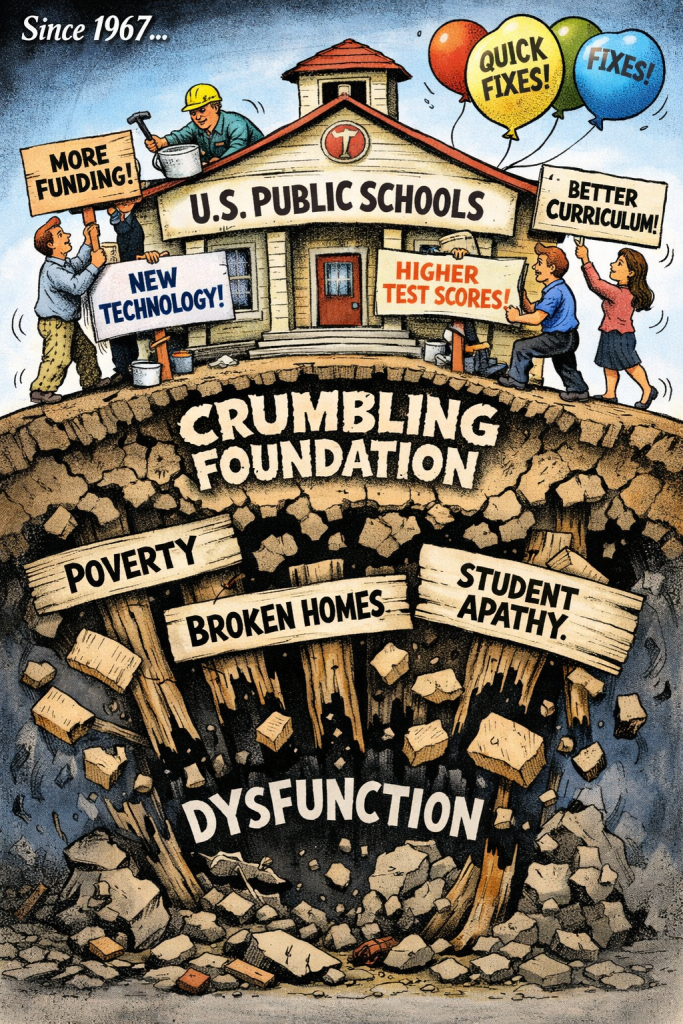

Introduction: The “Status of U.S. Public Schools in 2026: ‘slow, uneven decline’” (ETC, 13 Feb 2026) paints a troubling picture of contemporary American education. While many observers point to COVID-19 or recent political developments as primary causes, the evidence suggests that these factors merely accelerated long-standing structural problems. This report examines the deeper historical trends that have shaped the current crisis, tracing patterns that extend back decades before the pandemic and exploring whether the traditional K-12 education model itself is sliding into obsolescence.

The 1967 Achievement Peak: A Turning Point

The story of American public education’s decline does not begin in 2020 or 2016. According to research cited in Econlib’s comprehensive analysis, the trajectory changed dramatically in 1967. After rising consistently for fifty years, student achievement scores on various standardized tests dropped sharply that year and continued declining through 1980. This represented a devastating loss of educational ground. Students graduating in 1980 had learned approximately 1.25 grade-level equivalents less than their 1967 counterparts, a decline so severe that by the turn of the century, conservative estimates placed the economic growth lost due to diminished academic achievement at 3.6 percent of the 2000 gross national product.(Econlib)

What makes this decline particularly puzzling is that it contradicted prevailing theories about school performance. The achievement drop affected students across demographic groups, with more able students declining at least as much as less able ones. Measures of inferential ability and problem-solving declined more sharply than simpler computational tasks. The decline hit suburban schools harder than inner-city ones and affected both private and public institutions. Most tellingly, achievement fell even as average class sizes shrank from twenty-seven students in 1955 to fifteen in 1995, and despite steadily increasing per-pupil expenditures. Traditional explanations blaming poverty, family instability, large class sizes, or insufficient funding could not account for these patterns.(Econlib)

The 1970s: Ideological Shifts and Funding Constraints

The 1970s witnessed a fundamental ideological shift in American education that would have lasting consequences. During this decade, the conventional wisdom held that “schools don’t make a difference.” Studies debunking the ambitious reform programs of the 1960s led many to conclude that if schools didn’t matter, then curriculum content and academic rigor didn’t matter either. This determinist view of schooling justified what education historian Diane Ravitch documented as a steady decline in academic rigor, with textbooks filled with banal literature, boring writing, and inaccurate content.(edweek)

SAT scores declined throughout the 1970s and 1980s, though researchers noted that this partly reflected the democratization of higher education as more students from disadvantaged backgrounds took the exam. However, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, introduced in 1969, showed more concerning trends. While NAEP scores would eventually show slow upward movement, the literacy scores for white students peaked in 1975, and math scores peaked in the early 1990s. For the nation’s seventeen-year-olds specifically, there have been no gains in literacy since NAEP began in 1971, and performance on mathematics showed no progress since 1990.(Brookings, cft)

The late 1970s also brought a financial constraint that would permanently reshape American education. The “taxpayers’ revolt” led to the passage of Proposition 13 in California and similar measures in other states. These propositions froze property taxes, a major source of public school funding. The consequences were dramatic. California, which ranked first in the nation in per-student spending in 1978, had dropped to forty-third by 1998. This twenty-year fiscal decline established a pattern of resource constraints that would persist for decades.(raceforward)

The 1983 Wake-Up Call That Didn’t Wake Anyone Up

The publication of “A Nation at Risk” in 1983 represented a watershed moment in American education discourse. The National Commission on Excellence in Education used apocalyptic language, warning of “a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.” The report claimed that if an unfriendly foreign power had imposed America’s schools on the country, it might have been considered an act of war.

However, education researcher Gerald Bracey later demonstrated that the report engaged in highly selective use of data. The commission chose specific metrics that painted the darkest possible picture while ignoring contradictory evidence. For instance, the report highlighted steady declines in science achievement scores for seventeen-year-olds from 1969 to 1977, but ignored that science scores for nine- and thirteen-year-olds did not support the crisis narrative. The report contributed to a perception of educational failure that may have been more severe than reality warranted.(americanheritage, fordhaminstitute)

Despite the alarm bells, fundamental structural problems persisted. The 1980s saw increased attention to educational quality and the emergence of “effective schools” research showing that school policies could significantly affect student achievement. Governors of both parties came together to enact standards and testing reforms. Yet forty years later, the problems raised in “A Nation at Risk” remain largely unresolved. Before COVID-19, thirty-four percent of fourth graders scored below the basic level on NAEP, meaning they weren’t reading at grade level. The pandemic then erased two decades of achievement gains, with eighth-grade math students scoring below basic increasing from thirty-one percent in 2019 to thirty-eight percent in 2022.(fordhaminstitute)

The Structural Problems: Governance, Incentives, and Institutional Capture

As tax-supported schools grew larger from the mid-twentieth century onward, control shifted fundamentally from parents to teachers and administrators. The focus of school governance gradually moved from academic achievement to staff pay and working conditions. Beginning in 1955, some states allowed teachers’ organizations to deduct dues from paychecks, bar nonunion members from teaching, and bargain collectively. The percentage of American school districts with at least half of teachers covered by collective bargaining rose from one percent in 1960 to thirty-six percent in 1992.

Research suggests that unionization increases school budgets, with increases primarily directed toward higher teacher salaries and reduced class sizes to lower workload rather than toward academic outcomes. School officials, seeking to avoid offending politically powerful groups, presided over the steady decline in academic rigor that Diane Ravitch documented.(econlib)

This shift in institutional priorities helps explain a puzzle that has vexed policymakers for decades: why increased spending and smaller class sizes failed to improve or even maintain educational outcomes. The system had been captured by interests that, while not necessarily opposed to student learning, prioritized other objectives when allocative decisions were made.

