By Jim Shimabukuro (assisted by ChatGPT)

Editor

Introduction: I prompted ChatGPT: Get me up to speed on Elon Musk’s and Jeff Bezos’ outlooks for future space colonies. For each, explain their plan, rationale, initial steps, why it matters to the rest of us, time frame to launch, major obstacles, and your opinion on the ultimate value and probability for success. Follow-up prompts: (1) Is there a 3rd vision re future space colonies lurking in the background that we should be aware of? If yes, please explain. (2) In the Musk-Bezos vision, humans are a central focus. Are they (or anyone else) considering the possibility of focusing on AI robots instead of humans, and what are the advantages/disadvantages of robots? Following are ChatGPT’s responses. -js

Elon Musk — the Martian Gambit

Elon Musk’s vision for human settlement beyond Earth is unambiguous: make humanity a multiplanetary species by building a transport system capable of routinely moving people and cargo to Mars, and then scale that system until a self-sustaining city exists there. The technical centerpiece of the plan is SpaceX’s Starship — a fully reusable, super-heavy launch stack designed to radically lower the marginal cost of moving mass to orbit and beyond. SpaceX publicly frames Starship as the vehicle that will enable the first uncrewed and crewed Mars missions, with the company’s materials and timeline repeatedly pointing to near-term test flights followed by increasingly ambitious cargo and crew flights to Mars. SpaceX’s own Mars materials and recent program updates make clear that Starship is intended to do the heavy lifting for any Martian colony effort. (SpaceX)

Musk’s rationale blends existential and practical arguments. Existentially, he repeats the argument that spreading humans across worlds is insurance against planetary catastrophe. Practically, he argues that lowering launch cost per ton through full reusability will make the transport economics feasible: if rockets can be reused like airplanes, then shipping people and the enormous quantities of equipment needed for habitats, fuel production, and life support becomes a tractable engineering and economic problem. Musk also frames the project as a long, iterative engineering program: first prove orbital reusability, then large-scale orbital refueling, then repeated cargo runs timed to favorable Earth–Mars transfer windows. Over time, he has stated extremely ambitious numerical goals — for example suggesting the possibility of sending one million people to Mars by mid-century — though he has allowed that such figures are aspirational. (Wikipedia)

Initial steps SpaceX has taken are visible and concrete: repeated high-altitude and suborbital Starship prototypes, full-scale static fires and orbital launch attempts, progressive iteration on heat shields, Raptor engine variants, and development of orbital refueling and ground infrastructure at Boca Chica (Starbase). SpaceX’s cadence is “test, learn, redesign” at a scale few organizations can match, and that momentum is why even skeptical analysts give SpaceX a nontrivial shot at achieving the first milestones — low-cost orbital reusability and a first uncrewed Mars payload — within the next decade. Recent program updates and independent reporting show ongoing iterative flight tests and a schedule that remains optimistic but active. (SpaceX)

Why this matters to the rest of us goes beyond romantic images of red deserts. Technically, the push to master large, reusable launchers and in-space refueling will compress costs for many space activities: satellites, science missions, and infrastructure in Earth orbit could all benefit. Economically, if large volumes of mass can be moved off Earth affordably, new industries (space manufacturing, large solar power arrays, asteroid resource extraction) become conceivable. Politically and culturally, a credible path to Mars forces society to grapple with space governance, planetary protection, and whether opening a near-frontier will replicate the inequalities of earlier Earthly expansions or engender more cooperative institutions. Musk’s program therefore functions as both a technical project and a forcing function for public debate about who benefits from space development. (Aerospace America)

Timeframes are contentious. Musk has repeatedly offered aggressive schedules — sometimes predicting crewed flights within a handful of years — while independent analysts and Aerospace/AIAA reporting temper those estimates, showing that regulatory, engineering, and production realities often push dates outward. SpaceX’s stated program milestones have included first uncrewed Mars-targeted flights (originally framed for the mid-2020s transfer window) and progressively later crewed flights; at the same time, industry specialists note that realistic timelines for a self-sustaining settlement span decades, not years. So while the first cargo and crewed demonstrations might occur within one Mars launch-window or two if everything goes well, turning that into a self-sustaining city is plausibly a multi-decadal undertaking. (Aerospace America)

The obstacles are enormous and layered. At the engineering level, Starship must achieve high-rate, high-reliability reusability (including thermal protection and controlled reentry) and demonstrable orbital refueling capability. Once landed, Martian settlers will face thin atmosphere, intense cosmic and solar radiation, extreme dust, low temperatures, and a lack of readily accessible liquid water on the surface. Creating in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) facilities that can reliably produce oxygen, water, and methane fuel at scale is a monumental challenge. Beyond technical hurdles are financial and organizational obstacles: building and operating the necessary industrial base on Mars requires capital, skilled labor, and supply chains that no company can provide alone. Finally, ethical, legal, and geopolitical questions — who owns what on Mars, what stewardship obligations exist toward a planet that might host life, and how to share benefits — will be fiercely debated. Critics also point out the risk of concentrating enormous power in a private company, raising governance concerns. (Wikipedia)

My assessment of the ultimate value and probability of success is a mix of guarded optimism and realism. The technological value is high: even partial success would produce capabilities (cheap heavy lift, rapid reusability) that transform space operations on Earth and in orbit. The existential rationale is harder to operationalize: while a multiplanetary species is a desirable long-term hedge, the near-term human and economic returns are uncertain.

Probability-wise, I give SpaceX a strong chance of delivering the key enabling technologies (reusable heavy lift, some Mars demonstration payloads) within the next one to two decades, because the company has repeatedly demonstrated rapid iteration and mission focus. The probability that Musk’s loftiest societal goals — a self-sustaining, populous Martian city within a few decades — will be realized on his original timelines is low; but the probability that he will push humanity several meaningful technical steps closer to that vision is substantially higher. In short: high technical upside, meaningful near-term wins likely, but full colonization within Musk’s shortest timeframes remains improbable without other global investments and institutional cooperation. (SpaceX)

Jeff Bezos — the Orbital Industrial Ecosystem

Jeff Bezos’s outlook on space emphasizes infrastructure first and human presence second, but at vastly larger scale and in a different form than Musk’s Mars gambit. Bezos champions moving heavy industry off Earth and building vast rotating habitats — O’Neill-style cylinders — where millions could live and work, powered by space’s abundant solar energy and supplied by orbital manufacturing and in-space logistics. Bezos frames this as a way to preserve Earth: move industrial activity and energy harvesting off the planet so Earth’s environment can recover while humanity expands into the abundant volume of near-Earth space. Blue Origin’s public messaging, and Bezos’s repeated comments, underscore the image of “millions of people” eventually living and working in space. (Blue Origin)

Bezos’s plan is more infrastructural and market-centric than Musk’s: rather than a single rush to settle a specific planet, he envisions layered capability building — reusable orbital and suborbital launchers (New Glenn, and earlier New Shepard), lunar logistics (Blue Moon lander work), commercial low-Earth orbit destinations (the Orbital Reef concept in partnership with Sierra Space and others), and eventually large, privately constructed habitats leveraging asteroid and lunar resources. The phrase “millions living in space” signals scale, but the path there runs through many incremental markets: government launches, satellite deployment, space tourism, commercial research and manufacturing in microgravity, and then mixed-use orbital destinations that bootstrap larger ecosystems. Blue Origin presents this as a long-term commercial ecosystem rather than a singular national or corporate colony. (Blue Origin)

The initial, tangible steps Blue Origin has taken are pragmatic: continue developing New Glenn — a heavy-lift vehicle intended to compete in commercial and national security launch markets — mature engines and upper stages, test lunar lander elements, and participate in commercial space station efforts like Orbital Reef with industry partners. New Glenn’s recent launch attempts and progress toward operational flights are important because they test the fundamentals of reusability, scale, and market viability. Orbital Reef, meanwhile, represents a bet that there will be a market for mixed-use LEO destinations for research, manufacturing, and tourism. These steps are incremental and commercially framed rather than grandly visionary in the short term. (Spaceflight Now)

That difference matters because Bezos’s vision shifts the emphasis from a heroic leap to distributed industrial development. If he’s right, the consequences for Earth could be profound: large-scale space economies could relieve some industrial burden on Earth, unlock new energy sources (space solar), and create economic opportunities distributed across firms and nations. However, critics ask whether the economics of moving heavy industry off Earth can overcome the enormous initial capital and operational costs, and whether the social and political will exists to make that transition. As with Musk, questions of governance and equity are central: who owns orbital habitats, how are the benefits distributed, and what regulations will govern these new spaces? (Blue Origin)

Timeframes for Bezos’s “millions in space” are typically longer than Musk’s most optimistic Mars timelines. Bezos has suggested major expansion within a few decades in public remarks, and some recent interviews reiterate ambitious multi-decade growth expectations. But Blue Origin’s programmatic cadence — first to prove New Glenn, then to advance lunar logistics and LEO destinations, and then scale up to full habitats — implies a multi-decadal realization under the best circumstances. Commercial partners (Sierra Space, others) and government contracts will shape the near-term windows. Orbital Reef and comparable station efforts target the coming decade for initial capabilities, not immediate mass migration. (Fortune)

Obstacles mirror Musk’s in scale but differ in kind. The economic challenge of building large habitat structures and moving raw materials off Earth is enormous; it requires sustained private capital, evolving markets for in-space manufacturing, and likely government support. Technical challenges include large-scale life-support in rotating habitats, radiation shielding, and the logistics of moving bulky materials from the Moon or near-Earth asteroids. Blue Origin’s organizational challenges — the company has faced program delays, regulatory probes, and workforce adjustments — also matter; the success of an industrial ecosystem depends on many reliable commercial players, not a single company. Moreover, unknowns in demand (will manufacturing or solar power in space be cost-competitive?) create commercial risk. (Reuters)

In my judgment, Bezos’s vision is valuable in that it reframes space development as infrastructure and industry rather than frontier heroics. That framing increases the chance that space becomes integrated into global economic systems rather than a set of prestige projects. The probability of realizing some elements of Bezos’s vision — operational heavy-lift vehicles, commercial LEO destinations, lunar logistics — is relatively high within a couple of decades because those are concrete markets with existing customers.

The probability of achieving the ultimate, grander vision (millions living in rotating orbital habitats) is far lower on mid-century timescales because it depends on breakthroughs in cost, demand, and materials supply that haven’t yet occurred. Nonetheless, Bezos’s approach may produce broader short- and medium-term public benefit because it aims to build markets and infrastructure that multiple actors can use. If successful, that could make space development less dependent on the fortunes or whims of any single entrepreneur. (Sierra Space)

Both men are betting their fortunes on space, but they place different strategic chips. Musk wagers on speed and a single audacious goal — a city on Mars — to change humanity’s condition; Bezos wagers on layered infrastructure and distributed markets to create an off-Earth industrial civilization. Both paths are hard; both could yield powerful technological spillovers for life on Earth. Which is “better” depends on what you value: the inspirational, high-risk leap that could reshape human destiny, or the quieter, maybe more pluralistic build-the-platform approach that could gradually weave space into the global economy. Either way, the next two decades will tell whether these billionaire visions become islands of private power, engines of public benefit, or a messy combination of both.

A Third Vision: A Government-and-International-Partner-Led Roadmap

Short answers first: Yes, there is a prominent “third” vision — public-led, rules-based, lunar-and-cislunar ecosystem focused on science, diplomacy, and distributed infrastructure — you should be aware of, and both the Musk/Bezos camps (and many other actors) are actively thinking about robot-first approaches as practical complements or alternatives to human-first colonization. Below I unpack both points in plain language.

Alongside Musk’s audacious Mars-first push and Bezos’s long, industrial vision for orbital habitats, a robust third model has been developing: a government-and-international-partner-led roadmap that treats the Moon and cislunar space (the region between Earth and the Moon) as the practical near-term arena for building durable, rules-based space infrastructure. This approach emphasizes scientific exploration, incremental capability building, and multilateral governance rather than heroic private conquest or purely market-driven scale-up.

The logic is straightforward: the Moon is close, has frequent launch windows, well-understood environmental challenges relative to Mars, and resources (regolith, possible polar ice) that can be used for learning how to live off-world. It therefore becomes the natural place to develop technologies and business models — in-situ resource utilization, lunar logistics, power systems, and surface habitats — that could be exported to other destinations later

What distinguishes this third path is its emphasis on shared norms, public funding to de-risk early infrastructure, and multi-stakeholder partnerships that intentionally include academic institutions, smaller commercial players, and international space agencies. Instead of one company pushing a single architectural winner, the model aims to create interoperable infrastructure: logistics hubs, refueling depots, science campuses, and orbital platforms that many actors can use. That lowers entry barriers for research and commerce, spreads costs and risks across nations and firms, and foregrounds governance questions — who has access, how do we protect potential lunar science or life, and how are benefits distributed? For those worried about concentration of private power, this third vision offers a route where public interest, treaty obligations, and open scientific access are central design criteria.

Why this matters is also practical: by solving immediate engineering and policy problems in cislunar space, the international approach can generate scientific returns, sustain a workforce, and establish legal and cooperative frameworks before huge investments lock in single actors’ models. In time, commercial markets seeded by publicly supported demand (science missions, telecom, lunar construction) could scale into broader economic ecosystems without requiring the mass human migration that Musk talks about or the industrial relocation Bezos imagines — at least initially. So the third vision is not mutually exclusive with the others; it’s a complementary, perhaps more politically palatable and risk-averse route to durable capabilities.

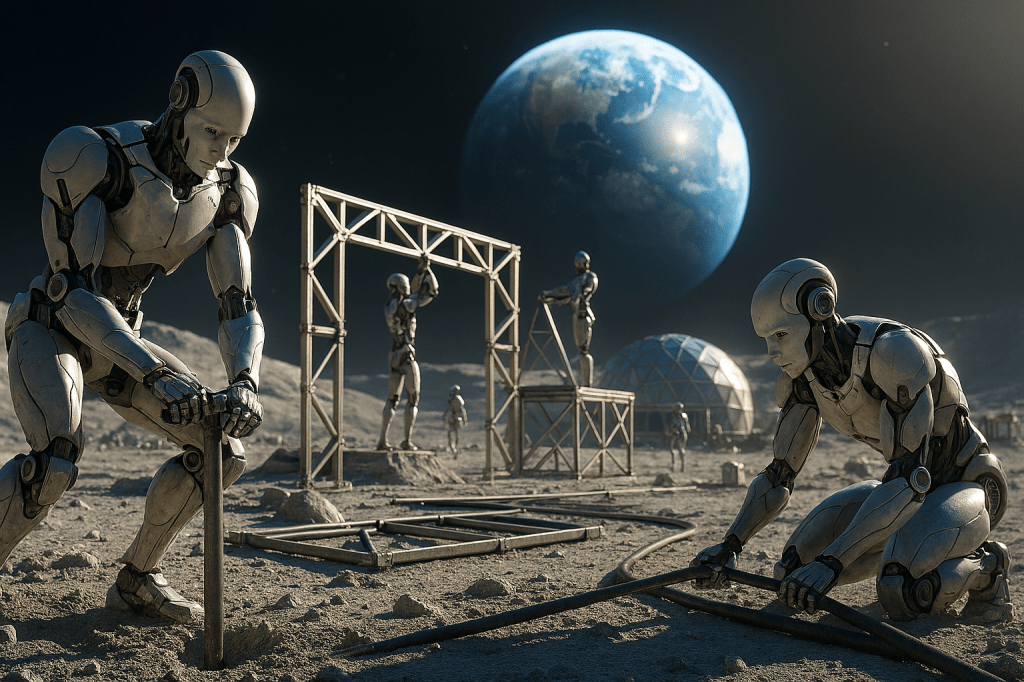

Robots as the First Wave of Settlers

Serious thinking has been underway across academia, government labs, and industry about whether robots — not humans — should be the first wave of settlers, or even the primary long-term inhabitants of off-Earth infrastructure. There are multiple reasons this is attractive. Robots avoid the massive life-support, radiation shielding, and psychological care burdens that come with human passengers. They can operate in hazardous environments and endure long periods without resupply.

A robotic industrial fleet could assemble structures, do mining, and run factories before any human step foot on site, thereby dramatically reducing early mission risk and cost. Robots can also be highly specialized, scaled cheaply relative to sending humans and their consumables, and—in principle—networked to collaborate at planetary scale on tasks like habitat construction, resource extraction, and manufacturing.

There are, however, significant disadvantages and deeper complications. Robots still need supplies, maintenance, and robust autonomy. Mechanical systems fail; spare parts and repair infrastructure must be shipped or manufactured in-space. Autonomy under unstructured, dusty, and unpredictable planetary conditions is still an unsolved systems problem at the scale required. There are also economic and political downsides: a robot-first strategy may concentrate control of off-Earth manufacturing and resources in the hands of a few firms that own and operate the fleets, potentially repeating terrestrial inequities. Ethically and philosophically, relying on robots forecloses human experiences that many value — the idea of humans living and learning in new worlds — and raises cultural questions about what colonization even means if there are no human communities.

Finally, the specter of weaponized robotics and dual-use technology cannot be ignored. Highly capable, mobile robotic systems operating in space could be repurposed for military tasks or create geopolitical instability unless governance mechanisms keep pace. There is also a social risk: if vast robotic industries provide most of the economic value off-Earth, the incentives for bringing people there might diminish, turning space into a distant, mechanized extraction zone rather than a new home for humanity.

Robots as advance teams with humans as settlers and stewards form a pragmatic hybrid. This is the most realistic near-term architecture: dense fleets of robots operate as the advance workforce that builds, mines, and constructs, while humans follow later as designers, maintainers, and community builders. Robots do the heavy lifting under conditions that are lethal or expensive for humans, and humans provide high-level problem solving, cultural development, and governance that machines do not. Telepresence and telerobotics further blur the distinction: human operators on Earth or in cislunar orbit can control or supervise robots on the surface, getting many benefits of human oversight without the immediate life-support cost.

My judgment is that robot-first strategies are highly likely to play a central role in how any off-Earth economy develops. They are technologically sensible, economically compelling for early industrial tasks, and politically attractive because they reduce human risk. But robots are not a wholesale substitute for human presence in the long run if the project’s goals include culture, governance, and the human experience of living on another world. If the objective is cheap mass production or continuous industrial operations, robot colonies are superior in many ways. If the objective is a thriving, pluralistic human civilization off-Earth, robots will be indispensable enablers but not sufficient on their own.

In short, the three visions — rapid private Mars settlement, orbital industrialization at scale, and a rules-based lunar/cislunar ecosystem — are all plausible, overlapping routes for humanity’s push into space. Robot-first approaches are not only under active consideration; they are likely to be the workhorses that make any human future in space affordable and sustainable. The policy and ethical choices we make today about governance, equitable access, and the role of automation will determine whether those futures are broadly beneficial or concentrated and contested.

[End]

Filed under: Uncategorized |

Hi Jim,

I’ll take some time to write my vision of our future in space. I see people on Mars in a permanent settlement as a distant future possibility but with serious challenges. LEO dwellings and factories are feasible, but will take some time to obtain the necessary permissions and financing.

Space is slowly becoming more accessible. How should we use it?

Hi, Harry. Your “Mars One: Exciting Adventure or Hoax?” (8 A pr 2013), has had 51,878 views to date in ETC, more than double the closest competitor for all-time views. Doing a “keller mars” search in ETC brings up numerous other articles on Mars and similar topics. Your novel, Mars Rhapsody: A Story about the People, Technology, and Science of the First Mars Colony, captures a lot of your thoughts on space colonization. Thus, you have a rich background for pretty much any topic that’s related to space. Re an article idea, LEO (Low Earth Orbit) habitable structures (like Bezos’ O’Neill-style cylinders or something completely different?) sounds interesting. Taking any direction that interests you, though, might be the best way to go. -Jim

Hi Jim,

I am not a fan of those silly space cylinders. Maybe I’ll explain in a future column. -Harry

Dear Harry

This is Caltech alumni of 1963 Muvaffak İlhan GÖZAYDIN Since 1995 I have been involved with online learning . Lately I have been excited by AI and education .

AI is a wonderful soluti,on for converting courses from f2f to internet format . Plus many technical featured goods . Plus artificial teacher to follow up every students on personel basis . And his checking every move of the students Plus we need only we need a number of universities but good one . But I see no university adopted Aı CONVERTED TO ONLİNE COURSES İN THE usa WHY eVERY BODY İS AFRAİD OF ???

pLEASE COMMENT hARRY

bEST REGARDS