By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by Claude)

Editor

Marshall McLuhan’s theory that “the medium is the message” offers a useful lens for understanding AI in 2025-2026, revealing that we are experiencing not merely a new tool but a fundamental restructuring of human cognition itself. McLuhan’s central insight was that the form of a medium matters more than its content—that television, for instance, reshaped how people interpreted truth and experienced time regardless of what programs aired. Applied to AI today, this means we must look beyond what AI produces and examine how its very existence is transforming our mental architecture. As scholars writing in 2025 have observed, AI represents what they call “a structural break” from analog to digital to cognitive, where the medium no longer simply influences cognition from outside but operates alongside us, perhaps even inside our thinking processes. Unlike McLuhan’s television or telephone, which extended our senses, AI extends ideation itself—it becomes, in the words of contemporary analysis, “an intellectual presence with its own style of synthesis and fluency.” (psychologytoday.com)

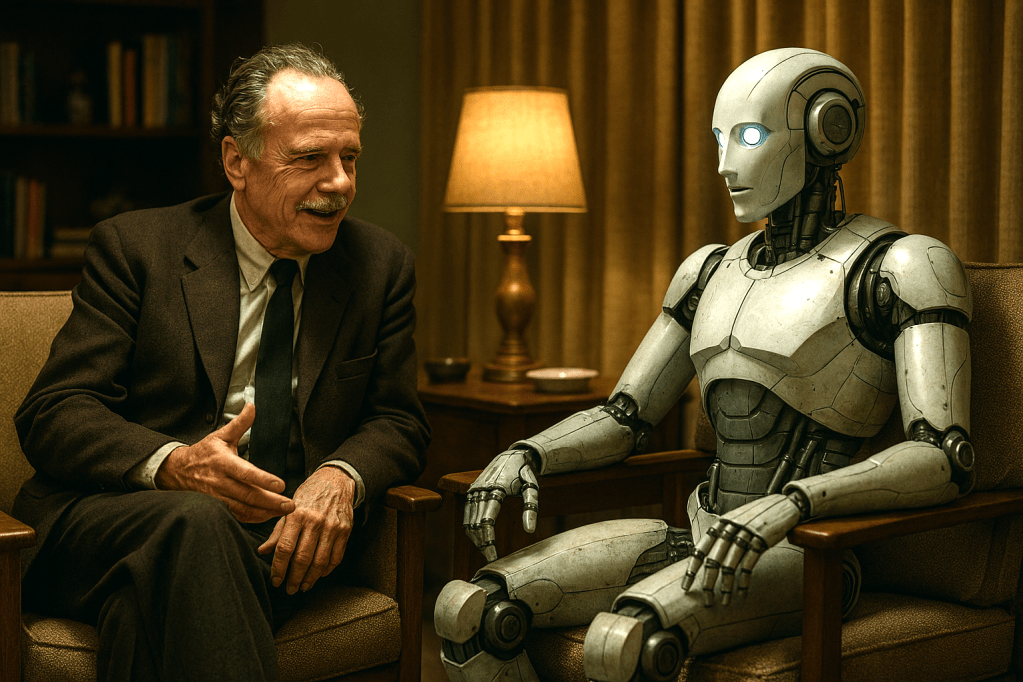

The most significant insight McLuhan’s framework provides is recognizing that we are swimming in waters we cannot yet see, much like his famous fish analogy. As Grant Havers argues in a 2025 examination of McLuhan’s continuing relevance, new media create environments that are initially invisible to people, and we discover their hidden effects only after they have taken root in civilization. This is precisely our situation with AI: we debate its content outputs—whether text is accurate, whether images are authentic—while missing the deeper transformation occurring in how we think. Research published in 2025 suggests that AI is becoming what scholars term “a co-creator, a cognitive environment, and an autonomous participant in meaning-making,” operating not as a neutral tool but as an active medium that shapes the very formation of ideas. The danger McLuhan would identify is that when AI’s responses arrive with such authority, they become easy to treat as extensions of our own reasoning rather than something separate, and AI’s cadence may even overshadow the slower, more generative processes of human thought. (preprints.org; psychologytoday.com)

Viewing AI through McLuhan’s lens also illuminates what a 2025 analysis describes as the fundamental shift in the message AI delivers: efficiency over introspection, scale over subtlety, and synthesis over disruption. Generative AI excels at producing what we expect, recombining prior forms into dazzling outputs, but this very capability conditions us to accept the familiar rather than leap into the unknown. The medium’s message becomes optimization rather than transformation—pursuing “better” instead of “different,” “efficient” rather than “meaningful.” This connects directly to McLuhan’s warning about the numbing effect of technology. As scholars writing in 2025 have recognized, AI creator Sam Altman and other Silicon Valley figures have been absorbed into the McLuhanesque message of their own creations, subscribing to visions of consciousness transfer and human-machine merger that demonstrate they’ve forgotten that brains are connected to bodies. McLuhan would have seen this as the classic pattern: technologists becoming servomechanisms of their own extended image, losing self-awareness in the reflection. (mmg-1.com; editorstorontoblog.com)

Perhaps most crucially, McLuhan’s framework helps us understand AI’s role in cognitive offloading and what recent scholarship identifies as the blurring of support and substitution. Studies from 2025 examine how AI enables cognitive offloading—the delegation of cognitive tasks to external resources to reduce mental demand—but this creates a paradox where the same technology marketed as supporting wellbeing may actually weaken intrinsic coping mechanisms. A mood-tracking app, for instance, doesn’t merely record feelings; it interprets and quantifies them, often presenting its interpretation as more authoritative than subjective experience. McLuhan’s theory reveals this as the medium exercising its inherent effect: AI doesn’t just help us think—it changes what thinking means. The challenge, as contemporary researchers frame it, is recognizing when the system shapes our reasoning versus when it substitutes for the slow, formative work that remains uniquely human—curiosity, intuition, hesitation, the gradual accumulation of understanding. (frontiersin.org)

McLuhan would likely point to another dimension we’re only beginning to recognize: that AI is creating what recent scholarship calls “cognitive echo chambers” where dissent is discouraged and reinforcing feedback loops dominate. While McLuhan predicted the “global village” would retribalise humanity through electronic media, AI takes this further by personalising each person’s information environment so completely that we may be creating not a shared village but millions of individual bubbles. This connects to McLuhan’s concept of “discarnate being”—when we’re interfacing with AI, we lack physical presence, becoming what a 2025 article describes as porous, with light and message going right through us, depriving people of their identity. The philosopher John Nosta captured the essential McLuhanian insight for our moment: earlier media influenced cognition from outside, but today’s cognitive systems operate alongside us or perhaps even inside us, meaning AI has moved beyond being channels or platforms to becoming a counterpart. McLuhan mapped the environment; our task is mapping the partnership—and the measure of our success may be preserving the friction of thought that remains uniquely human. (preprints.org; slate.com; psychologytoday.com)

Finally, McLuhan’s theory illuminates why the most important conversations about AI are the ones we’re not having. As education scholar Gordon Gow observed in June 2025, McLuhan predicted that automation would make the liberal arts mandatory rather than obsolete, because in an age where machine intelligence is integrated into communication and creativity, the humanities become more essential than ever for cultural understanding, ethical reasoning, and imaginative expression. The real danger isn’t AI replacing us—it’s what McLuhan illustrated through the Narcissus myth. Narcissus didn’t fall in love with himself; he mistook his reflection for someone else and became the servomechanism of his own extended image. We risk becoming passive users of our technological extensions, allowing them to shape how we think without realising it. McLuhan’s framework demands we ask not “what can AI do?” but rather “what is AI doing to us?”—how it’s restructuring attention, reorganizing knowledge, and redefining what it means to think, create, and be human. The medium of AI is already delivering its message; the question is whether we’re conscious enough to read it. (theconversation.com)

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Leave a comment