Pre-Pandemic Enrollment Decline: The Slow Exodus Begins

Long before COVID-19, demographic and market forces were already reshaping American public education. Public school enrollment growth stagnated between 2012 and 2019, edging up only two percent to hold near fifty million students. During this same period, the U.S. total fertility rate had slipped to 1.71 births per woman, well below replacement level, foreshadowing a smaller school-age cohort. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of children under five fell by 1.8 million nationwide, from 20.2 million to 18.4 million.(brookings, the74million)

Researchers were already expecting a gradual enrollment slowdown before COVID-19 arrived. The National Center for Education Statistics projects that even assuming families eventually return to pre-pandemic habits, overall population decline alone will trim public school rolls by approximately 2.2 million students by 2050. White student enrollment had been declining for years, dropping thirteen percent from 2014 to 2023 levels. Black enrollment also fell steadily. Meanwhile, Hispanic and Asian enrollment continued to grow but at slower rates than the previous decade, no longer large enough to offset losses among white and Black students.(brookings, the74million)

Even before the pandemic, charter school enrollment had grown from 2.7 million in fall 2014 to 3.4 million in fall 2019. Homeschooling was also rising, with approximately 3.7 percent of students ages five to seventeen receiving instruction at home in 2019. These trends suggested that families were already seeking alternatives to traditional public schools, albeit at a measured pace.(the74million)

COVID-19: Accelerator, Not Originator

When COVID-19 struck in March 2020, it did not create new problems so much as dramatically accelerate existing ones. The 2020-21 school year saw total public elementary and secondary enrollment decline by three percent between fall 2019 and fall 2020—the largest single-year decline since 1943 and the largest drop since World War II. This erased a decade of steady enrollment growth.(nces, stateline)

The pandemic forced millions of families to rethink where and how their children learn. COVID-19 gave parents an unprecedented window into classroom instruction through remote learning, allowing them to assess whether their pre-pandemic schooling arrangements were adequate. Many concluded they were not. Between 2019-20 and 2021-22, roughly 2.05 million additional students went missing from both public and private enrollment files—a 450 percent jump in “missing” students. Traditional public schools accounted for 1.72 million of that total.(brookings, chalkbeat)

Interest in homeschooling surged from 3.7 percent in 2019 to 11.1 percent of households with school-age children in fall 2020. While many families eventually returned, by fall 2024, homeschooling remained fifty-six percent higher than in fall 2019—fifty percent above predicted levels. Private school enrollment, while slightly below fall 2019 levels in absolute terms, was 15.6 percent above predicted decline based on pre-pandemic trends. The share of children outside public schools entirely averaged 9.7 percent before COVID-19, jumped to 11.5 percent in 2020-21, peaked at 13.1 percent in 2021-22, and remained elevated at 12.6 percent in 2023-24.(brookings, educationnext)

The Fundamental Question: Is the Traditional Model Obsolete?

The acceleration of enrollment decline and the persistent failure to recover academically raise a profound question: is the traditional K-12 education model itself becoming obsolete? Multiple lines of evidence suggest the answer may be yes, or at least that the model requires fundamental transformation rather than incremental reform.

The Rise of Personalized and Alternative Learning

By 2025, families increasingly view traditional one-size-fits-all school models as inadequate for meeting diverse learning needs. A 2023 EdChoice study found that forty-eight percent of parents prefer a hybrid learning model for their children, compared to just forty-one percent preferring full-time in-person learning. Even more striking, seventy percent of students indicated a preference for digital learning models according to a 2023 Tyton Partners report.(accelerationacademies)

Alternative education now offers personalized learning paths that allow students to progress at their own pace, focusing on areas of interest while receiving tailored support where needed. Montessori, Waldorf, Reggio Emilia, project-based learning, and other pedagogical approaches have demonstrated effectiveness for many learners. Microschools—small-scale educational establishments offering more personalized and flexible experiences than traditional schools—are proliferating. Data from Johns Hopkins University’s Homeschool Hub reveals that homeschooling numbers continued growing during the 2023-24 academic year compared to the prior year in ninety percent of states that reported data, shattering assumptions that pandemic-era growth was temporary.(the74million, noveleducationgroup)

The Technology Revolution and Adaptive Learning

The internet and digital learning platforms have fundamentally altered educational possibilities. Students can now learn from anywhere through online courses, interactive simulations, and AI-driven personalized learning programs. Platforms like Khan Academy, Coursera, and Google Classroom provide flexibility that traditional schools often struggle to match. Over thirty percent of students now prefer online learning over traditional classroom settings, drawn by the ability to learn at their own pace and tailor the experience to unique needs.(sjhometuition, askatechteacher)

Adaptive learning technology allows for genuinely personalized education, addressing one of the biggest critiques of traditional schools: their inability to accommodate students who learn at different paces, have unique interests, and excel in different areas. Artificial intelligence in particular poses fundamental challenges to traditional educational models. AI makes possible skill-based learning structures where foundational skills serve as bedrock for more complex skills, replacing passive lecture-based learning with flipped classrooms where skills are independently acquired and then applied to real-world problems during class time.(weforum, sjhometuition)

The Mismatch with Contemporary Skill Needs

The traditional education model was designed to prepare students for an industrial-era workforce, emphasizing memorization and standardized skills. Today’s job market prioritizes creativity, critical thinking, adaptability, and problem-solving—capabilities often better nurtured through project-based learning, collaboration, and real-world application than through rigid classroom instruction. This fundamental mismatch between what schools were designed to produce and what society now requires raises existential questions about the traditional model’s viability.(sjhometuition)

Alternative education providers are responding by focusing on career readiness, partnering with local businesses, trade schools, and community colleges to provide hands-on experience. The lecture-plus-high-stakes-exam model fails to cultivate highly effective learners who can transfer skills from classroom to real world because it treats students as passive consumers of information rather than active learners who must recall and deliberately apply information across both time and context.(weforum)

The Middle School Exodus

Perhaps most tellingly, enrollment data from Massachusetts and other states shows that the post-pandemic exodus has been particularly pronounced in middle schools. Local public school enrollment in Massachusetts middle grades in fall 2024 was down almost eight percent, with the most significant losses concentrated among white and Asian families in high-income communities. These families were more likely to switch to private schools offering in-person instruction during the pandemic, and those shifts appear to have persisted. Elementary grades have largely recovered to predicted levels, and high school enrollment has barely budged, but middle schools are hemorrhaging students.(educationnext)

This pattern suggests that when families have choices and resources, they increasingly conclude that what traditional public schools offer during the critical middle years is inadequate. Whether this reflects dissatisfaction with academic quality, social environment, or developmental approach, the middle school exodus signals that the traditional model is failing to meet family expectations during a crucial educational phase.

The Deep Causes: A Synthesis

Synthesizing decades of research and recent trends reveals several interrelated deep causes underlying the slow, uneven decline of American public schools:

Institutional capture and misaligned incentives: Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, public education governance shifted from parent and community control toward professional educator and union influence. While not inherently problematic, this shift created incentive structures that prioritized adult employment conditions over student academic outcomes. The result was declining academic rigor even as spending increased and class sizes shrank—a productivity decline unparalleled in American institutional history.

Ideological confusion about education’s purpose: The 1970s saw influential research claiming schools didn’t make much difference compared to family background, leading to curriculum debasement and lowered standards. While subsequent research proved schools could significantly impact achievement, the damage had been done. Debates about whether education should emphasize academic knowledge, vocational preparation, social-emotional development, equity outcomes, or other goals have prevented coherent, sustained focus on core learning objectives.

Fiscal constraints and inequitable funding: Tax revolts beginning in the late 1970s permanently constrained education funding in many states, creating growing disparities between well-resourced and poorly-resourced districts. Per-pupil spending varies dramatically across and within states, ensuring unequal educational opportunities. Most state and federal aid flows on a per-pupil basis, creating fiscal stress as enrollment declines—a vicious cycle where declining enrollment leads to budget cuts, which diminish quality, which drives more families away.

Demographic shifts and declining fertility: The U.S. fertility rate has fallen below replacement level, from 1.71 in 2019 to current rates around 1.6—the lowest in American history. This ensures continued enrollment decline regardless of school quality or family satisfaction. The shrinking school-age population concentrates in certain demographic groups while others decline, complicating efforts to maintain stable enrollment.

The one-size-fits-all model in an age of customization: Students have always learned at different paces and excelled in different ways, but technology now makes genuine personalization feasible and affordable. Parents who have experienced customization in every other aspect of their lives—from streaming services to social media to shopping—increasingly question why education should remain standardized. The pandemic gave millions of families their first sustained opportunity to see inside classrooms and explore alternatives, leading many to conclude that traditional schools weren’t meeting their children’s needs.

Stagnant pedagogy in a transforming world: The lecture-and-test model was designed for an industrial economy requiring workers who could follow instructions, perform repetitive tasks, and operate within established systems. The modern economy requires creativity, problem-solving, collaboration, and continuous learning—capabilities that passive, standardized instruction doesn’t reliably produce. This mismatch grows more apparent as the economy transforms and employers report that graduates lack needed skills.

Loss of trust and polarization: COVID-19 school closures, debates about curriculum content, book bans, and culture-war battles have severely damaged trust between families and public schools. PEN America documented 6,870 school book bans during the 2024-25 school year, describing censorship as “rampant and common.” Political polarization has fractured the bipartisan education reform consensus that existed from the 1980s through much of the Obama administration, replacing it with red-state and blue-state approaches that often seem designed more to signal tribal affiliation than improve learning.(pen.org, fordhaminstitute)

Conclusion: The Path Forward Requires Fundamental Rethinking

The evidence is clear: the decline of American public schools predates COVID-19 by decades and has roots extending back to the late 1960s. While the pandemic accelerated enrollment losses and learning deficits, it exposed and intensified pre-existing structural problems rather than creating new ones. The question is no longer whether traditional public schools are in decline but whether that decline represents an existential crisis requiring fundamental transformation.

If families continue choosing alternatives at the pace observed since 2020, traditional public schools could lose as many as 8.5 million students by 2050, shrinking from 43.06 million in 2023-24 to as few as 34.57 million by mid-century. Even if families return to pre-pandemic habits, population decline alone will trim public school rolls by about 2.2 million students.(brookings)

The traditional K-12 model is not necessarily obsolete, but it requires transformation to remain viable. This means moving beyond the factory model of standardized instruction toward genuinely personalized learning that leverages technology and human expertise. It means restructuring governance to align incentives with student outcomes rather than adult employment conditions. It means rethinking funding mechanisms to address equity while maintaining quality. It means rebuilding trust between schools and communities through transparency and responsiveness to family needs.

Most fundamentally, it means acknowledging that incremental reforms have failed to address deep structural problems over fifty years. The slow, uneven decline documented in the 2026 ETC Journal article reflects accumulated institutional dysfunction, demographic realities, and technological disruption that require responses commensurate with the scale of the challenge. Without such responses, the decline will likely continue and perhaps accelerate, leaving American public education as an increasingly marginalized option for families who have no alternatives.

The task ahead is not simply to restore public schools to some imagined past glory—the evidence suggests that past was less glorious than nostalgia suggests—but to reimagine public education for a world transformed. That reimagining must grapple honestly with why the current model is failing so many students and families, and must be willing to consider fundamental changes to structure, governance, funding, and pedagogy. Anything less ensures that the slow, uneven decline will continue unabated.

Epilogue

The 1967 achievement peak—that moment before the long decline began—came at a time when we still thought we were on an upward trajectory. The subsequent fifty-plus years have been characterized by increasingly expensive attempts to return to a baseline that, upon closer examination, was never as strong as we believed.

The data reveals something profoundly challenging: we’ve been trying to fix a system that may have been fundamentally misaligned with student needs even during its supposed golden age. The factory model worked well enough for an industrial economy, but it’s unclear whether it ever truly served the full range of human learning potential—and it’s certainly inadequate for today’s world.

Most sobering is the realization that each wave of reform—from “A Nation at Risk” through No Child Left Behind to more recent efforts—addressed symptoms while leaving the deep structural problems untouched. The institutional capture, misaligned incentives, one-size-fits-all pedagogy, and governance dysfunction have persisted across decades of supposed reform.

Looking beyond the immediate crisis to the long arc of decline suggests that the current moment may actually be an opportunity—families voting with their feet, technology enabling genuine alternatives, demographic pressures forcing hard choices—to finally attempt the fundamental reimagining that incremental reforms have failed to achieve.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment