By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Perplexity)

Editor

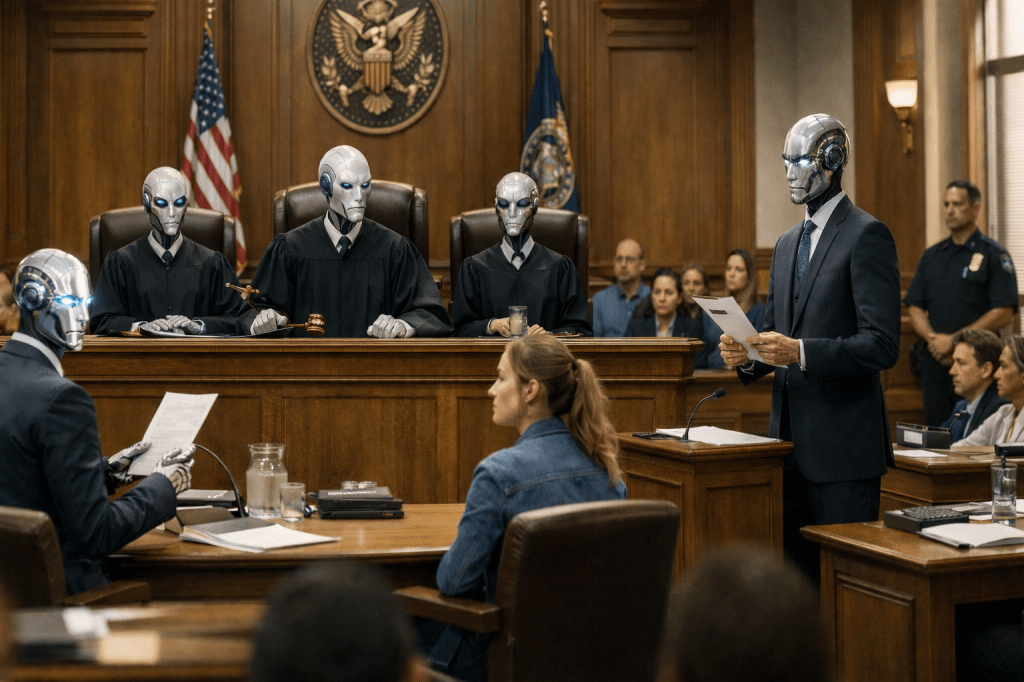

In a future where routine state and federal cases run almost entirely on AI, the transformation will have required deep, coordinated changes in both technology and law. This future would emerge not from a single breakthrough, but from a layered re-engineering of data, doctrine, institutions, and public expectations.[yalelawjournal, NCSC, OECD]

From Decision-Support Tools to De Facto AI Adjudication

The starting point is today’s “weak” use of AI in courts: tools for document processing, transcription, basic analytics, and chatbots that answer procedural questions. Over time, these tools must evolve from peripheral helpers into core processors of cases, progressively handling more complex legal reasoning and factual analysis.[ncsc, OECD]

First, AI systems would have to become capable of consistently mapping messy, layperson narratives into legally relevant issues and claims, a task current “self-help” chatbots only partially achieve. These systems would learn to: identify causes of action, match facts to elements of claims and defenses, and generate pleadings, motions, and settlement proposals in standardized formats. Second, AI would need robust capabilities in evidence handling—ingesting documents, recordings, and sensor data, assessing credibility through cross-source consistency rather than unreliable proxies like demeanor, and constructing structured “case graphs” that link facts, law, and potential outcomes.[yjolt, yalelawjournal]

At a later stage, AI tools that now serve judges as knowledge systems—organizing precedents, statutes, and voluminous files—would cross the line from recommendation to default decision, with human judges intervening mainly in outlier or escalated cases. This migration from decision-support to de facto automated adjudication would not be announced as a single moment; instead, thresholds would shift quietly as courts trust AI outputs enough to adopt them by presumption, only rarely overriding them.[oecd, stimson]

Data, Interoperability, and the Infrastructure of “Machine-Readable Justice”

Nothing approaching fully AI-run lower courts is possible without transforming legal data into a standardized, interoperable infrastructure. A critical precondition is that statutes, regulations, judicial opinions, dockets, and filings become machine-readable at scale, with rich metadata about issues, parties, procedures, and outcomes.[yalelawjournal, stimson]

Current work on interoperable legal AI for access to justice already emphasizes the need for standardized court data, open-source components, and shared taxonomies so that tools can “talk to” heterogeneous court systems. This would need to expand dramatically. Dockets, pleadings, motions, evidentiary rulings, and judgments would be expressed in structured formats that encode:[yalelawjournal]

- the procedural posture of each case,

- the legal issues presented, and

- the logical structure of the court’s reasoning.

Large-scale projects to systematically analyze litigation data—such as efforts to build open knowledge networks of who is prosecuted, for what, and with what outcomes—preview this direction. Over time, such initiatives would need to be generalized and embedded as mandatory infrastructure: every court filing becomes both a document and a data event.[yalelawjournal]

Interoperability also has a governance dimension. Courts and regulators would have to adopt standard APIs, certification processes, and logging requirements so multiple AI providers can operate reliably across jurisdictions without fragmenting the system. Brazil’s “Justice 4.0” and similar programs, which treat digitization, interoperability, and AI as part of a unified transformation agenda, illustrate how large, complex judiciaries can coordinate such change.[oecd, yalelawjournal]

Rewriting the Rules on the Practice of Law

Today’s unauthorized practice of law (UPL) rules are a primary legal barrier to free, AI-based representation at scale. These rules typically restrict legal advice and representation to licensed human attorneys and have been used to chill legal-tech innovation. To reach a world where “legal services are provided free to everyone” by AI, jurisdictions would need to:[thomsonreuters]

- Narrow UPL definitions or explicitly confine them to human actors, clarifying that AI systems, as tools rather than persons, do not themselves “practice law.”[thomsonreuters]

- Create regulatory sandboxes where AI legal services can operate under supervision, enabling experimentation while data is gathered about safety, effectiveness, and bias.[thomsonreuters]

- Develop new licensing or accreditation categories for AI systems (and their developers) that tie market access to performance metrics, transparency, and alignment with ethical standards.

Contemporary debates already highlight the “personhood gap”: AI lacks legal personhood and thus cannot commit UPL, but the corporations providing AI can be targeted, creating uncertainty that discourages innovation. Over time, legislators and courts would craft clearer responsibility frameworks that regulate human and corporate actors behind AI tools, while allowing the tools themselves to deliver advice and representation directly to lay users.[techreg, yalelaw, thomsonreuters]

This evolution would likely be pushed by access-to-justice imperatives. The massive gap between legal needs and available human lawyers has long motivated calls to democratize legal information. As AI proves capable of handling routine matters safely, political and professional resistance to machine-delivered legal help would weaken, especially if evidence accumulates that AI tools reduce errors, improve consistency, and expand access.[yjolt, yalelawjournal]

From Online Dispute Resolution to Fully Automated Proceedings

The procedural architecture of courts would also need to shift toward digital-first and, ultimately, AI-centric designs. Online dispute resolution (ODR) already shows how much of civil justice—especially in high-volume, low-stakes domains—can move out of physical courtrooms into online platforms.[ncsc, yalelawjournal]

In the envisioned future, ODR would evolve from simple web portals into comprehensive, AI-driven environments that:

- guide users through intake via conversational interfaces,

- automatically identify claims, defenses, and relevant evidence,

- propose negotiated settlements using optimization models calibrated to legal norms and historical outcomes, and

- escalate only unresolved or complex disputes to formal adjudication.

Many cases would never “go to court” in the traditional sense; instead, they would be resolved in virtual negotiation rooms where AI agents representing each party bargain under constraints derived from law and policy. Current experiments with AI-enabled litigant portals and guided interviews foreshadow this, but future platforms would be far more capable and deeply integrated with court back-ends.[ncsc, ncsc, oecd]

For disputes that proceed to adjudication, AI would manage scheduling, service of process, discovery timelines, and motion practice, enforcing standardized procedures that minimize delay and variation. Hearings—if any—might be brief, remote, and heavily scripted by AI, which would have already identified key factual disputes and legal issues, prepared questions, and produced draft decisions. Human judges in lower courts would become rare, focused on oversight, exceptional cases, or quality control audits.[ncsc, oecd]

Transparency, Fairness, and the Re-Engineering of Due Process

Automating most of the justice system would force a reconceptualization of procedural fairness. The traditional pillars—notice, an opportunity to be heard, and an impartial decision-maker—would have to be translated into algorithmic guarantees. Evidence from current deployments shows that opaque decision systems can threaten due process and anti-discrimination norms, heightening concerns about transparency and contestability.[yalelawjournal, oecd]

Several shifts would therefore be necessary:

First, explainability and auditability would become non-negotiable design requirements. Legal scholars already emphasize that AI systems influencing liberty, eligibility, and access must be amenable to scrutiny for bias, error, and rights violations. In an AI-dominant court, this would be operationalized through mandatory logging of reasoning paths, structured explanations of how facts and legal rules produced outcomes, and rights to obtain machine-readable decision records that can be reviewed or appealed.[techreg, yalelawjournal]

Second, due process rights would be updated to include the right to a meaningful human review in certain categories of cases (e.g., criminal, family, or immigration), even if the default adjudicator is an AI system. Legislatures and courts would specify which matters require human oversight, and at what stage, ensuring that people can still access human judgment when stakes are existential or norms are contested.[yalelawjournal, oecd]

Third, fairness would be monitored at scale using the very data infrastructure that enabled AI adjudication. Interoperable court systems could be mined to reveal systemic disparities—who is prosecuted, what penalties are imposed, and how patterns vary across demographic lines—allowing continuous recalibration of AI models and legal standards. Large, national platforms that aggregate litigation data already aim to uncover such patterns, and in the future they would be integral to both governance and model governance.[oecd, yalelawjournal]

Constitutional and Institutional Realignments

For AI to handle “the vast majority” of cases, constitutional doctrines and institutional roles would need to adapt. Current legal frameworks often assume human judges as central figures, especially in areas implicating fundamental rights. The gradual shift would likely occur via:

- incremental judicial decisions upholding the use of AI in specific procedural domains (e.g., sentencing recommendations, bail risk assessments, or administrative adjudication), provided safeguards are in place;

- legislation that explicitly authorizes AI-managed procedures, defines their limits, and sets standards for transparency and appeal; and

- institutional redesign in which human judges focus on meta-level oversight, norm-setting, and interpretation of constitutional questions, rather than day-to-day fact-finding.

Debates over AI legal personhood capture some of the conceptual pressure this transformation exerts. Although most scholars currently argue against granting full legal personhood to AI, they highlight how increasing cognitive capabilities force courts to revisit concepts like agency, responsibility, and rights. Even without recognizing AI as “persons,” courts would need doctrinal tools to attribute decisions, allocate liability for errors, and ensure that constitutional obligations are met in a system where the human judge is no longer the primary decision-maker.[yalelawjournal]

Supreme courts—state and federal—would remain human-led but heavily augmented. Human justices would rely on AI to generate briefs, synthesize precedents across centuries, simulate the downstream effects of alternative rulings, and test doctrinal consistency across domains, but the authoritative interpretive act would remain human. These apex courts would, in effect, be guardians of a hybrid system, ensuring that the automated lower tiers remain within constitutional bounds and updating those bounds as society and technology co-evolve.[stimson, yalelawjournal, oecd]

Economic and Policy Shifts to Free, Universal Legal Services

Finally, making legal services free for everyone requires economic and regulatory reforms as profound as the technological ones. The current access-to-justice gap reflects the high cost of human legal labor and the limited supply of lawyers willing or able to serve low-income clients. AI changes this calculus by offering near-zero marginal cost legal assistance once systems are built and maintained.[adr, yjolt, yalelawjournal]

Policy makers would have to decide to treat core AI legal infrastructure as a form of public utility or public good. This could take several forms: direct public provision (government-built, open-source systems), heavily regulated private provision with mandated free tiers funded by subsidies or cross-subsidization, or hybrid models that blend public platforms with certified private modules. Interoperability and open standards would again be crucial to prevent monopoly control and to ensure that tools remain accessible, especially for marginalized communities.[oecd, yalelawjournal]

Concerns about creating an inequitable “two-tiered” system—where wealthy clients get bespoke human advice and the poor get only automated guidance—already surface in discussions of AI justice. In the imagined future, that risk is turned around: if AI adjudication becomes demonstrably more accurate, faster, and fairer than overburdened human systems, denying AI assistance could itself be seen as a form of inequality. Legal and ethical frameworks would need to guarantee that high-quality AI representation is available to all, while preserving avenues for human counsel where necessary.[yjolt]

In this trajectory, the end state—largely automated lower courts with free AI representation—does not arrive by fiat. It emerges from decades of intertwined developments: the standardization and opening of legal data; the maturation of AI from tool to default decision-maker; the loosening and redefinition of professional monopolies; the digitization and algorithmic redesign of procedure; new doctrines of transparency, fairness, and accountability; and deliberate policy choices to treat access to legal help as an infrastructure problem rather than a boutique service.[stimson, ncsc, yalelawjournal, ncsc, yjolt, thomsonreuters, yalelawjournal, oecd]

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment